History

Australia has a history of Aboriginal slavery

Australia's slavery started because other countries abolished it. Aboriginal people were blackbirded and used in the pearling, sugar cane and cattle industries. They suffered terrible abuse and were denied their wages.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

Was there ever Aboriginal slavery in Australia?

Slavery is never a convenient topic. We easily associate countries like Africa and America with slavery, but Australia?

What is slavery?

If you read it up in the dictionaries, slavery is “the condition in which one person is owned as property by another” and the owner has "absolute power” over their "life, liberty, and fortune”. Such people are usually forced into work "in harsh conditions for low pay”. [1]

Australia’s slaves worked in all essential industries, from the 1840s through to the 1970s: [2][3]

- The first slaves to reach Australia from the South Sea were used as shepherds on properties in southern New South Wales, but died from the cold.

- When the American Civil War cut off the world's cotton supply, Australian slaves were used to establish cotton plantations in southern Queensland. A strong male would cost the modern equivalent of between $5 and $19, while women, particularly Tahitians, who were regarded as the most attractive, often fetched $32.

- Between 1842 and 1904 more than 60,000 men and boys from the South Pacific islands, and an unknown number of women and girls, were kidnapped and brought to Australia to work as slaves on the sugar plantations that still dot the country's north-east coast. Many were also forced to work as pearl divers in the north.

- Between the 1860s and the 1970s, Aboriginal people of all ages were taken from their homes and sent to work on cattle and sheep properties all across Australia. Several such schemes were run by colonial and state governments, theoretically to protect Aboriginal Australians from mistreatment.

And mistreatment was rife. Queensland government files and personal reports show that from the 1880s, and for at least 40 years, there were no limits on how many hours Aboriginal people worked, how hard their labour was, how bad their treatment or the provision of food and living quarters.

Reverend John Gribble, a keen observer of injustice in the 1880s, noted (my emphasis):

"I have seen numbers of natives brought in from the interior, and some of them had never before seen the face of a white man, and they were compelled to put their hand to a pen and make a cross which they never could understand, and having done this they were then slaves for life, or as long as they were good for pearl diving." [4]

Minimum conditions, introduced in 1919, were wildly ignored in the absence of any inspections. [5]

[Shelter for many Aboriginal workers was] worse than they would provide for their pet horse, motor-car or prize cattle.

— Chief Protector of Aborigines, Queensland, 1921 [5]

Low pay or no pay

The definition of slavery mentions 'low pay', and this was very true for Aboriginal slaves.

In the early 1900s in Queensland, despite regarded as more reliable than superior white stock riders, Aboriginal workers received only about 3% of the white wage rate. [5]

At the same time in Western Australia, recommendations for a minimum 5 shilling monthly wage were successfully opposed by pastoralists, leading one parliamentarian to describe the system as "another name for slavery". [6]

From 1919 the government claimed pastoral workers would get 66% of the white wage, but records show that in 1949 workers got only 31%. [3] In fact, Aboriginal people would never get the 66%. Every year between 1941 and 1956 the government sold Aboriginal labour for less than that. [3]

Whatever little money Aboriginal workers were able to save governments were keen to get their hands on. Evidence shows it intercepted federally-paid maternity allowances from 1912 and child endowments from 1941, and paid only a fraction through to the mothers. [3]Tens of millions of dollars were taken out of the Queensland trusts and never returned to Aboriginal workers. The 'stolen wages' is now a national problem governments try to sit out. Claimants need a lot of patience or die waiting, and compensation has been insufficient, bordering on insulting for a lifetime of work.

"When I got the first $4,000 [of a total of $7,000] I was told I had to sign a paper that I would not take the government to court and I signed because I thought it was better than nothing,' says Felicity Holt, a 77-year-old claimant from Queensland. [3] "I found out I couldn't get the money unless I signed the document." Stolen wages is, however, not just about the money. In the 2006 Stolen Wages report numerous statements by Aboriginal people described the conditions in which they had lived and worked in terms evoking the notion of slavery. In fact, until at least the 1950s, if not later, these conditions satisfy the legal definition of ‘slavery’ existing under Australian and international law at the time.[7]

[Slavery is] an elephant in the drawing-room of civilised debate.

