Stolen Generations

A guide to Australia's Stolen Generations

Read why Aboriginal children were stolen from their families, where they were taken and what happened to them. The horrific abuse they suffered in institutions and foster families left thousands traumatised for life.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

Tip: Get free Stolen Generations e-postcards to send to your friends!

Quick overview

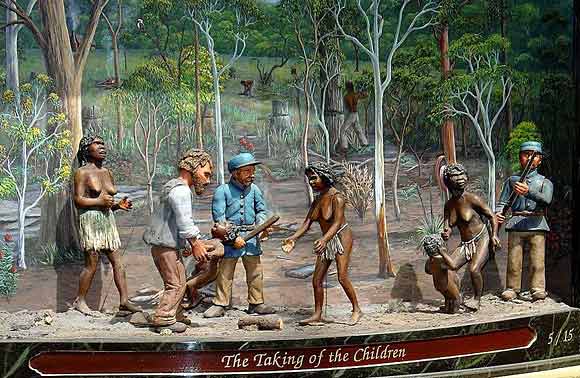

One of the darkest chapters of Australian history was the forced removal of Aboriginal children from their families. Children as young as babies were stolen from their families to be placed in girls and boys homes, foster families or missions. At the age of 18 they were 'released' into white society, most scarred for life by their experiences.

These Aboriginal people are collectively referred to as the 'Stolen Generations' because several generations were affected.

Many Aboriginal people are still searching for their parents and siblings.

Watch this 8-minute video from Australian Screen that summarised the key points of the Stolen Generations:

I feel our childhood has been taken away from us and it has left a big hole in our lives.

— Jennifer, personal story in the Bringing Them Home Report

A guide to the Stolen Generations

Define 'Stolen Generations'

The term "Stolen Generations" is used for Aboriginal people forcefully taken away (stolen) from their families between the 1890s and 1970s, many to never to see their parents, siblings or relatives again. Because the period covers many decades we speak of "generations" (plural) rather than "generation".

Why were Aboriginal children stolen?

This is the most burning question for members of the Stolen Generations. In removing their children white people stole Aboriginal people's future. Language, tradition, knowledge, dances and spirituality could only live if passed on to their children. In breaking this circle of life white people hoped to end Aboriginal culture within a short time and get rid of "the Aboriginal problem".

In the early 20th century under the assimilation policy white Australians thought Aboriginal people would die out. In three generations, they thought, Aboriginal genes would have been 'bred out' when Aboriginal people had children with white people.

"It was a presumption for many years that we girls would grow up and marry nice white boys," says Aboriginal woman Barbara Cummings, a member of the Stolen Generations [1]. "We would have nice fairer children who, if they were girls, would marry white boys again and eventually the colour would die out. That was the original plan - the whole removal policy was based on the women because the women could breed."

Adult Aboriginal people resisted efforts to be driven out of towns by simply coming back. But children taken away were much easier to control.

I grew up feeling alone, a black girl in a white world, and I resented them for trying to make me white but they couldn't wash away thousands of years of dreaming.

— Aunty Rhonda Collard, member of the Stolen Generations [2]

Aboriginal children who were taken away also fed the insatiable demand for station workers and domestic servants. Without these cheap, and often unpaid, labourers white Australians wouldn't have been able to build the wealth and infrastructure that helped them prosper. This is where the Stolen Generations and the stolen wages become one story.

Authorities also took children away pretending that Aboriginal parents would neglect them. There is evidence, however, that kids were malnourished or starving because Aboriginal people were not paid the full wages they were owed [3].

Which children were taken away?

Authorities targeted mainly children of mixed descent, i.e. what they called 'half-caste' Aboriginal children (caution, this is a derogative term!). It was thought these Aboriginal children could be assimilated more easily into white society.

During this time many children were not told that they were Aboriginal and discovered this much later in their lives. So-called 'A grade' babies were not obviously Aboriginal and were fostered out without telling their new parents their heritage. For 'B grade' babies, one could tell their Aboriginal heritage if knowing "what to look out for". [5]

Aboriginal author Sally Morgan wrote about her experiences in her book My Place.

What happened to the stolen children?

