People

Stereotypes & prejudice of 'Aboriginal Australia'

Don't believe everything you read about Aboriginal Australian people. We expose the common "good" stereotypes used in the tourist industry.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

Selected statistics

-

93% - Percentage of Aboriginal Australians who think Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians are prejudiced against each other. [1]

-

71% - Percentage of non-Aboriginal Australians who think the same. [1]

-

18% - Percentage of surveyed Aboriginal people who experienced racial prejudice with local shop owners or staff in the past 12 months; with police: 16%; with doctors, nurses or medical staff: 14%. [2]

What is a stereotype?

Before we discuss stereotypes we need to know what a stereotype is.

Definition: Stereotype

The Wikipedia defines a stereotype as [3]

- a generalised perception of first impressions,

- judging with the eyes/criticising ones outer appearance,

- a conventional and oversimplified conception, opinion, or image,

- forms of social consensus rather than individual judgements.

The word ‘stereotype’ comes from the Greek ‘stereo’ and ‘typos’ = ‘solid impression’.

Stereotypes surface when you are with a group of people and you hear them affirming that, for example, “all Aboriginals are lazy”. If you asked that person you would probably find out that they actually have never met an Aboriginal person which would have allowed them to reach an informed opinion.

Stereotypes are dangerous and can lead to prejudice and racism.

Stereotypes are incomplete and inaccurate beliefs that some people hold about groups of other people [4].

Example: Aboriginal Associate Professor Karen Martin teaches university students in Queensland. She found that of the 600 students in her classes, fewer than one third had ever had a conversation with an Aboriginal person. “And yet most had a strongly held opinion or belief about Aboriginal people—generally negative,” she says [5].

Scientists found that our brain responds more strongly to information about groups who are portrayed unfavourably [6], which is often the case with Aboriginal people in the media. The negative groups then become treated as more and more negative.

When we cluster people into groups with a variety of expected traits we are less overwhelmed by information. But negative stereotypes are more difficult to reverse, and if you haven’t been brought up in a liberal family you might have more difficulties unlearning prejudice. [6]

I once received an email asking for “information on this wonderful history” of Aboriginal people in Australia. Had the author known more about Aboriginal history they wouldn’t have used the word “wonderful”.

Test: Do you hold stereotypes?

Many reduce their perception of Aboriginal people to either be disadvantaged or talented exceptions. Is the following all you do?

- You celebrate individuals such as Rover Thomas, the Bangarra Dance Theatre or Cathy Freeman.

- You admire dot paintings on lounge room walls.

- You condemn endemic violence and out-of-sight Third World conditions.

- You hope the Australian government will do something, anything, about it.

- You ignore the drunks on the street and avoid walking the streets of Redfern.

I’m Aboriginal, But I’m Not…

Listen to Aboriginal people who don’t fit the common stereotype:

Homework: How would you respond to these statements?

Unfortunately a large portion of the majority – that is, white Australians – accept a certain level of prejudice. You can tell when you listen carefully:

- “I don’t have a problem with [insert minority group], provided they come the right way / assimilate…”

- “Aboriginal people need to get over the past and get on with things…”

- “I don’t have a problem with racism, I just don’t like [insert minority group], that’s different…”

- “Don’t be so politically correct, it’s all in good fun [usually said after racist remark]...”

- “I’m not racist, my [insert friend, colleague etc] is [insert race reference]...”

Write a response you could give to each of these statements.

What could your response trigger in the other person? Could you improve your response?

Stereotypes about Aboriginal Australians

Research has found “entrenched negative stereotypes” of Aboriginal people in Australia [8].

