History

Massacres: The frontier violence that's hard to accept

Hundreds of massacres left thousands of Aboriginal people dead, a history many Australians struggle to accept. A brave few started documenting what happened.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

Selected statistics

- 65,180

- Number of Aboriginal Australians historians estimate were killed in Queensland from the 1820s until the early 1900s. [1]

-

97% - Percentage of of people killed in the massacres who were Aboriginal men, women and children. [2]

- 500

- Estimated number of massacres by settlers of Aboriginal people in Australia. [3]

- <10

- Estimated number of massacres by Aboriginal people of settlers in Australia. [3]

- 20

- Number of "very small, physical memorials to Aboriginal massacre sites across Australia". [3]

- 9

- Number of known cases of deliberate poisoning of flour given to Aboriginal people. [4]

- 25:1

- Ratio at which Aboriginal people of the Northern Territory were killed compared to white settlers from 1870s to 1900. [5]

- 12:1

- Ratio at which Aboriginal people of Victoria were killed compared to white settlers from the 1800s. [5]

- 44:1

- Ratio suggested by collaborative academic research. [1]

- 1794

- Year in which mass killings were first carried out in Australia. [4]

- 1928

- Year in which massacres are thought to have ceased. [2]

- 27

- Average number of Aboriginal people killed in massacres in NSW and Victoria between 1834 and 1859. [4]

- 34

- Average number of Aboriginal people killed in massacres in Queensland between 1859 and 1915. [4]

Massacres: The horrors of frontier violence

Any invasion of a country with an existing indigenous population seems to be inevitably linked with a long list of massacres on its indigenous peoples, and Australia is no exception. Almost all Aboriginal nations experienced massacres, [6] and nearly every Aboriginal community has a massacre story. [7]

Definition: Massacre

What is a 'massacre'? According to historians, a massacre is the "indiscriminate killing of six or more undefended people" over a limited period of time and with careful planning. [3]

Academics say the massacres of Aboriginal people were conducted in secrecy and very few perpetrators were brought to justice (the Myall Creek massacre is a notable exception). And they were planned in advance, "designed to eradicate the opposition". [6]

The number of Aboriginal people killed in retaliation of European deaths are off the scale. Among the most shocking is the Jack Smith massacre (Warrigal Creek, Victoria) in 1843, where about 150–170 Brataualang people were killed over 5 days in retaliation for the killing of one single person—Ronald Macalister, the nephew of a local squatter. [6] It's an atrocity which historians found fitting the criteria of ‘genocidal massacre.’ [3]

Aboriginal people had little chance of surviving. Their spears, clubs and hatchets had to fight swords, pistols, muskets, double-barrelled shotguns, rifles, carbines and bayonets, among other items.

The survivors were often used as slaves.

Research of Guardian Australia and the University of Newcastle found that some of the most violent episodes in Australia's colonial past took place well into the 1920s, in the Northern Territory and Western Australia. In some cases, Aboriginal people were forced to collect wood for their own pyres. [2]

The research also found that government forces, including soldiers, police, magistrates and native police, were involved in more than half of all massacres recorded between the 1820s and the 1930s. Massacres became more violent, systematic and calculated over time.

The death of a civilian was the most common trigger for a massacre, followed by "opportunity" attacks. The majority of massacres was planned with government involvement or sanction. "There’s always police involved in the story, right across Australia," knows Prof Lyndall Ryan, who led the University of Newcastle research team. [2]

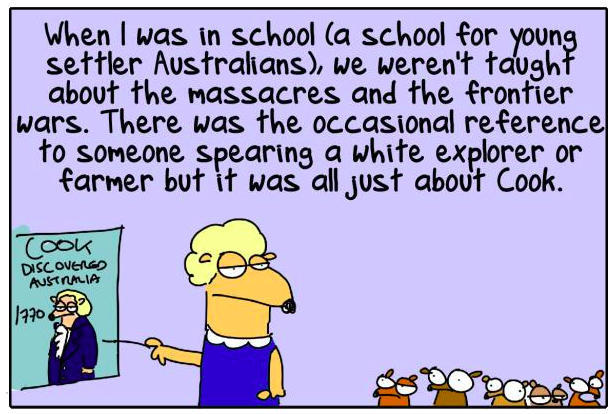

Accepting history

Australians are slowly coming to terms with their history of massacres. Many perpetrators kept silent for decades fearing arrest or retribution. Aboriginal survivors feared they'd be killed as well if they spoke. It seems this is part of "The Great Australian Silence" in our history.

But since the Uluru Statement of the Heart, and many individuals, called for more truth-telling in Australia the attitude towards this dark history is shifting.