Often babies were stolen at birth, and their mother given no chance of seeing them for the first time. They were called 'Blanket Babies' because nurses covered them with a blanket to hide them from their mothers. [5]

The stolen children were raised on missions or by foster parents, totally cut off from their Aboriginality. Many were stripped of their names and called by a number. They were severely punished when caught talking their Aboriginal language.

Some children never learned anything traditional and received little or no education. Instead the girls were trained to be domestic servants, the boys to be stockmen.

Many of the stolen girls and boys were physically, emotionally and sexually abused. Many babies born to girls raped by white men were also taken away from them, sometimes as soon as they were born.

There is no black or white, we are both of those. I am black and I am white. We were the product of white men raping our traditional women. We were an embarrassment. No-one wanted us. They just wanted us out of the way.

— Zita Wallace, taken aged eight years [6]

Boys and girls were brought into separate institutions which they (and some experts) would later compare with German concentration camps and the holocaust. Many tried to run away but few succeeded. Many never saw their parents again or were told they were orphans.

We were each handed a pair of pyjamas with a number Mr Borland, the manager, had given us earlier printed on the pocket, and a shirt and pair of shorts also. I was number 33. Not Bill. Not even Simon. Just number 33.

— Bill Simon, taken away aged 10 [7]

The most infamous institutions are following. Be careful when you mention them to Aboriginal people, a lot of hurt and bad memories might come up.

- Blacktown Native Institution, Western Sydney, is one of the earliest known places where Aboriginal children were taken from their parents (corner Richmond and Rooty Hill North Roads, Oakhurst).It was built specifically to house and indoctrinate children with European culture and customs, and represents the origins of institutionalisation of Aboriginal people in Australia. The institution operated between 1823 and 1829 under the direction of the Anglican Church Missionary Society. [8]

- Bomaderry Children's Home (United Aborigines Mission) operated from 24 May 1908 to 1981 (59 Beinda Street, Bomaderry).

- Cootamundra Aboriginal Girls' Home (Cootamundra Domestic Training Home for Aboriginal Girls), originally a hospital, operated from 1911 to 1969. About 1,200 girls were placed in Cootamundra during this time. It celebrated its centenary on 11 August 2012.

- Kinchela Aboriginal Boys' Home (Kinchela Training Institution) which moved to Kempsey in 1924 (2054 South West Rocks Road, Kinchela). About 600 Aboriginal boys passed through Kinchela, one of the most violent and abusive institutions, before it was closed in 1970. The site is on the New South Wales State Heritage Register and in 2022 was recognised by the World Monuments Fund. www.kinchelaboyshome.org.au

- Mittagong Boys' Home

- Oakhurst Blacktown Native Institution operated from December 1814 to early 1829. At its peak it housed about 20 Aboriginal and Maori children, but children frequently ran away or their parents removed them. The site is considered a "key historical site symbolising dispossession and child removal". [9]

- Parramatta Girls' Home which operated from 1887 until 1986. About 30,000 girls were locked up during that time. The home was also knows as the Industrial School for Girls, Girls Training School and Girls Training Home. Parragirls is a network of more than 350 women who lived in the home. Parramatta Girls is a play by Alana Valentine that is part of the HSC syllabus since 2010, contributing to the survivor's healing process.

- Kahlin Compound, Darwin

- Retta Dixon Home, Darwin

- The Bungalow, Alice Springs

- Box Hill Boys Home, Melbourne

- Moore River Native Settlement, Western Australia (featured in the film and book Rabbit Proof Fence)

Many of those who were stolen established links with the area where they stayed for many years. After they left the institutions these people settled in the area.

However, the women and men also passed on the kinds of abuse they suffered to their own children (intergenerational trauma).

Others did not survive and were buried on site, often dug by other children. Efforts are under way to scan the sites of former institutions for hidden graves. [10]

Sometimes at night we'd cry with hunger. We had to scrounge in the town dump, eating old bread, smashing tomato sauce bottles, licking them.

— Bringing Them Home - Community Guide, children's experiences

Aerial photo of the former Cootamundra Girls Home. The property is near 39 Rinkin Street, Cootamundra, NSW 2590.

How many children were stolen?

That is not easy to answer. Few records of stolen children were kept, some were deliberately destroyed or just lost. Some administrations tried to tout their "successful assimilation" of Aboriginal people by deliberately understating Aboriginal numbers, thus distorting data.

