Health

Aboriginal life expectancy

Aboriginal health standards in Australia let almost half of Aboriginal men and over a third of women die before they turn 45. At all ages, Aboriginal life expectancy is lower than for non-Aboriginal Australians.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

Selected statistics

- 71.6

- Life expectancy at birth for Aboriginal males in Australia. [1]

- 75.6

- Life expectancy at birth for Aboriginal females in Australia. [1]

- 8.6

- Number of years Aboriginal Australian males die earlier than their fellow Australians. [1]

- 7.8

- Number of years Aboriginal Australian females die earlier than their fellow Australians. [1]

- 60.2

- Median age of Aboriginal people at death in 2018, up from 55.8 years in 2008, 21 years less than for the Australian population as a whole. [2]

- 87.7

- Projected life expectancy for men at birth in 2050. Same figure in 2008: 79, in 1998: 76.

- 90.5

- Projected life expectancy for women at birth in 2050. Same figure in 2008: 84, in 1998: 82.

-

80% - Percentage of the life expectancy gap attributed to chronic diseases such as heart disease (22%), diabetes (12%) and liver disease (11%). [3]

- 40..49

- Age where mortality rates for Aboriginal males are around 4 times higher than rates for non-Aboriginal males. The same rate applies for Aboriginal women aged between 30 and 39. [1]

- 9.1

- Age-standardised death rate in 2018 for Aboriginal people living in NSW, QLD, WA, SA and the NT. [2]

Average Aboriginal life expectancy

Aboriginal people can expect to die about 8 to 9 years earlier than non-Aboriginal Australians. On average, Aboriginal males live 71.6 years, 8.6 years less than their non-Aboriginal peers, women live 75.6 years, 7.8 years less. [1]

Compared to figures ten years earlier this is an improvement. Back then, males lived on average 67 years (11 years less) and females 73 years (10 years less). [4]

Aboriginal life expectancy is so low because Aboriginal health standards in Australia let 45% of Aboriginal men and 34% of women die before the age of 45. About 71% die before they reach the age of 65. [5]

When considering life expectancy remember that it differs regionally. Life expectancy at birth is highest in Queensland (74 years) and lowest in the Northern Territory (67.5 years). [1] While the median age at death is 57 years in New South Wales, the highest for any region in Australia, in Western Australia the median age is just below 50 years. [6]

Life expectancy also varies between urban and (very) remote areas. In major cities it is about 74 years, in remote and very remote areas about 68 years. In the latter regions the gap is also larger – about 14 years. [1]

Hence, to properly consider Aboriginal life expectancy statistics, you need to consider the data for your region of interest.

Also, life expectancy changes as you age. It is largest at birth – your whole life is ahead of you – and continuously declines until you die. If not indicated otherwise, life expediencies shown here are those at birth. For age-specific rates, check the sources.

In an analysis of the health of indigenous peoples worldwide, the United Nations singled out Australia and New Zealand as countries that "are struggling to close substantial gaps between indigenous and non-indigenous populations in life expectancy". [7]

I always say that when we lose an old person, we lose a library… language and culture.

— Lola Forester, Aboriginal radio presenter [8]

Story: Grief, overwhelm and urgency

Tiwi man and Logie-winning actor Rob Collins reflects on how a lower life expectancy makes him feel:

"I’m just like anyone: I want a rich life filled with family. The idea that I won’t have that with a lot of my family members? I feel overwhelmed by that.

"Yes, we’re addressing health and education outcomes for Aboriginal people, but the mortality rate isn’t slowing. I have this overwhelming sense that change will come too slowly.

"And by the time we have increased life expectancy and closed the gap, I will have lost a lot of my family members. It’s a mixture of grief, being overwhelmed and a sense of urgency.

"I want my kids to learn the language and culture because there’s only a finite amount of time for them to do it. Once that opportunity is gone, it’s gone." [9]

Comparing Aboriginal life expectancy is difficult

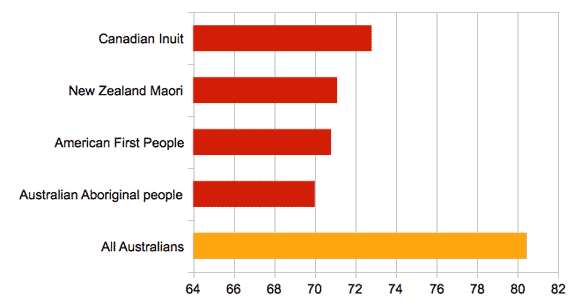

Comparing Aboriginal life expectancy across countries is notoriously difficult. Each country has different methodologies how it counts its indigenous citizens. Australia estimates figures based on self-identification, New Zealand by ethnic group membership, the USA if people live on or near reservations, and Canada counts "Registered Indians".