"We so don't talk about that [massacre history] here in this country, but it's a real shared history that a lot of people don't know about," explains former AFL star Adam Goodes. "If we want to reconcile as a nation we have to understand where we came from and how we got to where we are today." [8]

No wild beast of the forest was ever hunted down with such unsparing perseverance as they [Aboriginal people] are. Men, women and children are shot whenever they can be met.

— Henry Meyrick, squatter, in a letter to his family in England in 1846 [4]

The whites appear to have acted with great moderation.

— Magistrate comment on hearing that William Carter had killed an Aboriginal family, including a pregnant woman and her unborn child at Mt Bryan, South Australia, in 1844. [2]

Why did the massacres happen?

Settlers killed Aboriginal people for many reasons [5]:

- Reprisals for murder. After Aboriginal people attacked European people, search parties retaliated ferociously.

- Theft. Massacres in reprisal for the killing or theft of horses, livestock or property are second only to reprisals for murder of a settler. [4]

- Struggle for land. Stockmen often led cattle to graze well beyond the limits of a station as areas needed time to recover.

- Lack of communication. Because the colonists didn't speak Aboriginal languages, and very few tried, they couldn't learn about Aboriginal people's culture or settle disputes.

- No reason. Sometimes colonists attacked for no rational reason. It could just be that the opportunity arose, or the cheekiness of the person, e.g. for being "found standing in the moonlight in the doorway of [a squatter's] hut". [5]

- Fear of attacks. The invaders were afraid that Aboriginal people who were painted for important ceremonies were in fact performing war dances and would later attack.

- Sexual gratification. Initially there was an over-population of male Europeans. Some sought to remove all Aboriginal males so that they could sexually abuse their women and girls.

White settlers often found no reason to spare Aboriginal men and boys. Aboriginal girls and women, however, were often kept for sexual pleasure. Research uncovered "stories of girls as young as eight who were kidnapped and raped and infected with syphilis. Teenage girls were kept for sex and chained up at night to stop them running away. One group of girls was held in a chicken wire enclosure". [5]

No wonder that Aboriginal people refer to massacre sites as "taboo site[s] of trauma". [3]

The legacy of massacres still impacts Aboriginal people today. With missing parts of family trees due to massacres many don't know who they are or where they're from. [3]

There’s certain roads people won’t drive along. It’s not just felt by Aboriginal people but by non-Aboriginal people as well.

— Aleshia Lonsdale, Wiradjuri artist [3]

It's not history that you necessarily want to embrace but it's a really important chance between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people for truth telling.

— Steve Kinnane, Miriuwung man and First Nations researcher [10]

Story: Black massacre memories

"My mother would sit and cry and tell me this; they buried our babies in the ground with only their heads above the ground. All in a row they were. Then they had tests to see who could kick the babies' head off the furthest. One man clubbed a baby's head off from horseback.

They then spent the rest of the day raping the women, most of whom were then tortured to death by sticking sharp things like spears up their vaginas till they died.

They tied the men's hands behind their backs, then cut off their penis and testicles and watched them run around screaming until they died. They killed in other bad ways too." [11]

Story: They carried their ticket to die

In 1924, according to oral history passed down by survivors, a group of Gija and Worla men were convicted of killing a bullock at Bedford Downs station (southern Kimberley region, WA).

They were sent back to the station with “tickets” around their necks as a label of their guilt. Some removed the tickets before they reached the station, others left them on.

When they arrived, those who still had their tickets on were sent to a remote area to chop wood. After spending the morning chopping wood, they were given food poisoned with strychnine, causing them to die painfully. Their bodies were then burned.

Two men who refused to eat escaped. They, along with two women who had also witnessed the killings, passed on this story. [2]

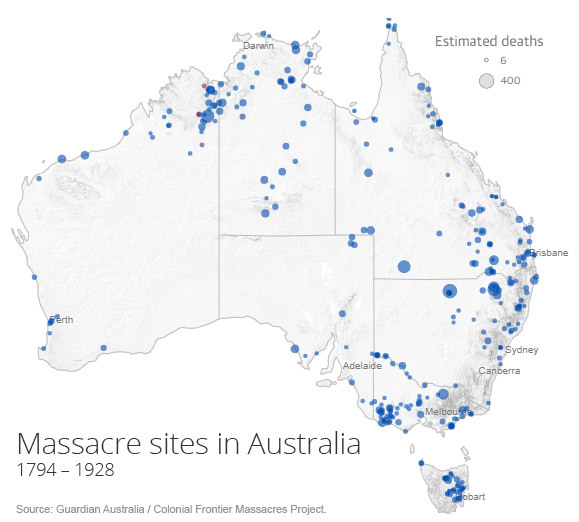

Where did the massacres occur?