Hence numbers can only be roughly estimated. It is estimated that between 1883 and 1969 more than 6,200 children were stolen in NSW alone [11][12].

A 1994 survey by the Australian Bureau of Statistics stated that one in every ten (10%) Aboriginal people aged over 25 had been removed from their families in childhood [13], a figure which seems to be confirmed by research since the Bringing Them Home Report [14]. Australia-wide numbers are in the tens of thousands.

If you apply this proportion to the 2011 Census figures of the Aboriginal population you'll get around 14,700 Stolen Generations members for that year. Considering those with immediate family who had been removed, an additional 160,000 Aboriginal people are directly affected by the policies of the Stolen Generations. [15]

The [South Australian] government was unable to say how many Stolen Generation people live in the state.

— Statement in a 2007 article about the first court-ordered compensation ruling [16]

When were the children stolen?

Towards the end of the 19th century authorities started to take children away without a legal framework. A framework was established in 1909 with the Aborigines Protection Act.

During the 1960s the child removal process slowed down but continued well into the 1970s. Some of the schools and missions who held the Stolen Generations did not close until the early 1980s (e.g. Bomaderry Children's Home in NSW [17]).

What were the effects on the stolen children?

The effects on the stolen children and their families were profound and are ongoing.

Aboriginal people suffer from many social and personal problems including mental illness, violence, alcoholism and welfare dependance, but there are many more issues members of the Stolen Generations suffer from.

Is there any official documentation of the Stolen Generations?

On 26 May 1997 the landmark Bringing Them Home report was tabled in Federal Parliament. The report was the result of a national inquiry that investigated the forced removal of Aboriginal children from their families.

The report was a vital step in the healing journey of many Stolen Generations members. It was the first time their stories were acknowledged in public. It was also the first time it was formally reported that what governments did to these children was inhumane and the impact has been lifelong.

The full report is available at the Australian Human Rights Commission.

You can also watch the Commission's 30-minute documentary about the separation of Aboriginal children from their families.

But the report was not the first publication documenting the Stolen Generations. Aboriginal author Barbara Cummings, herself a member of the Stolen Generations, published her story in her 1990 book, Take This Child, laying bare the abuse and emotional deprivation she and others experienced after being taken from their families.

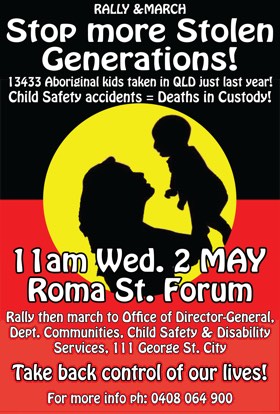

More children are being taken today than during the Stolen Generations period

- 2,785

- Number of Aboriginal children in out-of-home care in 1997 when the Bringing Them Home report was tabled in Federal Parliament. [18]

- 23,344

- Number of Aboriginal children in out-of-home care in June 2020. [19]

16% - Percentage of Aboriginal children in the hands of child protection services in 2017-18 (8 times the rate of non-Aboriginal children). [20]

- 9.7

- Times Aboriginal children are more likely to be removed from their families than non-Aboriginal children. [21]

- $2b

- Money the NSW government spent on child protection and out-of-home care in 2020; on early intervention: $150m. [21]

37% - Percentage of out-of-home care population who are Aboriginal children in 2020; [21] figure for 2014: almost 35%. [22]

6% - Percentage of the total child population in Australia which is Aboriginal in2020; [21] figure for 2014: 4.4%. [22]

Children continue to be taken from their families. The Department of Community Services (DoCS) has the authority to remove children from their families if they were "at risk of significant harm".

This Parliament resolves that the injustices of the past must never, never happen again.

— Former prime minister, Kevin Rudd, in his apology to the Stolen Generations in 2008.

If you don't already know, the Stolen Generation scenario still applies today and has been here for a long time and will continue to be here.

— Paul Ralph, CEO of KARI Aboriginal Resources Inc [23]

About 60 children are being taken away every month by child protection services, says Elder Djiniyini Gondarra, who represents 8,000 Yolngu people of east Arnhem Land. [24] "Children are being taken away from us at numbers not seen since the Stolen Generations."