— Stephen Gray [7]

While Aboriginal people have no difficulty thinking of their past treatment as slavery, many non-Aboriginal people – including judges and lawyers – find the notion of slavery in an Australian context confronting. [7] Worse, some prime ministers of Australia believe that there was no slavery in Australia. [8]

A look into history might bring clarity.

History of Aboriginal slavery

Interestingly, Australia's slavery started because other countries abolished it.

Britain wanted cheaper cotton, but the world’s cotton market had been thrown into turmoil because the UK abolished slavery in 1833 and mass slavery ended in the United States after the Civil War in 1865. But this didn't stop the British from accepting it elsewhere. [9]

Starting in the 1860s, slavery and the Aboriginal labour debate were clearly linked. Religious and humanitarian organisations used 'chattel bondage' and 'slavery’ to describe north Australian conditions for Aboriginal labour, [7] and the word was regularly used by journalists and human rights activists for another 100 years, until the 1960s.

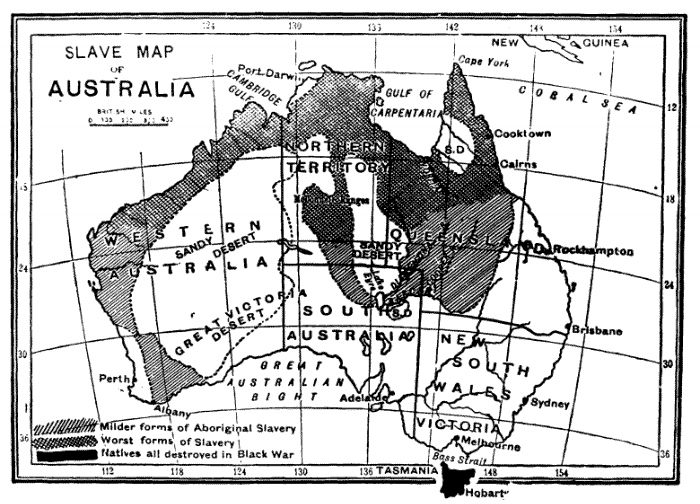

Writer Arthur James Vogan, in his 1890 novel The Black Police: A Story of Modern Australia, included a ‘Slave Map of Modern Australia’ towards the end of the novel. It was reprinted in the September-October 1891 edition of the British Anti-Slavery Reporter. It showed most of central and north Queensland, the Northern Territory and coastal Western Australia as areas where “the traffic in Aboriginal labour, both children and adults, had descended into slavery conditions”. [7]

Vogan identified the "worst forms of slavery" in Australia's north, and in 1932 the North Australian Workers’ Union still found the same words when it noted that "[a] slave owner would not allow his slave to be decimated by preventable disease and starvation the same as these people are in the country or bush. If there is no slavery in the British Empire then the NT is not part of the British Empire; for it certainly exists here in its worst form." [7]

Slave owners controlled all aspects of Aboriginal lives, including movement, place of residence, family life, finances and sometimes even sexual relations (see section further below for details). Aboriginal workers were denied access to any bargaining process, freedom of movement or the right to refuse to work.

