Health

Making health services work for Aboriginal people

Simple changes to hospital and doctor's wards make Aboriginal people feel welcomed, at ease and improves their chances of recovery dramatically.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

Selected statistics

- 204

- Number of Aboriginal doctors in Australia in 2014 [1]; same figure in 2010: 140. [2]

-

1% - Percentage of trainee GPs in Australia that are Aboriginal (34 people out of 3,554). [3]

- 928

- Number of Indigenous doctors Australia needs to close the gap in Indigenous health outcomes. [2]

-

60% - Percentage of Aboriginal people who go to a doctor or GP outside of Aboriginal Medical Services and hospitals. [4]

- 150

- Number of Aboriginal community-controlled health services in Australia. [2]

- 1,000

- Number of Aboriginal health workers employed across Australia in August 2012. [5]

- 1,500

- Number of Aboriginal health workers needed across Australia to access all patients in need. [2]

-

25% - Percentage of Aboriginal parents who could not name a usual doctor. Same rate for non-Aboriginal parents: 10%. [6]

- 230

- Number of Aboriginal midwives in Australia in 2015 (about 1% of the total midwifery workforce) [7]

- 1.5

- Times Aboriginal patients are more likely to leave hospital before their emergency treatment because they don't feel comfortable. [8]

Overcoming broken trust & deep-seated suspicion

For many Aboriginal people being in a sterile hospital environment conjures up memories of racism and mistreatment. Many Aboriginal people have a lot of mistrust towards the existing health system [9][10] due to their past and present experiences with mainstream services.

Aboriginal patients feel reluctant to navigate an "unfamiliar" health system that might treat them in an "unfriendly" way, especially if they don't follow expected rules, such as being on time. [10]

"Because of the history, there's a lot of distrust in regular health services," says Aboriginal woman Stacey Foster-Rampant. "So if they don't feel comfortable with them, they won't use them." [10]

Some fear they will never leave a hospital alive. "For many Aboriginal people in the bush, hospital is code word for 'the place you go to die'," says a resident from Mataranka in the Northern Territory. [11] "People are used to seeing friends and relatives go off to hospital but never coming home. For them it seems that agreeing to go to hospital means agreeing their life is over. They won't do it while they are conscious."

Hospital is code word for 'the place you go to die'.

— A resident of Mataranka, Northern Territory [11]

Many members of the Stolen Generations are "deeply traumatised" [10] and choose not to see a white doctor or only when their condition has severely deteriorated. For example, only 67 Aboriginal adult health checks were performed in an area in Queensland with more than 12,000 Aboriginal residents. [12] Less than 0.6% had their health checks done.

Aboriginal people don't trust non-Aboriginal nurses and midwives because they were integral to the policies that created the Stolen Generations. [7]

Alice Smith, a Punjima woman from Western Australia, remembers: "I didn't want to have my kids in hospital because the doctor is a man. Out in the bush you don't have anyone. The mother got to sit down by herself, and a woman is there just to help… None of the women used to go to the hospital. I used to have bush medicine all the time. If they get sick we know what tree to get, and to boil it or whatever we needed to do… I grew up in the bush and never had a tablet to fix me." [13]

This is what works

For a medical environment to work for Aboriginal people it needs to overcome the barriers they perceive. Offering flexible and culturally appropriate care is vital. Good solutions include:

- Employ Aboriginal doctors, nurses, midwives and staff. The number of Aboriginal patients attending a clinic increased "markedly" following the arrival of an Aboriginal doctor. [14] "There is an element of difference when you have an Aboriginal face on the other side of the table," says Aboriginal eye doctor Dr Kris Rallah-Baker. [1] "Having Indigenous midwives sends the message that this is a culturally safe environment and ultimately women will be more likely to access that service," agrees Janine Mohamad, CEO of the Congress of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Nurses and Midwives. [7] And it works for patients who "build a bond" and "feel safe" with them. [10]

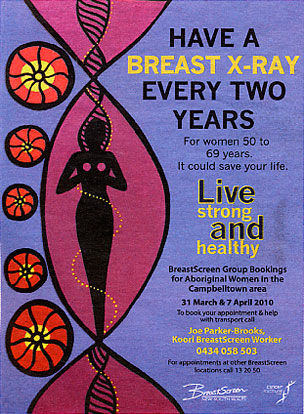

- Create an Aboriginal-friendly feel. Displaying Aboriginal artworks [15] helps Aboriginal people relax and connect with the place. Aboriginal artwork on the outside of an ambulance also helps Indigenous communities develop a sense of pride and ownership in the vehicle [16]. Images showing Aboriginal patients indicates "this is referring to me" to Aboriginal people. [7]

- Offer culturally appropriate alternatives. 'Birthing on Country' has little to do with going bush and digging a hole. Instead, it's about offering Aboriginal women a place of their own, a birthing centre with Aboriginal governance and continuity of care within the community. [7]

- Help Aboriginal patients understand their disease. Many are uncertain about what has caused their condition [17]. Use clear, simple language with fewer words and more pictures [18]. Computer-animated movies employing three-dimensional Aboriginal characters talking in patient's native languages have "revolutionised" the delivery of critical health messages [19].

- Verify informed consent. For traditional Aboriginal people 'informed consent' for medical procedures must come from the 'right' person within the network of kinship and community relationships, not necessarily solely the patient [20]. Disrespect for such a process might lead to payback for the ill person.

- Offer culturally appropriate materials. Culturally appropriate material includes maternity books and diaries designed for Aboriginal people.