Indeed, since the National Apology to the Stolen Generations in 2008 the number of Aboriginal children in care has increased by 65%. [22] In 2020, NSW had the highest rate of Aboriginal children in care. [21]

Story: "The year that Kevin Rudd gave his apology ... I was taken."

Bundjalung woman Vanessa Turnbull-Roberts, a young paralegal, remembers a traumatising night – the night she was taken away from her family. [25]

"The Department of Community Services [DOCS, now the NSW Department of Family and Community Services] removed me from my family in 2008 when I was 10. It was around 10 o’clock at night, and I was in bed. [...] I looked out the window and saw all of these red and blue flashing lights.

"I heard a knock at the door and it was a caseworker. She said, 'Hug your dad one last time, you’ve got to come with us.' I remember hugging my dad so tight that I could feel his tears drop on my shoulder.

"When I was in the DOCS car, I vomited because I’d been crying so much. I didn’t know what was going on. I was placed into an emergency foster home that night. I remember the caseworker saying to me, 'You can’t go home because your parents neglected you and your parents don’t know how to look after children.' I was really confused, because I remembered my dad raising my nieces and nephews and cousins and playing a prominent role in their lives. I was like, 'What do you mean that my dad doesn’t know how to raise children?'

"I went to around eight or 10 foster homes in that first couple of years. That’s considered a low number. [...] The foster homes that I went to were white – they weren’t my kin, even though my aunties and uncles had put their hand up to take me in. [...]

"The year that Kevin Rudd gave his apology to the stolen generations was the same year I was taken. I remember everyone felt so proud as a nation, but the reality is, the same executive powers are removing our babies. This is still occurring today."

Aboriginal children are

- almost 8 times more likely to be the subject of departmental intervention,

- 9 times more Aboriginal children are on care and protection orders, [26] and

- 10 times more Aboriginal children are in out-of-home care than non-Aboriginal kids. [27]

The current generation may one day grow up to say they, too, had been removed from their families.

In Victoria, only about 60% of Koorie children in care remained connected to their family and culture. [28] In 2020, a "staggering" 81% of Aboriginal children were on long-term guardianship orders, which means they are in state care to the age of 18. [21]

The number of Aboriginal children being adopted is also disproportionally high. In 2020, 95% of adoptions have been to non-Aboriginal carers, and they all occurred in NSW and Victoria. [21] NSW allows adoption without parental consent.

In 2012, Olga Havnen, a senior Northern Territory government official, revealed that more than $80m was spent on the surveillance of families and the removal of children compared with just $500,000 on supporting the same impoverished families. Her warning of a second Stolen Generation led to her sacking. [29]

Why are they still taken away?

Intergenerational effects of separation from family and culture are partly to blame: parents who were themselves stolen as children are passing on this trauma to their own kids.

But many government workers who decide about removing children seem to have difficulty telling neglect from poverty.

Larrakia elder Dr Christine Fejo-King was a consultant to the NT Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory. She found neglect was the biggest reason why Aboriginal children were removed from their families, but the system was confusing the effects of absolute poverty with the concept of neglect. [30]

"There's a difference between absolute poverty which is often then equated to neglect as opposed to actual life-threatening situations for that child as a result of the people that they're living with in an unsafe place," she said.

Many case workers come from the middle class, have never worked with Aboriginal people and have difficulties making the right call.

Other reasons include a European-centred view on how a child should be looked after. That view considers it unacceptable for a child to stay over with different relatives on different nights, but it is part of the cultural roles these relatives are playing in raising the children. [31]

Aboriginal children are mostly removed for ‘neglect’ or ‘emotional abuse’. I have seen first hand how these judgements are made on a racist basis, or arise directly from the extreme poverty faced by families.

— Padraic Gibson, Senior Researcher, Jumbunna Indigenous House of Learning, University of Technology, Sydney [32]

Homework: Three generations fearing for their kids

Here is what Aboriginal mother Kelly Briggs said about her own fears, those of her mum and of her grandmother [33]:

"What happens if the small amount of work I have gained dries up [...]? What if money again becomes so tight that shoes, uniforms, excursions, lunches or transport [...] become issues that keep my kids from turning up at school on occasion? What exactly is the scope of these truancy officers? Do they give my kids lunch? Buy them uniforms? Will my name be added to some department of community services list somewhere? Will there be a mark upon my name that gives rise to visits from people who can remove my children from my care?