Aboriginal slaves helped not only in the cotton industry, but also run the sheep and cattle stations in northern Australia, and their owners were "heavily in debt to the Aboriginal, as well as other Australians". [7]

How a Scot shocked Australia

In 1904, reports emerged of cruelty and mistreatment, particularly on remote pastoral stations in the north-west of Western Australia. One vocal voice was Walter Malcomson, a journalist who had lived for seven years in the North West of Western Australia [10] before migrating to Belfast in Northern Ireland. In April 1904 he sent a letter to the editor of The Times of London, condemning the continued "cruel and inhuman treatment of the aboriginal slaves" in the "slave state" of Western Australia. [11]

"The original owners of the soil—the aborigines—having been robbed of their birthright—the land—are now 'indentured', 'assigned', bound by 'contract' or 'agreement'—call it which you choose, it spells slavery every time," he wrote empathetically. His accusations caused widespread denial of the Australian authorities and "sensational shock" in the public. [12]

William Harris, a well-educated Aboriginal man who had worked with pearlers and squatters (and probably also as a tracker) had read Malcolmson's letter and the comments in the newspapers. In an interview with the Sunday Times of Perth he said with reference to Malcolmson: "From my own experience of the Nor'-West squatters and the blacks [I] can say his statements are absolutely justified. If they have any fault it is that they don't go far enough." And later: "[Aboriginal people] have been so mercilessly despised and oppressed by their white owners and rulers that their feeling towards the whites is that of an enslaved people." [13] The whole statement makes worthwhile, albeit shocking, reading.

A Royal Commission confirms slavery

Following the reports, Dr Walter Edmund Roth, who had been the Chief Protector of the Aborigines in Queensland, was called to Western Australia in August 1904 to work for the Royal Commission on the Condition of the Natives which investigated the treatment of Aboriginal people in the state. [14]

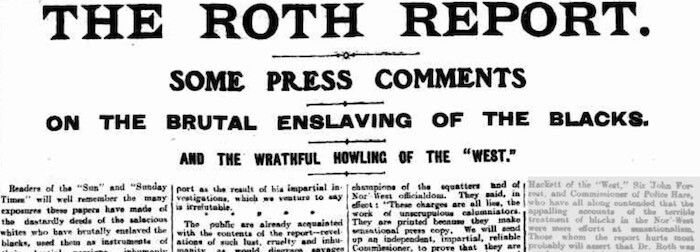

Roth published his findings, commonly known as the Roth Report, in late January 1905. [15] It was hotly discussed in the Australian press and even in Parliament in London. He reported that Aboriginal people lived in poor conditions, prisoners were maltreated, and that there were considerable irregularities when distributing government rations.

Newspaper headlines at the time clearly referred to these practices as slavery: "Slavery in Australia", [16] "Slavery in the West" [17] and "The Roth Report – Some Press Comments On The Brutal Enslaving Of The Blacks". [18]

The word 'slavery' reverberated through the Australian press for years to come. Here is an extract from a front page article in the Western Australian Sunday Times in December 1909:

"Slavery in Kimberley – Aborigines Exploited by Absentees. The following trenchant re-statement of the aborigines [sic] slavery in the North-West and Kimberley comes from a correspondent at Derby. As the writer has been in that part of the country for five or six years, it is palpable he knows what he is writing about, and someday (perhaps!) the Government will acquire enough courage to put a stop to the absolute unmitigated, cruel slavery which is rampant throughout the Black North. [...] All throughout East and West Kimberley a system of abject slavery exists. Men, women and children are forced to work as slaves through being the victims of circumstances."[19]

The legalised slavery called the "indenture system" [means] the hunting of men like wild beasts, the barbarous flogging of the slaves, the chaining of untried prisoners, and the brutal lust which respects not mother nor wife nor daughter.

— William Harris, Aboriginal worker [13]

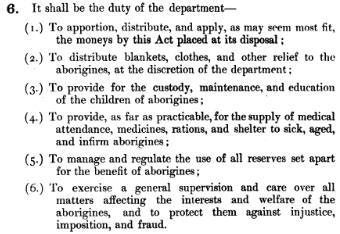

Legislation in almost every state and territory facilitated the enslavement of Aboriginal people by prescribing every aspect of their lives, in some cases for almost 60 years: The Aborigines Act 1905 (Western Australia), the South Australian Aborigines Act 1911 and the Aboriginals Ordinance 1918 (Cth) are examples.