There are hundreds of sites all over Australia, but finding them usually takes a lot of detective work. Massacres might have been mentioned in the media only in passing, by the boisterous perpetrators in the pub, or not at all. Researchers rely on settler diaries, newspaper reports, and Aboriginal evidence to create a list.

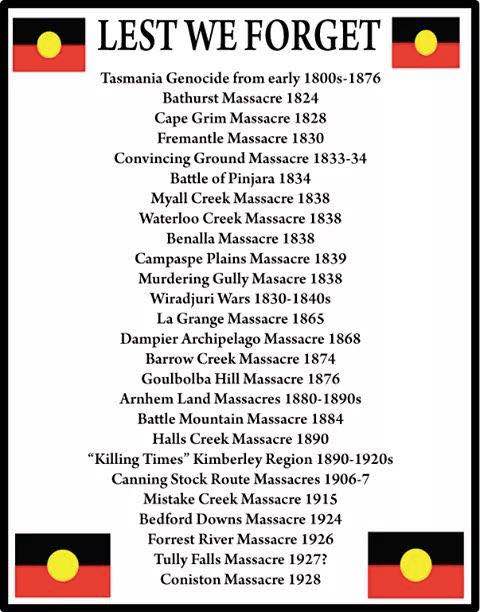

The University of Newcastle's online mapping project aims to document as many massacres as possible, compiling settler diaries, testimonies from survivors, and newspaper articles from the time. After 4 years, in July 2017, it had captured 150 massacres resulting in at least 6,000 deaths, [6] reflecting how difficult it is to find and verify each incident. By the end of 2021, the number of massacres had more than doubled to 311. [10]

By the time the project is completed researches expect to find that nearly 15,000 people were killed in massacres (defined as where 6 people or more died). This doesn't include smaller attacks, which have been estimated by some academics to bring the death toll to more than 30,000 from 1788 until the 1940s. [6]

Some better known massacre sites include Myall Creek, Waterloo Creek, Coniston, Appin, Bluff Rock, Slaughterhouse Creek, Pinjarra and Woodford Bay.

A 1914 letter to the editor of the Northern Star, a newspaper published on the NSW north coast, gives you some insight into what was going on: [12]

"Besides the Myall Creek massacre there were other and greater massacres perpetrated … for trivial offences, and sometimes for no substantial reason at all. The whites had a method of seeking retribution that was a disgrace to Christianity – that of punishing a tribe, probably an innocent one, for the crime of an individual. The whites, far from showing any regard for the lives of the original owners of the country, ignored all their rights as to property, and yet were most brutal when their own rights were transgressed."

Today massacre sites are on private land, or mining properties; others are at the bottom of reservoirs, because so many of the massacres happened at campsites close to creeks. [3]

Australia's place names are also giveaway evidence of frontier massacres: Murderers Flat, Massacre Inlet, Murdering Gully, Haunted Creek, Slaughterhouse Gully, Niggers Bounce.

When I visit Aboriginal communities today the first thing they do is take you to the massacre site.

— Prof Lyndall Ryan, historian, University of Newcastle [6]

For a comprehensive listing of massacre sites check out the Australian Frontier Conflicts website and Colonial Frontier Massacres in Eastern Australia, a research project of the University of Newcastle. Culture Victoria offers a map with massacre locations between 1836 and 1853.

Aboriginal people killing Aboriginal people

Most people associate massacres in Australia with Europeans killing Aboriginal people. But there were also instances where Aboriginal people killed other Aboriginal people, for example Native Mounted Police.

Queensland's Native Mounted Police operated from the late 1840s until about 1904. It was Australia's longest-running Native Police. [13] White officers commanded groups of about six or seven Aboriginal trackers. The goal was simple: to move Aboriginal people off the land the European colonists wanted, often by force and often violently, and to protect and support the settlers.

There's only one reason that the Native Police were there — to kill Aboriginal people and to facilitate the theft of land.

— Bryce Barker, archaeologist and chief investigator on a Native Police research project [13]

Historians estimate that Queensland's Native Mounted Police was responsible for the deaths of between 24,000 and 41,000 Aboriginal people. [13]

While acting under the command of white superiors, most of the men responsible for these massacres where Aboriginal. [13] They were hired from areas far away from the regions where the killings occurred to avoid that they were related to their victims, and to prevent them from running away.

Some young Aboriginal men volunteered to join, possibly to survive or after losing their family and land to the advancing invasion.

Today the descendants of Aboriginal trackers and troopers wrestle with this past. "It's very heartbreaking," offers Yulluna woman Hazel Sullivan whose grandfather organised killings. "It's like having a murderer in your family." [13]

But rather than feeling ashamed and angry, most agree that their priority is for Australians to properly acknowledge the history of Queensland's Native Police and its brutal impact on Aboriginal people – a truth-telling, which is one of the key messages of the Uluru Statement From the Heart.