"I spoke honestly and frankly with my mother about my worries. She was amazed that this is still happening [...]. We spoke of her own mother's obsession with cleanliness, which sprang from her fear of the dreaded 'welfare man', a government employee who could come to your house and demand to be let inside to ensure your house was clean, that there was adequate food available, that the children were going to school.

"She then went on to tell me about her own fears when she was raising me and my siblings: the absolute terror she felt when she had to collect food vouchers of some nameless person swooping in to take us kids off her because she was facing hardship after my father passed away. The tremble in her voice as she recounted this broke my heart."

Questions

- Why is Aunty Kelly fearing her kids can be taken away?

- Find out how much Kelly has to pay for the items she has listed.

- Find one word that represents the effect the women's worries had on their lives.

- In which years were the women in Kelly's family worried about their children?

- Research what rights the "welfare man" had, which government agency was allowed to take kids "facing hardship", and what can happen today if kids don't turn up at school.

- With the background of Kelly's story above, explain this statement of her:

"In the back of my mind, I always hear the voice that says 'don’t ever let anyone know you’re doing it tough, because they will take your kids from you'." [33]

The new Stolen Generation is much larger

A Special Commission of Inquiry into the Department of Community Services found that in March 2008 there were 4,458 Aboriginal children in out-of-home care, 4 times as many Aboriginal children as were in foster homes, institutions or missions in 1969, during the Stolen Generations. [35] 8% of Aboriginal people aged 15 years and over were removed from their natural families in 2008. [36]

From February 2001 to August 2007 the number of children reported to DoCS increased by 300% to 55,303. [37]

In Queensland, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children represent 6.3% of the under-18s, yet in 2006 they made up over 25% of those in out-of-home care. [38] In 2011 in New South Wales, 33% of Aboriginal children and young people were in the care system, and the national figure was 36%. [23]

In Western Australia, 46% of children in state care were Aboriginal in 2011, in regional areas "nearly 100%" were thought to be Aboriginal. [39]

Filmmaker John Pilger investigates this new stolen generation in Utopia. "The theft is now higher than at any time in the last century," he found. In mid-1997 there were 2,785 Aboriginal children in out-of-home care across Australia. By mid-2012 there were 13,299 - almost a five-fold increase.

Pilger notes the NT government spent $80 million in one year removing children but just $500,000 supporting impoverished families. [40]

If you don't fix the underlying issues—unemployment, housing—that contribute to child protection, Aboriginal children will continue to be removed from their families.

— Julie Tommy Walker, Aboriginal leader and Innawonga woman [39]

If Aboriginal children are put into foster care, they should at least be put into other Aboriginal families. These children's safety is "always grounded in their culture" [41] because they need to remain connected to the communities and be sure and strong in their cultural identity.

But in 2013, in the Northern Territory, about 66% of children are taken away from their culture and community. To no surprise, one-third of the Aboriginal children removed to non-Aboriginal homes have told the government they had lost all contact with family. [42]

Child protection workers who lack knowledge about Aboriginal culture are another problem. Without understanding the context they make assumptions based on racist stereotypes which puts children at risk of being taken. [20]

The madness of the past is still the cruelty of today.

— Jeff McMullen, journalist [42]

It is no surprise then that Aboriginal women are trying to protect their children at all costs. They go as far as staying in abusive relationships because if they report domestic abuse, child protection services are likely to take their children and the woman might become homeless. Aboriginal people are five times more likely to experience domestic violence. [20]

When child protection services share offices with family violence services, the women fear a removal is more likely. [20]

Story: Only one day a year

An Aboriginal Perth father can only see his two daughters for what equates to one day a year. [43]

His two children have been removed from their mother's care by the Department of Child Protection (DCP) and placed with non-Aboriginal carers for 4 years.

The father lodged a complaint saying that the department failed to let the children know about their family and culture. He was only allowed to see his daughters one hour every fortnight which "equates to one day a year".

The man's mother was a member of the Stolen Generations. "[I ] saw my mother and all her siblings taken from my grandparents, and my grandparents taken from my great grandparents," he said.

Grandmothers Against Removals (GMAR)

When Aunty Hazel Collins witnessed the removal of her daughter Helen's baby son, an event she recalls in the film After the Apology, it made her realise she had to do something.