Officials were not shy to use the slavery analogy to promote legislation to other states despite the fact that some of them were aware that Australia was in breach of its obligations under the 1926 Slavery Convention. [20][21]

By 1943 the value of Aboriginal slave labour in Western Australia was estimated to be £60,000 a year, [7] about A$ 4 million in today's dollars. Not that Aboriginal people would see much of it. Their wages were non-existent or discriminatory, a practice only declared unacceptable in the Northern Territory cattle industry in the Equal Wages decision in 1966.

Penelope Hetherington documents this exploitation of both European and Aboriginal children in her book Settlers, Servants and Slaves.

Basically the land was stolen off them and if they wanted to stay on their land, and have that connection to country and that connection to spirit, they actually had to work for free for the person who stole it.

— Warwick Thornton, Aboriginal director [22]

Employers had almost total control

Not all Aboriginal workers were treated like slaves, but employers had a high degree of control over ‘their’ Aboriginal workers:

- in some cases they were bought and sold as a personal possession (particularly where they ‘went with’ the property upon sale)

- they had a restricted freedom of choice and movement, irrespective of any lack of consent

- they were subjected to threats and force

- they were in fear of all forms of violence

- many were treated cruelly and abused

- their sexuality was controlled

- their labour was forced

The fact that the law actually authorised many of the pastoralists’ actions, and that it could in general be relied on to turn a blind eye to formal illegalities, meant that employers exercised a form of ‘legal coercion’ over their workers in a manner consistent with the legal interpretation of slavery. [7]

The understanding of what constitutes 'slavery' is not consistent through time—neither in popular opinion nor in academic works. But several comments used the word to describe what happened to Aboriginal people: [7][24]

- Reverend John Gribble observed as early as 1878 how white men removed children from their Aboriginal mothers to use them as labourers. "I have seen hundreds of children brought into Cossack [a WA town about 1,500 kms north of Perth] who have been torn away from their mothers, and yet it is said that where the British flag flies slavery cannot exist." [4]

- In 1927, in a comment quoted in the Stolen Wages report, the Northern Territory Chief Protector Herbert Basedow said that pastoral workers "are kept in a servitude that is nothing short of slavery".

- In 1930, the Minister for Home Affairs, Arthur Blakely, wrote of the Northern Territory pastoral industry that "it would appear that there was a form of slavery in operation and that aboriginals [sic] were being worked without any remuneration whatsoever".

- In 1974, in his film The Unlucky Australians, John Goldschmidt explains how "the authorities made [Aboriginal work] slave labour by making the Aborigines wards of the state", referring to the Welfare Ordinance of 1953 which made Aboriginal people of the NT wards and the Director of Welfare their guardian. As wards, Aboriginal workers couldn't leave the station where they were working, "could be forcibly brought back with chains around their necks". [24]

It's futile to look to the courts for decisions about slavery – there are none – because, as some opine, courts are made "to bring disputes between parties about certain kinds of issues to an end in an acceptable way" [7] and not admit that the treatment of Aboriginal people amounted to slavery.

Nonetheless, there is strong legal support backed by historical evidence for a finding that slavery existed in Australia. [7]

Aboriginal slavery disguised as 'Protectionism'

Between the 1860s and the 1970s, Aboriginal people of all ages were taken from their homes and sent to work on cattle and sheep properties, in kitchens, homesteads, shearing sheds or on the land, all across Australia.

Several such schemes were run by colonial and state governments, theoretically to protect Aboriginal people from mistreatment. Like station owners, the laws gave the governments an extraordinary level of control over every aspect of Aboriginal people's lives, including their personal finances, where they lived, where they worked and how much they were paid.