Stereotypes can take many forms and shapes. Some of the more common ones say that Aboriginal people… [9][10]

- are primitive and nomadic,

- lack complex laws and social organisation,

- are drunks,

- are violent,

- live in the outback,

- are un-educated no hopers,

- are involved in too much crime,

- receive too much from welfare,

- get more than the whites,

- eat the wrong foods (white sugar, flour, McDonalds, etc.),

- don’t have a religion, have sinned and need to pray for forgiveness,

- don’t use the land they get for free,

- get treated too leniently by police and courts,

- do not want to work and are lazy,

- must fit the image of a dark-skinned, wide-nosed person (i.e. a ‘full-blood’),

- live a traditional tribal/ancient lifestyle,

- are not really attached to their land because they live on the fringe of towns and cities,

- are like leeches and drain away each others’ resources,

- are problems (‘the Aboriginal problem’) and Aboriginal people have problems.

Deconstructing stereotypes

If I asked you to name three symbols of Aboriginal culture, you wouldn't disagree with dot-paintings, boomerangs and didgeridoos, right?

While the tourist industry wants to make us believe these are items that represent Australian Aboriginal culture, they actually don't.

First we need to remember that there is no single Aboriginal culture. Australia is home to many Aboriginal nations who are as diverse as other groups of nations, for example Europe.

All three symbols come from specific areas of Australia because they won't work elsewhere or wouldn't be available in other places.

Dot-painting is an art form that emerged when a European art teacher worked with an Aboriginal community in the Northern Territory in the 1970s. They were a result of abstracting sacred patterns.

Boomerangs need wide, open spaces to be able to fly the typical arcs that bring them back to their thrower. This would be impossible in any of the forested areas of Australia.

Didgeridoos are made from wood that has been hollowed by termites. But the inside of trees is only one of five habitats of termites because many termite species don't eat wood. [11] Since these drywood termites obtain all their moisture from the wood they need high humidity to survive. This limits the areas where artists can find hollow wood.

Spot the stereotype!

In a parody of One Direction’s song What Makes You Beautiful, Frankie Jackson takes to comedy to portray some of the stereotypes about Aboriginal people. How many can you find in this clip?

Stereotypes are myths we copied from others without inquisitive verification. But you’ll be surprised that most of the myths about Aboriginal culture are not true.

Besides individuals who readily believe those stereotypes, the mainstream media’s focus on negative Aboriginal issues creates much hurt when it presents the problems of individual Aboriginal people as problems of all Indigenous Australians.

The education system also contributes to stereotypes when students learn of the negative aspects of Aboriginal history rather than contemporary Aboriginal studies which can be very positive, especially with regard to sporting (such as Rugby League) and educational achievements.

Further, many Australians believe that ‘we are not responsible for the past’ and don’t owe Aboriginal people anything, a view advocated for many years by former Prime Minister John Howard.

The racist stereotyping is alive and well in Australian culture. Never mind that these stereotypes can be shown for the lies that they are, racists never let truth or facts hold them back. I'm Aboriginal and I am aware of the crap every freakin' day!

— wotzthepoint? on Yahoo Answers [12]

Homework: Spot the stereotypes!

The following text is a comment from Creative Spirits’ Facebook page in response to a post about the Western Australian government considering shutting down Aboriginal communities.

Examine the comment carefully:

“Has anyone considered that leaving these communities open is continuing to keep the aboriginal community out of site [sic] and out of mind. By all means keep your cultural heritage which is vital for any race, but let’s get real. A community that has no chance of a sustainable income producing industry, no chance of continuing employment and small family populations is going no where [sic]. What about the children in these communities who never learn to speak english and have trouble putting a sentance [sic] together. What chance are they going to have in the real world.”

Questions

- How many stereotypes are in the text above?

- Which ones are they?

Story: They call you…

They call you Boong, they call you Abo, they call you Coon. They see your skin and think it’s dirty.

When you smile they say ‘they’re a happy one’. They see you work hard and say ‘they must be one of the good ones’.

They congratulate you not for what you have done, but just that you were able to do it… ‘they have potential’. When you argue with your intellect, they are surprised by your intelligence… ‘they’re smart for one of them’.