"In 2014, my last little baby was taken off my daughter, and at that removal there were about eight, nine police and four DoCS [Department of Community Services] workers. And I promised, promised my little baby and his mum, there'd be no more." [31]

Aunty Hazel went on to found Grandmothers Against Removals (GMAR) the same year, a network of grandmothers from Gunnedah in northern NSW that fights against the systematic removal of Aboriginal children from their families and highlights the process of removal used by the New South Wales Department of Children’s Services.

Watch Aunty Hazel speak at a protest in front of Parliament House in Sydney:

Was it legal to steal Aboriginal children?

With all the pain and trauma caused by the child removal policies one has to ask: Was this legal? Didn't these laws violate basic human rights?

These questions were put to Australia's High Court in 1997 when two members of the Stolen Generations sued the Commonwealth (Kruger vs Commonwealth). They argued that the laws breached basic fundamental human rights such as the right to due process before the law, equality before the law, freedom of movement and freedom of religion.

In a "dramatic demonstration of Australia's lack of rights protection" [44] the High Court held that none of these rights were protected. We are not talking Aboriginal rights here—we are talking human rights!

In other words, it was perfectly legal for Australia's government to forcibly remove Aboriginal children.

Australia's failure to protect basic human rights falls hardest on the poor, the marginalised and the socioeconomic disadvantaged. That is, they fall hardest on Aboriginal people, families and communities.

Stolen Generation reunions

Members of the Stolen Generations yearn most to reunite with their lost loved ones. Sometimes family members find each other just in time, sometimes just a short time too late. Services which help people reunite need more funding.

We didn't find our family until I was 11 or 12.

— Prof. Larissa Behrendt, Aboriginal barrister [45]

Stolen Generation member dies only months after reunion

A 107-year-old member of the Stolen Generations died only months after she was finally reunited with members of her original people in Port Hedland, Western Australia. [46] Belinda Dann's life is a sad example of many other members of the Stolen Generations, many of whom died broken-hearted because they never saw their loved ones again.

Belinda was six years old when she was taken from her mother. Along with sisters she was taken to Beagle Bay mission in north-western Australia. When they asked for their mother they were told she would come which she never did. She married as a teenager and moved to Port Hedland. She remembered her Aboriginal name but did not know who she was and where she came from.

By coincidence one of Belinda's grandsons mentioned her Aboriginal name in a conversation with an Aboriginal girl who had heard of Belinda and was connected to her people. A 100-year-long search was over. Belinda met her people and, incredibly, started speaking in her native Aboriginal language again. Four months later she died.

We didn't know we were related. You find it out at 20 or 30, sitting in a pub drinking.

— Richard Pittman, Stolen Generations member, taken aged four [47]

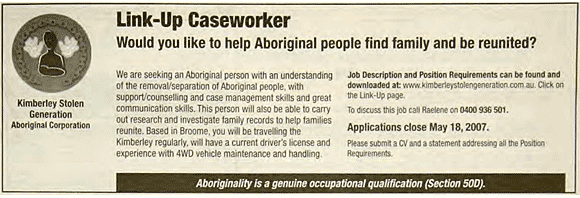

Re-union services need more funding

The main service members of the Stolen Generations can use to find loved ones is Link-Up (see below). But Link-Up needs more resources to work effectively. [48] Reunions take too long to be organised, and once they had been, they were far too short, or people were unable to afford return visits.

Some Aboriginal people feel like being "stolen again" when they are unable to revisit their newly found family. [48]

Healing members of the Stolen Generations

On 13 February 2009, one year after it apologised to the Stolen Generations, the Australian government promised to establish the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Healing Foundation.

The foundation is designed to deal with the "trauma experienced by all Aboriginal people as the after-effect of colonisation", [50] but with a particular focus on the Stolen Generations.

It won't deliver healing services, instead it funds healing work, educates communities and social workers and evaluates healing programs to find out what works.

According to Aboriginal trauma and grief specialist Dr Greg Phillips, healing is "a spiritual process that includes recovery from addiction, therapeutic change and cultural renewal". [50]

Healing is not just another government program. It has taken many generations to get to this level of trauma and it will take quite a few to fully recover from it.