But Historians Dr Rosalind Kidd and Dr Thalia Anthony have documented how Aboriginal people of all ages were forcibly sent to work [6], sometimes far from their homes, in often horrific conditions. [5]

Laws in Western Australia in 1874 allowed Aboriginal children to be sent to work from the age of 12, and an even lower age from 1886. [3] They endured 16-hour days, floggings and forced removal from families.[25] Boys were generally sent to work on pastoral properties, while girls worked as domestic servants. They were exposed to both physical and sexual abuse.

Aboriginal children of mixed descent were sent to missions all over Australia where they were often forced to labour, and educated as domestic servants or labourers for non-Aboriginal people who frequently abused them in many ways.

"I did the washing, cooking, ironing," remembers Felicity Holt, now well over 75 years old, but back then 16 and hoping for a future in nursing. "I was getting up at 5 am to milk the cows and had to separate the milk from the cream. Then I had to cook breakfast, get the kids ready for school, make lunches for the kids, cook the evening meal and prepare things for the following day. By the time I got to bed it was 10 o'clock at night. It was like slave labour." [3]

They were either unpaid or received only a few shillings pocket money. State governments assured these workers that their wages were placed in a government trust, but most never saw a cent. Aboriginal people have been trying to recuperate these stolen wages for years. But governments delay, waiting for claimants to die. If they do pay compensation for 30 or 40 years of work it's often a token gesture only--or pocket money all over again.

According to Dr Kidd, some police colluded with business owners to increase prices on goods, to forge witness signatures to withdraw workers' money or to deny them access to their money. [3]

Some never lived to see the end of the schemes in 1970.

'Blackbirding' of South Sea Islanders

As fewer and fewer convict labourers were available in Queensland, a preferred method of 'recruitment' between the 1860s and 1904 was blackbirding. This involved white ships arriving on an island during the daytime to discuss trade, leaving peacefully, then returning at night dressed in all black to take people by force who would then be used as slaves on Australian sugar plantations. [9]

Numerous decoys were used: lure islanders with trinkets, entice trusting and curious people into the ship’s cargo hold, pose as missionaries only to reveal their guns during assembly, or give tribal leaders guns, alcohol or other goods in exchange for a few prisoners of rival tribes.[2][9] Many died during the 4-month journey to Australia.

Definition: Blackbirding

The term may have been formed directly as a contraction of 'blackbird catching'. 'Blackbird' was a slang term for the local South Pacific indigenous people. It might also have derived from an earlier phrase, 'blackbird shooting', which referred to recreational hunting of Aboriginal people by early European settlers. [25]

About 62,000 South Sea Islanders (or 'Kanakas' as there were colloquially known) were shipped to Australia from 80 Pacific islands across what is now Vanuatu, New Caledonia and the Solomon Islands, but records remain poor as many were destroyed by land holders. [26]

Once in Australia, they were sold to plantation owners. A strong male would cost the equivalent of between A$5 and A$19 while women, particularly Tahitians, fetched around A$32. [25]

The official name of the blackbirded slaves was 'indentured labourers', a term used to "soften" the reality of what happened. Today we would replace it with 'contractors'.

Faith Bandler, famous for her relentless campaigning for the rights of Aboriginal Australians and South Sea Islanders, is the daughter of a blackbirded slave. Bandler's father, Wacvie Mussingkon, was kidnaped in 1883 at age 13 from the island of Ambrym in what is now Vanuatu. He escaped in 1897. [2]

The life of a slave on an Australian sugar plantation was little different from that on the American cotton plantations. Brutality and deprivation were the daily ritual, Bandler says. Wages were low and conditions harsh. The work was hard, brutally hot – cane was burned to ease its harvest – and regularly dangerous. [27]

It appears the South Sea Islander slaves were sometimes buried in mass graves, one of which was discovered in Queensland in 2012. Hidden under an old cane plantation outside Bundaberg, beyond weeping fig trees, the bodies of 29 South Sea Islanders were buried in what is believed to be the first confirmed mass grave on an old sugar plantation. [26]