They don’t see your culture, they don’t see your pride, they don’t see that you are a person in your own right. Yes, you are a good black man. But you are also a good man.

They say you are smart for a black woman. This discounts your intelligence; you are a smart woman. We call you strong, we call you proud, we call you black.

We see your skin as a coat of armour, protecting your spirit and your Dreaming.

You smile because your spirit is strong. You smile because they cannot harm you with their hurtful words.

You work hard, not for their accolades, but for your own and you work for your family. This, they do not understand… but they have potential.

Intellectually you are beyond their par, for you know their world and your own. They only know their way… but they are smart for one of them.

Every day you carry your culture, every day you carry your humanity, every day you carry with you your Dreaming. This makes you a strong black person.

Yes, you are a good man. And I feel strong that you never lose sight of the fact you are a good black man.

You are a smart woman. And I am proud to say you are an intelligent and inspirational black woman.

They call you names. All but your own.

I will call to them, and say ‘these may be your words’ but he is my brother, she is my sister, and today your hurtful words mean nothing. [13]

Resource

Susans Birthday Party is a short 5-minute film about a six-year-old Aboriginal girl with red hair and fair skin who’s teased at school as she is not the stereotypical Aboriginal.

Written and directed by Maureen Logan, the film is available through Keeaira Press.

An old stereotype is in your wallet

Did you know that an old stereotype about Aboriginal Australians is in your wallet? Take out one coin each for five cents, ten cents, twenty cents, one dollar and two dollars, then see what you get.

Australia’s coins as shown above represent Australia’s fauna—or do they? Which coin is the odd one out?

Most coins were designed and introduced in February 1966 [14], more than a year before Aboriginal people were counted as citizens in their own country. It was a time when they were still thought to ‘die out’ eventually and politics of the Stolen Generations would be carried on for at least another ten years.

The series of coins suggests that Aboriginal people were seen as part of the landscape. Ironically the ‘native tree’ shown next to the head of the Aboriginal man used to be called ‘blackboy’, a reference to Indigenous people not only because the grass tree, as it is now known, has a black stem after a bushfire, but also because it develops a spear-like shoot which holds the flower and can be up to two metres in height.

You see, this is where we fit into the white scheme of things, as fauna, part of the animal kingdom, part of the landscape.

— 'Craig', an Aboriginal character in John Damalis' book 'Riding the Black Cockatoo'

One might argue that the one dollar and two dollars coins are not really part of the others because they were designed and added in 1983 and 1987. The fact remains, however, that Aboriginal people might be offended and think otherwise.

Where do stereotypes come from?

The definition of a stereotype above implies that people who communicate them rely on unverified first impressions and oversimplified concepts. Because they don’t want to or cannot find out the truth they rely on views readily available to them.

The media is a prime supplier of these simplified views and itself prone to, and a distributor of, stereotypes.

How many times did you read about a dysfunctional, violent Aboriginal community or drunk Aboriginal people getting into trouble?

And how many times did you read a success story about an Aboriginal person, in health, sport or business?

This is where the media forms and reinforces Aboriginal stereotypes. Racial stereotyping in the media is institutional and results from news values and editorial policies [4].

For Aboriginal artist Bindi Cole this leads to a disconnection between the broader community and the Aboriginal community. “People don’t even understand that in urban areas there [once] were Aboriginal people. They see what they see on TV and think ‘that’s what Aboriginal people are’ and, if you don’t fit into that, you’re not Aboriginal. They think there can’t have been any evolution of Aboriginal people in the last 200 years.” [15]

Politicians who fail to visit a broad range of Aboriginal communities to discuss matters with people first hand are susceptible to stereotypes which then influence their politics. John Howard’s first visit to an Aboriginal community came in February 1998, two years after he took office, and during his 12 years as Prime Minister he never visited any communities other than in far north Queensland and the Northern Territory [16].