— Dr Greg Phillips, Aboriginal trauma and grief specialist from the Waanyi people [50]

Many members of the Stolen Generations attend annual reunions where they meet fellow Aboriginal people to share their stories and experiences they endured as children in the institutions where they were raised. The Link-Up service (see bottom of this page) often supplies funding for these reunions. For many this is the start of their journey of healing.

Denying history: 'Not stolen, but rescued'

A significant number of Australians disagreed with the apology delivered in February 2008 to the Stolen Generations by Prime Minister Kevin Rudd. Here are their main arguments:

- The Stolen Generations don't exist. Some people simply and flatly deny that children were stolen. They want to see 'proof' and claim no-one could 'find' them. For example, journalist Andrew Bolt claimed the Stolen Generations were "a giant intellectual fraud with unforgivable consequences" and "no one has yet produced a single child who was stolen under a government policy to remove children just because they were Aboriginal and not because they needed help." [51]

- Aboriginal children were 'rescued'. Supporters claim that Aboriginal children were not stolen but 'rescued' from a family and community environment that was "rife with rape, incest, drug and/or alcohol abuse and insanitary living conditions". [52] The Aboriginal children were 'given a chance'.

I've asked my granny if she thought she was rescued. She replied, "I didn't need rescuing from my mother's love."

— Che Cockatoo-Collins [53]

- 'We did not do it'. People who refuse to apologise to the Stolen Generations feel that they or their ancestors had no part in what happened, hence shared no responsibility for the pain caused.

- An apology leads to compensation claims. Many people fear that after the apology "a flood of compensation claims will be forthcoming" running to "millions of dollars". [52]

The "white stolen generations"

Did you know that in Australia there is another stolen generation, one which shares the pain and consequences? It's called the "white stolen generation" to distinguish it from the Aboriginal stolen generation.

In the five decades up to 1982, the newborn babies of young, single women were forcibly removed from them for adoption, a practice sometimes called 'baby farming'. Mothers were drugged, tethered to beds, not allowed to see their babies, told they were dead. [54] Many of these adoptions occurred after the mothers were sent away by their families due to the stigma associated with being pregnant and unmarried.

More than 250,000 white mothers lost their babies to forcible removal at birth by these past illegal adoption practices. Groups such as Adoption Loss Adult Support and Apology Alliance offer help and support.

Between 2010 and 2012 apologies were offered by Western Australia, South Australia, ACT, New South Wales, Victoria and Tasmania. Prime Minister Julia Gillard offered a national apology to those affected by forced adoptions in 2013.

Story: "My birth father never knew I existed"

Here is the story of a member of the white stolen generation: [55]

Both my parents were given up to adoption, as was I. In my case my mother, at the time aged 16, was forced by her adoptive mother to give me up. She had no say in the matter and it's something that she had great difficulty dealing with for 42 years till the time that I tracked her down.

My birth father was never even told of my existence, and if not for a chance run-in with my mother ten years after my birth in Sydney would have never even known I existed. He was never asked for permission to give me up for adoption.

My birth mother's adoptive family went to great lengths to hide the fact that their teenage daughter was pregnant. They sent her off to Auckland, NZ, to give birth to me then give me up.

It wasn't until three years ago, when my birth father in Melbourne tracked me down, that I finally learnt the truth.

Australia is not the only country where children were stolen from their mothers. Countries around the world share similar painful histories.

Stolen Generations resources

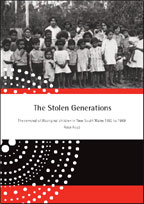

Free Stolen Generations booklet

A must-read is the report by Peter Read, 'The Stolen Generations - The removal of Aboriginal children in New South Wales 1883 to 1969'.

Published in 1981 it was then a ground-breaking first attempt to document the devastating consequences of the forced removal of Aboriginal children from their families.

The report's chapters are: 2006: The return of the Stolen Generations, Introduction, A typical case, The laws regarding children, The number of children taken, Life in the homes, Employment, Fostering, Going home, The effects, Why did they do it?, Appendix.

The 34-page report comes with several black-and-white images and can be downloaded as a PDF file from the NSW Department of Aboriginal Affairs.

Free Bringing Them Home DVD

The Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, a government body, published a DVD in 1997. The free DVD is based on the Bringing Them Home Report which was released on the 26th May that year.