Members of cane farming families are still reluctant to admit that graves exist on their properties, yet graves are a crucial piece of evidence consistent with slavery, and there was evidence to suggest Islanders working in the cane fields were often buried "where they fell", or executed for minor crimes. [26]

When slavery was outlawed in 1901, unions banned Pacific Islanders from working on farms and many were simply deported. [25] Those who stayed were denied welfare and citizenship. 15,000 to 20,000 descendants of the 'sugar slaves' are now living in Australia, mainly along the Queensland coast, but mostly unrecognised and without equal opportunities. [2]

The Commonwealth recognised Australian South Sea Islanders as a distinct cultural group in 1994, followed by the Queensland government in 2000 and the NSW government in 2013. [27]

Two of north Queensland’s major cities – Mackay and Townsville – are named after men who participated in the blackbirding trade: John Mackay and Robert Towns.

Slavery in the pearling industry

Australia's pearling industry flourished between the 1850s and 1950s.

Pearling began in earnest at Shark Bay, Western Australia, in the 1850s and in the Torres Strait in 1868 with 16 pearling firms operating on Thursday Island in 1877. By 1910, nearly 400 luggers and more than 3,500 people were fishing for shell in waters around Broome, then the biggest pearling centre in the world. [28] Historians estimate that around 1,000 Asians were captured and sold into slavery. [25]

Aboriginal people were rounded up from pastoral stations and sold for around 5 pounds (around A$550 today). Pregnant Aboriginal women were particularly prized because their lungs were believed to have greater air capacity. [25]

From 1862-68 to the turn of the century, Aboriginal people in Shark Bay worked without wages collecting shell found on beaches and low tidal flats (also called 'dry shelling' or beachcombing).

Within three years, this supply was so exhausted that larger boats were sent out two kilometres off shore to collect oysters in deep water. 6 to 8 Aboriginal men and women in a boat would dive down naked for shell, i.e. they dived down deep with no oxygen, no snorkel and no mask. [28]

Pearl divers regularly faced several potentially fatal risks: shark attacks, colds, influenza, pneumonia and decompression sickness ('the bends'), but also nutritional deficiency. Some sources estimate the fatality rate for divers at 50%. [28] The Aboriginal cemetery in Broome is an almost forgotten place of this history.

Cyclones were another threat that could wreak entire fleets. Between 1908 and 1935, four cyclones hit the pearling fleet at sea. Around 100 boats were destroyed and 300 men were killed. [28]

Story: Seaman Dan

Between 1946 and 1963 Torres Strait Islander Henry Gibson, aka Seaman Dan, spent many years at sea as a pearl diver and boat captain. At the time pearling was a huge industry throughout Northern Australia but particularly on Seaman Dan's home of Thursday Island in the Torres Strait.

He also played music and sang whenever possible. His songs were influenced from jazz, blues, hula, reggae, dixie and traditional maritime music.

Music continued to be a hobby for Seaman Dan even after a case of the bends forced him out of the pearling industry. But a chance meeting with a visiting musicologist in 1999 changed his life. He was 'discovered' and began a new career as a recording and touring musician.

Australia – built from slave money?

A University College London study tracing the legacies of British slave-ownership has shown that Australia was partly built from slave money. [25]

Following the abolition of slavery, British slave owners received compensation from the British government for the loss of their 'property' (read: people sold into slavery). Many of them used the money to travel to Australia where they bought up large parcels of land, became directors of banks, museums and libraries, built churches and became Governors. [25]

In his book Black Pioneers Henry Reynolds tracks the role of Aboriginal people in the exploration and development of colonial Australia. He reveals that thousands of black men, women and children worked for the Europeans in a wide range of occupations: as interpreters, concubines, trackers, troopers, servants, nursemaids, labourers, stock workers and pearl-divers.

See also How Aboriginal people helped build Australia.

Was it legal to use Aboriginal people as slaves?

