Health

Kidney disease among Aboriginal people

When kidneys fail, Aboriginal people are more likely to get dialysis treatment than a transplant.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

Selected statistics

- 10

- Times an Aboriginal person is more likely to have kidney disease. [1] In some remote communities this can be 30..50 times the national average. [2][3]

- 2.8

- Times an Aboriginal person is more likely to die from kidney disease. [4]

-

50% - Proportion of Aboriginal kidney failure sufferers living in regions without any dialysis facilities. [2]

- 5

- Survival rate in years for people with renal failure. [3]

- 120

- Number of new patients with severe kidney failure in the Northern Territory per year. [4]

-

20% - Percentage of Aboriginal adults in Australia who have signs of chronic kidney disease; percentage for the NT: 33%. [4]

-

1.9% - Percentage of Aboriginal people who manage kidney disease as a long-term health condition; proportion of Torres Strait Islanders: 0.4%. [5]

What is kidney disease?

Failing kidneys are one among the many health problems afflicting Aboriginal people.

Smoking, diabetes, poor nutrition, obesity, high blood pressure and lack of exercise are among the causes of kidney failure, also called nephropathy.

Nephritis is inflammation of the nephrons, the functional units (think filters) of the kidney. Nephritis is usually associated with poverty. Outbreaks in Australia mainly occur in remote Aboriginal communities in far northern Australia and affect young children. Health professionals distinguish between chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), a stage when people need either dialysis or a transplant to survive.

Kidney failure is also known as renal failure and the "silent disease" because sufferers can lose up to 90% of their kidney function before they notice any symptoms. [4]

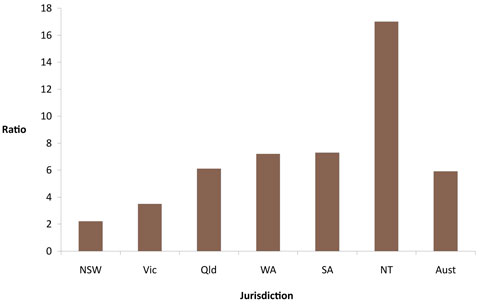

In 2007-2008, almost 10% of ESKD patients treated were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people. [6] A study published in 2013 found that Aboriginal patients were 20 to 30 times more likely to have end-stage renal disease. Some of this research indicated that remote living Aboriginal peoples were more susceptible to nephropathy than those who are urban residents. [7] The researchers also found that urban Aboriginal patients are nearly 7 times as likely as non-Aboriginal patients to enter a high CKD stage.

Renal failure has reached epidemic proportions for Indigenous people in central Australia.

— Dr Paul Lawton, Menzies School of Health Research [4]

How does it affect Aboriginal people?

Kidney problems and failure is frequent among older Aboriginal people (40 to 60 years old). "There is not a family in remote Australia who is not touched by this problem," says Sarah Brown, chief executive of Aboriginal-run community health group Purple House. [4]

In 2017-18, ‘care involving dialysis’ was the most common reason for Aboriginal people to go to hospital. [5]

The reasons for these high rates are complex and likely due to several factors, including increased susceptibility to kidney damage (a genetic predisposition), higher rates of diabetes and obesity, being born prematurely with small kidneys, constant infections, high blood pressure, poor access to good food, substandard housing or limited education. [9][10]

Kidney failure is, ultimately, "an illness born of poverty and dispossession," says Sarah Brown, chief executive of the Purple House dialysis program in Alice Springs. [10]

Most Aboriginal patients endure many years of dialysis as they are deemed unsuitable for transplants due to health and social problems that go hand in hand with their daily life. [4]

Their likelihood to die from kidney disease is more than 15 times that of non-Aboriginal Australians. [11] A prominent victim of the disease is Yothu Yindi lead singer M Yunupingu who died in May 2013.

The population structure in Aboriginal Australia has the shape of a pyramid, with many more children than adults and even fewer living grandparents.