People stereotype the Aboriginal race, But theirs I never do disgrace. Drugs, no school, drinkers that's all they know Of a people with so much more to show. I hold my head up so high For my race I would die…

Poem by Salote Bovoro, a 14-year-old girl.[17]

Aboriginal youth become the stereotypes they see

A dangerous thing about stereotypes is that they can influence a young Aboriginal person growing up. As they realise their different heritage and start searching for their identity, they are vulnerable to internalising the beliefs and misconceptions their fellow Australians hold about them.

“If this is what people think that being Aboriginal is, then maybe that’s what I’m supposed to be,” says young Aboriginal woman Belinda Huntress from northern NSW about this identity-searching time in her life.[18] “So what I started doing was colluding to these stereotypes.”

Watch her full speech on TEDxYouth:

How can I avoid stereotyping?

It is not easy to detect that you are holding stereotypes when you are on autopilot. Follow these steps to change:

- Become aware that you hold stereotypes. We are all human and hold stereotypes of some kind. The first step is to raise your awareness that you do without judging yourself for it. Realise that you copied certain beliefs from others without verification (this is much easier anyway).

- Question statements. With your sharpened awareness you can now detect generalising statements like “All Aboriginal people are lazy”. Start questioning them by asking “Why do you think so?” Question not only people, but also any media you consume.

- Inform yourself. Well done for reading Creative Spirits. Information is the best cure to stereotypes. Start investigating, ‘Are Aboriginal people really lazy?’ Check out publications from the Australian Bureau of Statistics. It is vital that you go to trustworthy, authoritative sources as others might just offer a different stereotype.

- Help disproving them. Armed with knowledge you can now offer the real view and say ‘I disagree, the ABS found that in the last decade the number of Aboriginal students in higher education grew by 20%’.

After experiencing Aboriginal culture first-hand for 4 weeks during the series First Contact, Bo-dene Stieler realised her false beliefs:

“Before the journey, I would never have thought that my biggest life inspiration would come from Aboriginal people. Looking back, I can’t believe the ignorance I showed and the disrespect I showed by not even taking the pro-active approach to find out more and just believing everything that I had been told.” [19]

I never realised that I would share so many connections with Aboriginal people. I always thought that there was some huge divide that could never be crossed. But I was wrong.

— Bo-dene Stieler, participant in First Contact [19]

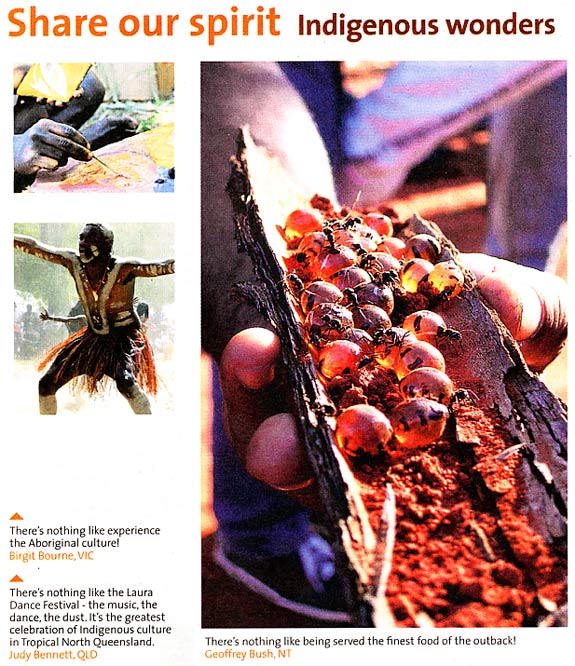

‘Good’ stereotypes: Australia’s tourism industry

Stereotypes don’t need to be bad. The tourism industry of Australia relies heavily on the stereotype of an ancient and mythical Aboriginal Australia to sell its products.