Before Australia introduced its own legislation to prohibit slavery (Criminal Code Amendment (Slavery and Sexual Servitude) Act 1999 (Cth)) it was contained in various British laws.[7]

The first of these was An Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, passed by the British Parliament in 1807, followed by further legislative measures in 1824, 1833 and 1843. Under section 10 of the Slave Trade Act 1824 (UK) it was an offence to "deal or trade in slaves or persons intended to be dealt with as slaves". [7]

Slavery was outlawed in the British Empire, including Australia, by 1833. [6] Unambiguous legislation consolidating these Acts of Parliament and prohibiting slavery was passed in 1873.

Australia also ratified the Slavery Convention in 1926 and again in 1953 when the Convention was amended. [6]

But even when the various local governments of Australia gradually made the importation of 'indentured servants' illegal, many blackbirders just continued on and rarely were brought to justice. [9]

However, any legal discussion of slavery must be based on the meaning of 'slavery' at the time the alleged acts of slavery occurred.

Could Aboriginal people sue the Australian government over slavery? Probably not. Court processes in both native title and Stolen Generations litigation have generally disappointed Aboriginal people, and so has litigation in stolen wages cases. [7]

When was slavery abolished in Australia?

Under pressure from the British anti-slavery movement, the newly formed Australian government banned slavery in 1901 and ordered islanders to be repatriated. But some ship captains decided to save the money, or the hassle, of the long trip, took their human cargoes well offshore and dumped them on islands or threw them overboard. [2]

And the end of slavery in Australia did not mean the end of discrimination against the islanders who remained. Unions banned them from working on European farms, the only work they were trained for, and the colour of their skin condemned them to the same racism that Aboriginal people experience.

Is there still slavery today?

Yes. Between 2004 and 2014, 235 people were referred to the Support for Trafficked People Program as victims of slavery. Slavery continues in Australia. The skin has changed but the snake is the same. It now looks like a girl forced into marriage at the age of 12; a hospitality worker who had her passport taken from her and is told that she must work 15-hour days to 'repay her debt'; or sex-trafficked women shackled to beds. [25]

Since 2019 Australia has a Modern Slavery Act, but has been criticised because the Act

- only applies to businesses with annual revenue of more than $100m;

- does not impose any penalties;

- does not compel businesses to prove there is no forced labour in their supply chains; and

- does not include an independent anti-slavery commissioner. [29]

Instead, the legislation relies on concerned consumers taking notice of reporting failures and making their buying decisions accordingly, thereby pressuring companies to take modern slavery risks more seriously – a very unlikely scenario.

On 1 January 2019 Australia enacted the Modern Slavery Act 2018 (Cth). Companies of a certain size must publish an annual "Modern Slavery Statement" that describes what actions they have taken to assess and address modern slavery risks. Prior to this Act Australia had no legislation that protected against slavery.

However, a 2021 analysis of the quality of 239 modern slavery disclosure statements from ASX 300 companies revealed that more than a third had poor disclosures that failed to meet the minimum reporting standard, indicating they didn’t understand the risks in their supply chains. [30]

Names link to the past

Some places in Australia offer a link to its past of slavery, often unrecognised by the locals who live there.

Benjamin 'Ben' Boyd, a Scottish immigrant and businessman, was involved with ship and whaling industries and sheep farming in the 1840s. He brought two boatloads of slaves from Melanesia in the Pacific who were unaware they had signed up for five-year contracts. When state laws changed and made these agreements invalid, Boyd abandoned the slaves and left them to their own devices. His demeanour was bad enough to trigger an inquiry from the Colonial Office in London. [31]

Yet his name lives on. Boydtown is a village near Eden, on the far south coast of New South Wales, with Ben Boyd National Park nearby. Boyds Tower Road leads to Boyds Tower, a former lighthouse. You can travel on Ben Boyd Drive in Eden, or Ben Boyd Road in Sydney.