The DVD is a 32-minute documentary, interviewing Aboriginal people of the Stolen Generations and showing historical footage. It is a must-see for all interested in learning more and listening to the stories of Aboriginal people who were stolen. But be warned: The content is sometimes heartbreaking.

The first DVD is free, any further copy is just AUD 5. To order your copy send an email or letter to:Human Rights & Equal Opportunity Commission Level 8, Piccadilly Tower 133 Castlereagh Street Sydney NSW 2000 www.humanrights.gov.au [email protected] Phone: 02 9284 9672 Fax: 02 9284 9611

Watch movies about the Stolen Generations

A very good movie which tells the story of three young girls taken away from their family is Rabbit-Proof Fence by Phillip Noyce.

Baz Luhrmann's Australia also treats the Stolen Generations as a central theme of the movie.

The documentary Lousy Little Sixpence was the first film to tell shocked Australians the story of five girls stolen from their families.

Some short films by Aboriginal directors discuss Stolen Generations, e.g. Back Seat by Pauline Whyman or Bloodlines by Jacob Nash.

Or try the award-winning documentary Why me? - Stories from the Stolen Generations by Rick Cavaggion.

The film Children of the Open Road (1992, original title Kinder der Landstrasse) presents striking parallels between the Stolen Generations and Swiss government policies towards the Rom (gypsies) in the first half of the 20th century.

More movies about Aboriginal people or by Aboriginal directors

I was crying for the kids. It brought back personal memories for us. I was like him. I was like them. I was taken away.

— Dorothy Beto, stolen aged 7 years, reacting to the movie Australia which tells about the Stolen Generations [56]

Teacher resource: Two ways to teach about the Stolen Generations

When members of the Stolen Generations tell their stories in schools students are often in tears. Some stories might be too harsh for them.

Some teachers have found softer ways of teaching [57] which still show the full emotional impact the policies had on people.

- Role playing. Children role play, for example, "we're going to take you to live with us because we think it's better. How do you feel?"

- Tearing drawings. Students make a drawing of their family at home and include valued items such as pets or computers. The teacher then tells the story of stolen children and, while walking around the room, tears away part of each student's drawing. A student could then talk about how they felt about their valuable work being ripped apart and how they would feel being ripped from their family.

Stolen Generations organisations

There are a few organisations helping Aboriginal people from the Stolen Generations.

National Sorry Day Committee (NSDC)

The community-based National Sorry Day Committee was formed in 1998 after the Bringing Them Home report recommended that a National Sorry Day be held each year on 26 May "to commemorate the history of forcible removals and its effects."

The NDSC aims to achieve all 54 recommendations of the Bringing Them Home report, and its Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal supporters work together with Stolen Generations members, Aboriginal communities, government, social justice and community organisations to achieve this goal.

Link-Up

Founded in 1980 and based in New South Wales, Link-Up helps members of the Stolen Generations to find their relatives. It also offers counselling to newly reunited families.

Link-Up has offices in almost every Australian state. In South Australia from 1999 to 2007 Link-Up arranged 160 family reunions and brought together 4,915 people. AIATSIS offers help to find your family.

Family Link

Family Link was established in 2009 to identify family and kin placements for Aboriginal children in foster care.

The service, funded by Link-Up, works with the Department of Community Services to place them with other family members when Aboriginal children cannot live safely with their parents.

While only 4% of NSW's children are Aboriginal they make up 31% of all placements.

Family Link

Hazelbrook, Blue Mountains, NSW 2779

Family Records Service

The Family Records Service helps Aboriginal people in NSW access records about themselves and their families, particularly members of the Stolen Generations.

The Service is run by the Department of Aboriginal Affairs which is the custodian of the records of the Aborigines Welfare Board.

Family Records Service

NSW Department of Aboriginal Affairs

Level 13, Tower B, Centennial Plaza

280 Elizabeth Street

Surry Hills, NSW 2010

Family Records Service

Find and Connect

Find and Connect is a resource for the Forgotten Australians (all Australians who have been 'in care', including British Child Migrants and the Stolen Generations) who wish to find their history. It does not provide access to personal records, but helps individuals locate institutional records about them.

Find and Connect can help those of the Stolen Generations identify which institution(s) they received out-of-home 'care' in. For those wishing to find out more about their past it is then possible to find out where the institution's records are kept and how to access them.