In the history section the website stops to tell about Aboriginal people beyond the 1967 Referendum. The ‘Culture’ section refers to the Bangarra Dance Theatre’s style as ‘traditional’ whereas it is, in fact, also very contemporary.

The tourism industry has perfected the art of creating the good stereotype in the minds of readers of their promotional material without saying anything that’s untrue.

Read the following extract of a text by Tourism Australia which appeared in a German newsletter about Australia [21]:

The Aborigines of Australia are the keepers of one of the oldest existing cultures. They are proud of their culture and traditions. They love to share their traditional music, ritual dances and knowledge about their land. Tourists who let themselves into meeting Aborigines during a tour into the outback can visit unique places, sense the spirituality of ancient customs, experience the spectacular nature or get close to how these people live during a stay in an Aboriginal community. You meet Aboriginal art and culture everywhere in Australia. If along the coast, in the heart of Australia or even at Circular Quay in Sydney or the Botanic Gardens of Melbourne - Aboriginal art and culture is present in the entire country. Tourists have many options to experience it. In urban regions, for example, galleries and exhibitions offer views into contemporary Aboriginal Australia.

View the original German text

Show

Die Ureinwohner Australiens sind die Hüter einer der ältesten noch bestehenden Kulturen. Die Aborigines sind stolz auf ihre Kultur und Traditionen. Ihre überlieferte Musik, ihre rituellen Tänze und ihr Wissen über ihr Land teilen sie gerne mit Besuchern. Touristen, die sich auf die Begegnung einlassen, sehen bei Touren im Outback einmalige Plätze in Australien, spüren die Spiritualität der uralten Bräuche, erleben die spektakuläre Natur oder erfahren bei einem Aufenthalt in einer Aborigine Gemeinde hautnah die Lebensweise der Menschen.

Auf die Kunst und Kultur der Aborigines trifft man überall in Australien. Ob entlang der Küste, mitten im Herzen Australiens oder sogar am Hafen von Sydney oder in den Botanischen Gärten Melbournes - die Kunst und Kultur der Ureinwohner ist im ganzen Land präsent. Touristen haben viele verschiedene Möglichkeiten, sie zu erleben. In urbanen Regionen etwa bieten Galerien und Ausstellungen Einblicke in das zeitgenössische aboriginale Australien.

Wouldn’t you agree that you just saw a fur-clad Aboriginal person holding a spear and boomerang?

Analysing the text we find words and attributes such as ‘keepers’, ‘oldest’, ‘traditions’, ‘ritual’ and ‘ancient’. The text serves the stereotype of Aboriginal people ‘living a traditional tribal/ancient lifestyle’ mentioned earlier. It’s all in the words. ‘Contemporary’ is only mentioned in conjunction with galleries and exhibitions.

95% of Australian tourists want to experience Aboriginal culture during their trip and that’s why Tourism Australia has chosen to feature the image of an Aboriginal tour guide prominently on their website (see image above). But I have to disappoint you.

Many Aboriginal people struggle to get jobs, even in the tourism industry. Some Aboriginal people might not even know about their own culture, have lost their family ties or don’t practise any traditional customs at all.

We don't practise our Aboriginal culture much because my nanna was stolen when she was eight years old and put in a dormitory and required to work for a white couple, so we're missing a part of our ancestry.

— Stephen Pitt, Sunshine Coast, QLD [22]

Stephen’s nanna was ‘stolen’ because she is a member of the Stolen Generations, Aboriginal people who were taken away by the Australian governments “for their better” and to be trained as domestic servants or workers.