Calls to remove Boyd's name are growing stronger, especially with the tailwind of the Black Lives Matter movement. [31]

Australia needs to own up to its slave history

Slavery is part of Australian history, as much as the shearer, the convict and the Anzac. We need to stop denying our own racist past and overcome the silence of Australia's historians who caused few Australians being aware of this brutal period of our history.

It seems to be a unique Australian problem.

You are not personally responsible for this history. But we are all responsible for how we remember our nation's past and how we might go about redressing its violence.

— Alecia Simmonds, Chancellor's Postdoctoral Research Fellow, University of Technology, Sydney [32]

Most North Americans are perfectly familiar with the fact that their country was built on the backs of slavery, that their wealth has its roots in slave labour and that this history can help to explain why African-Americans still experience discrimination today. [25]

Australians, on the other hand, are blissfully ignorant until they're forced to confront it, at which point, they ask that it not be mentioned again. The same applies to any other uneasy chapter of Aboriginal history.

"The vast majority of non-Indigenous Australians have no idea of the enormous debt they owe to the Aboriginal men, women and children whose labour built this country," says historian and author Dr Rosalind Kidd. [7]

"They have no idea that many workers would have had money and freedom to prosper if governments had not stifled their choices, ignored, unpaid and underpaid [their] labour, and misused their earnings and entitlements."

Australians need to become more self-critical and able to own up to their past. Only if they acknowledge the history that caused them shame and guilt can they move on towards integration and healing.

Aboriginal people desire recognition of their past treatment. Let the ‘great Australian silence’ become a great Australian awareness.

The vast majority of non-Indigenous Australians have no idea of the enormous debt they owe to the Aboriginal men, women and children whose labour built this country.

— Dr Rosalind Kidd, historian and author [3]

Further reading

Something Like Slavery — Queensland's Aboriginal child workers, 1842–1945 by Shirleene Robinson reveals how the rapid economic development of Queensland in the 19th and early 20th centuries was due in a large way to the work of Aboriginal children. Some as young as two years old, they were forced to work with white people building the region's industries. This book is the first full-length examination of their exploitation. Drawing on extensive original research, Dr Shirleene Robinson brings to light the exploitation and abuse inflicted on Aboriginal children to benefit white settlers. Many of these children were part of Queensland's earliest 'stolen generations'. Their forcible removal from their parents and family groups caused great pain and suffering that is still felt today.

Settlers, Servants and Slaves - Aboriginal and European Children in Nineteenth Century Western Australia by Penelope Hetherington documents the exploitation of both European and Aboriginal children by the settler elite of nineteenth century Western Australia. In a struggling colony desperately short of labour, early settlers relied on the labour of children. Convicted and neglected children from the poorest sections of this divided society were placed in institutions, where they were trained to become a useful part of the work force. Education services developed slowly, and there was no system of secondary education provided by the government in the nineteenth century. Settlers, Servants and Slaves also shows how concern over "the problem" of children of mixed descent in the last decade of the nineteenth century was to provide the rationale for infamous twentieth century "solutions": the removal of children from their parents, and the establishment of Aboriginal Reserves.

"[And] So We are 'Slave owners'!": Employers and the NSW Aborigines Protection Board Trust Funds is an article by Victoria Haskins published in the journal Labour History (No. 88, May, 2005, pp. 147-164). Scans of the article pages are available at the digital library JSTOR (Journal Storage).

Anti-slavery in Australia is the only specialist legal research and policy centre in Australia focused on the abolition of slavery, trafficking and extreme labour exploitation. Based within the University of Technology Sydney, the Centre is offering free legal advice to individuals who have been trafficked, enslaved or exploited, undertakes research and conducts interactive workshops and presentations, online e-learning training programs and high school education.

If you are curious about numbers, check the Findings section of the Global Slavery Index. For 2016, Australia ranked 52nd with around 4,300 people enslaved.