Politics

Walk-off at Wave Hill: Birth of Aboriginal land rights

Protesting for equal wages Aboriginal stockmen walked off Wave Hill pastoral station in the Northern Territory in 1966. Little did the white station owners know that the strike would become a precursor to land rights legislation almost 10 years later.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

Background of the walk-off

The Wave Hill Walk-off followed more than 80 years of massacres and killings, stolen children and other abuses by early colonists. [1] The memories of their brutal treatment over several generations weighed heavily on the minds of Gurindji people long before they walked off the station.

Pastoralists who were moving into Gurindji homelands considered the blacksoil plains of the Victoria River District to be prime grazing land. Conflicts ensued, and Aboriginal elders later remembered how white stockmen "shot them like dogs", [1] took their women for sexual gratification or let children witness the murder of their parents or uncles.

Consequently, besides being an industrial or land dispute, for Gurundji the walk-off will always also be "a pivotal moment where they chose to wrest back control of their lives after the culmination of 80 years of fear and brutality". [1]

Stockmen protest for equal wages

Aboriginal stockmen, who had always been the backbone of the northern Australian cattle industry, were not paid wage equal to those of their white counterparts.

In fact, it was illegal up until 1968 to pay Aboriginal workers more than a specified amount in goods and money. An attempt to introduce equal wages in 1965 failed because pastoralists argued that equal wages would ruin the industry if paid immediately. It was decided to defer a decision for three years.

In 1966 Aboriginal people first protested for equal wages at Union Camp at Newcastle Waters Station, about 270km north of Tennant Creek [2]. The strike focused national attention on the entitlements of workers on pastoral properties across the NT.

Although they lost the strike, they started a groundswell of resistance to the appalling working standards imposed on Aboriginal people. It was a catalyst for the Wave Hill walk-off.

In January 2009 Union Camp was recognised as a site of historical significance. [2]

23 August 1966 - Australia's first land claim at Wave Hill

But Aboriginal people did not submit to this decision. On 23 August 1966, 200 Aboriginal stockmen of the Gurindji people and their families walked off Wave Hill pastoral station, 600 kms south of Darwin in the Northern Territory, owned by a British aristocrat Lord Vestey.

Led by Vincent Lingiari, a community elder and head stockman at the station, they set up camp in the bed of Victoria River. The camp moved before the wet season of that year and in 1967 the Gurindji Aboriginal people settled some 30 kilometres from Wave Hill Station at Wattie Creek (Daguragu), in the heart of their traditional land, near a site of cultural significance.

One of the first things the Gurindji did after the walk-off was to take the bones of those massacred at Blackfellows Knob around 1924 and accord them with the respect of a traditional burial, by interring them in the caves of the Seale Gorge (Warluck). [1]

The Wave Hill walk-off was well supported, including non-Aboriginal people. Unionists Brian Manning, a Darwin waterfront worker and fervent unionist, organised a strike fund with fellow unionists and Aboriginal actor Robert Tudawali and Roper River man and Union organiser Dexter Daniels. Manning loaded his truck with supplies and made the first of up to fifteen 1,600 kilometre round-trips from Darwin to Wave Hill. Manning’s support was key to the strike’s success.

The strike made headlines all over Australia. While the initial strike was about wages and living conditions it soon spread to include the more fundamental issue about their traditional lands. The Wave Hill walk-off had morphed into a land claim.

Aboriginal leaders petitioned the Governor-General in 1967, requesting a lease of 500 square miles to be run cooperatively as a mining lease and cattle station, [3] and toured Australia to raise awareness about their cause.

The Gurindji Aboriginal people were claiming that this land was morally theirs because their people "lived here from time immemorial and [their] culture, myths, dreaming and sacred places have been evolved in this land". This was the first claim for traditional Aboriginal land in Australia.

While Vestey's company was prepared to hand the land over, opposition to this unusual and new idea was very strong.

The strike went on for nine years until Prime Minister Gough Whitlam visited the site of the strike and made history with a symbolic gesture.

In 2006 the NT government heritage listed the route of the walk-off. [4] A track to share the historic journey with visitors via interpretive signage and specially designed shelters was opened on 19 August 2016, the 50th anniversary of the walk-off.

Map: The location of Wave Hill Station at Wattie Creek in the Northern Territory. Today Wave Hill is the area of the remote twin communities of Kalkaringi (also spelt Kalkarindji) and Daguragu (upper Victoria River region, NT). It's about 9 hours (or 780 kms) south of Darwin.