Here is another example for a ‘good stereotype’, also by Tourism Australia:

What tourist advertising does not tell

Australian tourists want to be served the good stereotypes of Aboriginal Australia. Imagine what would happen if we told them the truth about the contemporary situation Indigenous people are in:

The text on the left hand side is taken from Tourism Australia’s website australia.com in 2008 [24]. Next to it I’ve put my version, written with the background of more than a year’s study of Aboriginal affairs by reading the National Indigenous Times and Koori Mail. I don’t want to discredit australia.com, but show how different a picture you can get if you read elsewhere.

| What the tourist industry says [24] | What the news tells us | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | “You’ll transcend your five senses when you see Australia through the eyes of its first inhabitants. For Aboriginal people, ‘country’ is not just a collection of hills, cliffs, creeks, rock outcrops and waterholes. It is a magical network of land and living things, elements and seasons, Dreamtime stories, spirits and songs.” | You won’t believe your five senses when you see Australia through the eyes of its Aboriginal people. For Aboriginal people, ‘Australia’ is not just a collection of obstacles, racism, neglect, ignorance and ill-information. It is a magical maze of bland, unforgiving things, elements and treasons, disappointing stories, alcoholic spirits and deaths. |

| Verify it: Racism | Discrimination | Alcohol consumption | Life expectancy | ||

| 2 | “This is the land that Aboriginal people have lived in harmony with for more than 50,000 years. Every river, tree, mountain, star and sandy hill was shaped by a spirit ancestor during the Dreamtime of the world’s creation. Listen to these stories and you’ll begin to understand the birth of our land, its cragginess, spirituality and mystery. Visit the sacred places and feel your own sense of wonder come alive.” | This is the society that Aboriginal people have lived in struggle with for more than 200 years. Every river, tree, mountain, forest and resource was acquired by a white man during the invasion time of the white nation. Listen to these stories and you’ll begin to understand the birth of their struggle, disadvantage, hopelessness and sickness. Visit the sacred places and feel your own sense of wonder why they’re not protected. |

| Verify it: Land | Health | Spirituality | Pilbara strike | ||

| 3 | “Trace the path of spirit ancestors as you walk around the base of Uluru with an Anangu guide. Learn about the intricate system of life they created in the rock art of World Heritage-listed Kakadu National Park. See Ngunawal campsites dating back to the last Ice Age in Namadgi National Park. Go walkabout and see bark and body painting in the Blue Mountains, just outside of Sydney.” | Trace the path of white ancestors as you walk on top of Uluru without any Aboriginal consent. Learn about the intricate system of disrespect whites show towards the rock art of not only Kakadu National Park. See construction worker’s campsites and toilets built over sacred sites. Go walkabout and see how bark and oil paintings are sold without passing on their revenue to the artists just outside of Sydney. |

| Verify it: Rock art | Art profits | Toilet on sacred site (and [25]; see also sidenote below) | ||

| 4 | “Hear Adnyamathanha creation stories over the campfire in South Australia’s Flinders Ranges. Trace Aboriginal trading routes more than 18,000 years old in Victoria’s Gippsland. Fish, snorkel and hunt for mud crabs with the Aboriginal communities of Western Australia’s Dampier Peninsula. Traverse the treetops with the Wujal Wujal people in Queensland’s primeval, magical Daintree Rainforest. Discover your own story in amongst this ancient, living story of creation.” | Hear massacre creation stories over the campfire near South Australia’s Rufus River. Trace Aboriginal fights for fair wages of over more than 500 million dollars in New South Wales. Hunt for Aboriginal rock engravings destroyed by gas and mining industries on Western Australia’s Dampier Peninsula. Traverse the broken family lines of Aboriginal people in Queensland’s brutal mission history. Discover your own point of view in amongst this ancient fog of tourist advertising. |

| Verify it: Massacres | Stolen wages | Dampier Peninsula rock art | Stolen Generations | ||

Sidenote: On 10 January 2011, the Supreme Court of Australia dismissed an appeal against a $500 fine imposed on the company who had built the drop toilet on sacred ground in November 2007. Under Northern Territory Intervention laws, evidence should have been presented citing the “detrimental effect of the desecration”. The sacred site is considered ceremonially significant to many clans in the region of Arnhem Land, and is used several times during the year by local Aboriginal men and women. [26]