Finding evidence of these murders is difficult as Aboriginal people often disposed of the bodies with traditional burial rituals and not mass graves. But one piece of physical evidence of the Native Mounted Police is their camp sites.

"What we soon realised was [that] Queensland native police set up base camps all over Queensland," says Professor Bryce Barker, an archaeological anthropologist from the University of Southern Queensland, and one of the leaders of a research project investigating the evidence of Native Mounted Police life. "Looking at the record, we were able to establish that there were over 200 of these [camp sites] established at various times across Queensland." [7]

The Police occupied sites for as long as the conflict took to suppress – some for just a few months, a few for a period of more than 20 years. Archaeologists found items such as bullets from government-issued guns or uniform buttons, proving the existence of Native Mounted Police camps. [7]

Writing books and talking about it would be a good healing process for Australia.

— Vince Harrigan, traditional custodian, Balnggarrawarra people [13]

The Waterloo massacre

The Waterloo massacre occurred 50 kilometres south-west of Moree (380 kilometres south-west of Brisbane), on Waterloo Creek (what is known today as Millie Creek [14]) on Australia Day (26 January) 1838, a few months before the massacre at Myall Creek.

NSW policeman Major James Nunn and around 30 mounted soldiers and stockmen combed the Gwydir region on an expedition to suppress Aboriginal people.

They committed a series of atrocities in the area, but the Waterloo Creek massacre was the most savage.

Five white men were killed, but between 120 and 300 Aboriginal people of the Kamilaroi nation were shot by Major Nunn [15], making it the maybe the largest single massacre in Australia.

The exact details will never be known as there are no official records and only unreliable accounts from the perpetrators who were scared of prosecution after the murderers of Myall Creek were punished.

The Kamilaroi community in Moree officially commemorates the anniversary of the massacre since 2013. [16]

The Coniston Massacre

The Coniston Massacre happened in 1928 at Baxters Well, about 200 kilometres north of Alice Springs in the Northern Territory, after the murder of dingo scalper Frederick Brookes at Yurrkuru (formerly known as Coniston Station or Brooks Creek) [17].

Brookes was killed by an Aboriginal man named Bullfrog (traditional name Japanangka), who it is believed was angry that his wife was staying with Brookes.

Constable George Murray led reprisal parties against Aboriginal people over a wide area between August and October 1928. During attacks more than 30 Aboriginal people were killed, but unofficial estimates, for example by the the National Museum of Australia, put the number at more than 60, and Aboriginal people estimate 170 were killed. [4]

Many more Aboriginal people fled the area, never to return. Bullfrog hid in a cave and was never captured by Murray's party [17].

80 years later a memorial commemorates the massacre, built by Aboriginal volunteers. The Coniston massacre is often referred to as Australia's last state-sanctioned mass killing.

In August 2018, NT Police Commissioner Reece Kershaw laid at wreath and apologised for what happened. "There was no excuse or justification for what occurred here 90 years ago," he said in a speech at Yurrkuru. "As a police officer and commissioner I'm sorry for what has occurred." [18]

We're not bitter. We just want everybody to know and to acknowledge this black spot in Australian history. This is what they call hallowed ground, like Gallipoli is for white fellas.

— Geoff Shaw, Kaytetye man, during the opening of the memorial [17]

Tasmania's Black War

As the Tasmanian colony expanded on Aboriginal people’s homelands, the horrifically violent Black War broke out between 1824 and 1831 in the eastern part of the island. Self-appointed parties tracked Aboriginal people’s campfires and ambushed them, murdering as many as possible. White settlers were attacked and brutally killed, too, their homes raided and burnt, sheep and cattle speared. [19]

The war claimed the lives of 223 colonists, but as historian Nicholas Clements writes in his 2014 book, The Black War, it "annihilated" the Aboriginal population. He believes 60% of the First Nations people in the war zone lost their lives. "Nowhere else in Australia did so much frontier violence occur in such a small area over such a short period," he writes.

Eventually, the eastern Tasmanian survivors of the colony’s violence and introduced illness – fewer than 100 – were resettled on Flinders Island, off Tasmania’s north-east coast. But losing their country broke the heart of many and they rapidly died in the years following.

Origin of the term 'genocide'

Tasmaniann Nuenonne woman Truganini was long considered as "the last of her race" and came to be used as a case study by Raphaël Lemkin who coined the term 'genocide' in 1944.

To that end, the Tasmanian Black War contributed to the creation of the term, and the UN conventions against it. [19]

Calling for information on Pilbara massacres

The Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre in South Hedland seeks information, stories or recollections about Pilbara massacres.

Please contact the centre on (08) 9172 2344.