Consequently, it is difficult to justify drawing many conclusions regarding cross-country differences.

The following comparison is based on data published by Bramley et al. in 2004. [10] Bramley evaluated data from 2000–2002.

The average life expectancy of Australian Aboriginal people is 59.5 years and has remained steady between 1990 and 2000. [11] American Indians and Alaskan natives lived an average of 70.8 years over that period. Canadian Aboriginal people lived an average of 72.8 years, Maoris 71.1 years.

Newer data calculated by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) yields a smaller gap between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal life expectancies. This is because in 2008, the ABS has introduced a new method for calculation. While the underlying method to process the data remained the same, the method for accounting for under-identification of Aboriginal deaths changed.

Using this new method, the average life expectancy for Aboriginal people is 70 years. [4]

Why live Aboriginal people shorter lives?

Causes for a low life expectancy include:

- poverty,

- poor health and nutrition – about 80% of the life expectancy difference is due to preventable chronic conditions, such as heart disease, diabetes, chronic lower respiratory diseases and lung and related cancers; [2]

- poor housing,

- dispossession of their traditional lands,

- low education level,

- high unemployment,

- hidden racism, and

- inability of politicians to address Aboriginal problems.

We are still living in pain and trauma. We are in pain already and more and more pain is falling on top of us. It makes us feel weaker and weaker. People are getting sick, tired and stressed.

— Yalmay Yunupingu, Aboriginal artist and teacher [12]

"Adequate primary health care services can bring about dramatic results," says former Social Justice Commissioner Tom Calma. [14]

The life expectancy of native Americans increased by about 9 years, between 1940 and 1950, after such services were provided. The life expectancy of Maori in New Zealand increased by 12 years from the 1940s to the 1960s, attributed to the same reason.

Australian life expectancy figures might be all wrong

While the life expectancy figures presented above are bad news by themselves, the truth might be even worse for two reasons: Statistics differ greatly between states and territories, and undertakers not always record Aboriginal descent properly.

Aggregated data excludes

When data about Aboriginal deaths is collected from different areas and aggregated into one single figure, regional differences get lost. For proper figures, data needs to be disaggregated.

Only if we consider data by each region can we consider what "needs to be done for those whose lives could improve to ensure they do not die at 30 years less than median life expectancy of Australians. When we collectivise data and highlight the overall median we fail people demographically – they become invisible," argues Gerry Georgatos, suicide prevention researcher with the Institute of Human Rights and Social Justice. [6]

Miscounting the dead

According to academics, 50% of death forms filled out by undertakers don't identify if the deceased is of Aboriginal descent or not. [15]

We can't really even track changes to say yes, things are on the way up or no, they're getting worse.

— Prof Tony Barnes, Charles Darwin University

With no accurate statistics on the number of Aboriginal people dying each year it is impossible to calculate Aboriginal life expectancy and any progress on closing the life expectancy gap.

Two estimates of Aboriginal life expectancy in 2008 differed by as much as five years, providing contradictory messages on the magnitude of the life expectancy gap and rendering any mortality rate calculation unreliable. [16]

Hence the Australian Bureau of Statistics had to use a 'semi-theoretical' approach for its calculations and has done so since 1996 because census results are 'unreliable'.

The 20-year life expectancy gap which was identified in 1973 might still be there, but no-one knew for sure or could tell if it has widened instead.

Really, there's no change [of the life expectancy gap].

— Prof Len Smith, Australian Demographic and Social Research Institute

A new methodology to calculate the life expectancy gap

Consequently, in May 2009, the Australian Bureau of Statistics introduced a new methodology to "better compensate for a significant undercount of Indigenous death records". [17]

The new "experimental figures" released by the ABS show the life expectancy gap has narrowed, [18] from previously 20 years to approximately 10 years in 2007 and 8 years in 2017.

A gap of either 10 or 17 years is utterly unacceptable in a country like Australia that prides itself on a fair go for all.

— Tom Calma, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner [17]