Early deaths of Aboriginal adults from kidney disease, but also diabetes and heart disease, contribute to forming the pyramid.

Mothers with kidney damage can pass on the disease to their children. Aboriginal mothers often have evidence of kidney disease already present during pregnancy, and Aboriginal babies are frequently born with a much smaller number of nephrons.

While non-Aboriginal babies have over one million nephrons, Aboriginal babies have typically around 400,000. [11] As a result, Aboriginal babies are born too small.

Traditionally, kidneys hold the spirit. If you have sick kidneys, you have a sick spirit.

— Sarah Brown, chief executive of the Purple House dialysis program [10]

Treating kidney disease

Only 12% of Aboriginal Australians with treated ESKD have a functioning kidney transplant, compared with 45% of non-Aboriginal Australians. [6]Kidney transplantation usually gives the best rehabilitation at the lowest cost, [13] but because there are not enough donors it is used less than dialysis, the next best option. Hence Aboriginal people are more likely to be on dialysis than to receive a kidney transplant. [6] Matching genetics is another challenge.

Patients need to receive dialysis three times a week, with each treatment lasting 4 to 5 hours, during which their blood is sucked out in one tube, cleaned, and reinserted into the body in another tube.

In 2008-09, 11 times more Aboriginal people went to hospital for dialysis treatment than non-Aboriginal people. [6] Attendance rates for treatment can be poor because it is not easy to let Aboriginal people feel at ease in western hospitals.

Dialysis can be delivered into remote Aboriginal communities but requires cultural training of staff who need to learn to use photographic rather than written instructions, and show respect and avoid naming deceased persons after family deaths.

Patients suffering from kidney disease are not only traumatised because of the illness, but also when they have to relocate vast distances from their homeland to receive life-saving treatment. [14] “It is just not practical or financially possible for people to get back home, many patients have not been able to return home for many years,” says Jimmy Little, founder of the Jimmy Little Foundation which aims at helping Aboriginal sufferers. [2] Another problem is the limited number of dialysis machines which forces some patients to use planes to find a vacant one. [4]

For this reason, the Jimmy Little Foundation offers a Return To Country program.

At Kintore community in the deep desert, where the experts said dialysis would never work, the band of kidney patients trained in the purple [dialysis] house have a perfect 100% turn-up rate.

— The Australian [12]

Financing dialysis

Aboriginal communities use mining royalties, self-funding and philanthropic support to finance dialysis services. [3]

Story: Painting for relief

In the early 1990s the Pintubi people of the Western Desert area tried to get government support for dialysis, but without success.

They formed the Western Desert Dialysis Appeal, and community members painted pictures and sold them through the Art Gallery of NSW, raising $1 million.

With the money raised they set up dialysis machines in Alice Springs and Kintore in 2004, with Kintore having the first dialysis machine in a remote community in Central Australia. [3]

How can we reduce kidney disease?

9 out of 10 ESKD cases could be avoided if Aboriginal people were treated at the same rate as non-Aboriginal people. [6]

Improving access to specialist medical intervention and to various care and treatment education would also reduce the rate of ESKD. [7]

Story: The plan is not to have a plan

Don Palmer is CEO of the Malpa Project which aims to close the gap in Aboriginal health. He remembers learning about the government’s plan in helping lessen Aboriginal kidney failure. [15]

“Some years ago I had the sobering pleasure of travelling around Indigenous communities with Jimmy Little for about three years whilst helping to set up his foundation.

Once when we were travelling together in Alice Springs I met the Northern Territory Health Minister [and] asked what his plans were for addressing the extraordinary incidence of kidney failure.

Kidney failure runs at about 30-50 times the national average out in the Centre.

He said he had no plan.

I mentioned this to Jimmy over breakfast the next day and he said the only hard thing I ever heard him say.

He began with ‘There is a plan’. What is it I asked, eagerly. His reply lives with me.

He said ‘The plan is not to have a plan’.”