16 August 1975 – Wattie Creek becomes Aboriginal land

.jpg)

Nationally many people resisted the idea of handing back land to its traditional owners. Five years later (the government had changed too), on 16 August 1975, Prime Minister Gough Whitlam (Labor) handed over title to the land to the Gurindji Aboriginal people—the first act of restitution to Aboriginal people and the start of the land rights movement.

Gough Whitlam pouring soil into Vincent Lingiari's hands has become a defining moment in Australia's history.

The Wave Hill walk-off had paved the way for the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976. In 1975 the Gurindji people bought the pastoral lease with grazing rights to part of the station. After the NT government threatened to resume the lease, the Gurindji lodged a land rights claim.

In 1986 they gained freehold title to the waterhole on Wattie Creek known as Dagaragu, which is located in the Victoria River Region of the Northern Territory.

In May 2004, a memorial to Vincent Lingiari was unveiled as part of Reconciliation Place in Canberra.

Many Aboriginal people fondly remember Whitlam and labelled him 'jangkarni marlaka' (big important man) when he died in October 2014. [5]

The Gurindji's native title claim was finally decided in September 2020 when the Federal Court recognised their native title rights to 5,000 square kilometres of the station. "We're not returning land," said the justice, "what we're doing is recognising that the [Aboriginal] land-holding groups have had interests in this land at least from the time of European settlement, probably for millennia." [9]

Today 700 Gurindji live in the communities of Daguragu, on the banks of Wattie Creek and Kalkarinji, formerly known as Wave Hill. [6] They hope that the native title determination gives them more economic possibilities by allowing them to negotiate royalties from resources companies which explore the area.

Finally, to give back to you formally in Aboriginal and Australian law ownership of this land of your fathers. Vincent Lingiari, I solemnly hand to you these deeds as proof, in Australian law, that these lands belong to the Gurindji people and I put into your hands this piece of the earth itself as a sign that we restore them to you and your children forever.

— Gough Whitlam, August 16th 1975 [5]

Was it successful?

The big question is: Was the walk-off and strike successful? Are Aboriginal workers better off?

Professor Jon Altman from the Alfred Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalisation at Deakin University took a hard look in 2016, the 50th anniversary of the Wave Hill Walk-off and 40th anniversary of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act.

His findings are not encouraging. [7]

"It would be fair to assume that today – 50 years after the walk-off and 40 years after the passage of the federal land rights act – the situation has massively improved and that the problems raised half a century ago have been fixed. But has the situation really improved?

“After a period of thirty years of gradual improvement to 1996, things have gone backwards. In 1966 Aboriginal people could walk-off in protest, but today their choices are more limited, there is less freedom. Back then it was the Vesteys Groups, a privately owned UK group of companies that was mistreating Aboriginal labour, today it is the Australian state.

"The inappropriately-named Community Development Programme is looking to disgracefully exploit Aboriginal workers in regional and remote Australia by paying them less than award wages for a mandatory 25 hours work a week with none of the usual contemporary benefits of work like holiday pay, superannuation or long service leave entitlements. And if people do not comply with draconian work-for-the-dole or train for training’s sake requirements they are breached, they lose their welfare entitlements at historically unprecedented rates and have to survive with no income for periods of up to eight weeks.”

The Wave Hill walk-off in poetry and song

Ted Egan wrote the Gurindji Blues in the 1960s with Vincent Lingiari. Some words are:

"Poor Bugger Me, Gurindji Me bin sit down this country Long before no Lord Vestey All about land belong to we [...] Long time work no wages, we, Work for the good old Lord Vestey Little bit flour; sugar and tea For the Gurindji, from Lord Vestey ..."

In 1991 Kev Carmody composed a song together with Paul Kelly in which they commemorate the Wave Hill walk-off, "From little things, big things grow":

Gather round people let me tell you a story An eight year-long story of power and pride British Lord Vestey and Vincent Lingiari Were opposite men on opposite sides.

The history of the Wave Hill walk-off has also been turned into a children's book, From Little Things Big Things Grow, illustrated by Gurindji schoolchildren and featuring evocative landscape paintings by artist Peter Hudson.

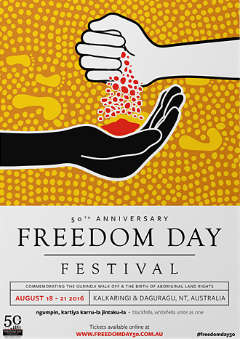

The Freedom Day Festival

The Freedom Day Festival is an annual celebration of the Wave Hill walk-off. It is a key event for the Aboriginal communities and recognises the contribution made by the Gurindji, Mudbara and Walpiri families to Australia's history.

The 50th anniversary of the Freedom Day Festival was held from 19 - 21 August 2016 in the Kalkaringi/Daguragu Aboriginal communities.

See www.freedomday.com.au for more details.