- Inform Aboriginal patients in their own language. This way they can better understand potential harms or benefits of the procedures offered [20].

- Provide medical dictionaries. They help improve communication between health professionals and Aboriginal patients.

- Communicate well. While the Western approach looks at health from a biological perspective, Aboriginal people often have a more holistic approach to looking at health [9]. Take time to build a rapport with patients, take a thorough history and give them the space to open up. [7] Sometimes this might mean to follow up with someone who missed an appointment and visit them at home instead. [10]

- Have culturally aware staff. Train them in Aboriginal culture so they can offer respect and understanding. For example, Aboriginal men are reluctant to admit their ill health, particularly in front of women. Aboriginal patients might show up late because they had to tend to a family member who dropped in and they have an obligation to spend time with them. [10] Aboriginal health workers "have got to cultural events" and visit Aboriginal medical services "for absolutely no reason" to build and maintain connections to, and trust with, the community. [21]

- Act culturally appropriate. For example, a woman might not feel comfortable being treated by a male health professional. If people identify with the setting it allows them to socialise with others and access information in a non-threatening and comfortable way. Men might need back door entrances to encourage their attendance and separate them from women.

- Offer low price treatments. Many Aboriginal patients have a low or no income.

- Aboriginal healing garden. When the Royal Adelaide Hospital underwent refurbishment the design included an Aboriginal Health Garden. Its walls feature designs by Kaurna artist Karl Telfer and Ramindjeri artist Sam Gollan. The designs tell stories of local history and seek to reinforce the idea that the garden, located near the entrance to the Aboriginal Health Unit, is for contemplation and healing.[22]

- Minimise stereotyping. Women, for example, are "constantly" battling the stereotypethat they are in an abusive relationship.

- Facilitate transport. Transport is "one of the key things" that prevents Aboriginal patients to visit a GP, and not only in remote areas. People might struggle if they have many children to look after or transport is private, inconvenient, slow and expensive. Health service might work better when it comes to the people instead. [21]

- Clinics need stable funding. Governments need to provide reliable funding for Aboriginal medical services so they can maintain the programs and solutions they developed for their communities. [21]

NSW Health recognised the need for Aboriginal-specific areas in hospitals and in 2018 updated its statewide policy to include guidelines on providing "culturally appropriate spaces" for Aboriginal patients and families. A prior trial had shown a 50% reduction in the number of Aboriginal patients leaving early from emergency departments after cultural awareness training for staff was introduced. [8]

After the introduction in 2006 of Malabar Midwives, an Aboriginal health care service, the number of Aboriginal women giving birth at the Royal Hospital for Women in Randwick, NSW, tripled. [10]

Story: How Aboriginal parents won the vaccination race

When it comes to vaccinating children there is much talk about 'herd immunity', meaning a high enough percentage of children of a particular age group are vaccinated. Often this percentage is considered to be around 95%.

In the early 2010s non-Aboriginal parents in the Hunter New England region (about 150 kms north of Sydney) had reached herd immunity (94%) while Aboriginal parents lagged behind by 8%, putting their children at risk.

A local Aboriginal health service knew that in order to attract parents to vaccinate their children they had to employ Aboriginal staff who knew their community. Aboriginal patients trust them more, and often would pass on resources they received to their families.

The service's decision triggered a massive change. By 2015, 91% of one-year-old and more than 95% of 5-year-old Aboriginal children were vaccinated.

It led to the NSW Ministry of Health adopting their program and reaching targets years ahead of the scheduled goal. [21]

Video: Supporting patients in hospital

Aboriginal patients don't complain, they stay away

When Aboriginal people have bad experiences with health services they stay away and don't complain. [23]

Experience, and fear of racism is the biggest barrier to Aboriginal people speaking up. They are also worried that if they did speak up they could make things worse.

If Aboriginal people delay going to a hospital they get there being sicker and should get treatment that considers their condition. But this is not necessarily so—prejudice and discrimination not only change the sort of treatment they receive, it also makes them feel feel unwelcome, uncomfortable, not deserving or prejudged.

There are "lots of scenarios" of Aboriginal people being considered to be seriously intoxicated when in fact they've been seriously ill. [24]

If Aboriginal people were invited and supported to give feedback they would most likely to do so, preferably to an Aboriginal contact person.

My nanna was 12 when her mother died because she didn't trust white doctors…

— Dr Kris Rallah-Baker, Aboriginal eye doctor [1]

Story: "He came out with tears in his eyes"

Aboriginal singer/songwriter Archie Roach tells the following story [25].

"I remember one time when one old uncle went along to a health service. He came out with tears in his eyes and I said 'Are you right, Unc?'

"He said, 'I'm just so happy that I was treated today by an Aboriginal doctor… I never thought I would see the day.'"

Sister Bush

Sister Alison Bush was the first Aboriginal nurse to be based at a major metropolitan hospital in NSW. She was known as a "cultural broker" between Aboriginal women and the health system, ensuring they were cared for in a respectful, safe and secure way [26].

A friend and doctor, Robyn Shields, says "Alison witnessed the birth of generations. She had a healing [influence] and just knowing she was at the hospital was a comfort."

Sister Bush became a midwife in 1966 and worked at Royal Prince Alfred hospital from 1969 until her death in October 2010, aged 68.

There is a substantial body of research evidence indicating that the development of a skilled and professional Indigenous health workforce is an essential prerequisite for improvements in Indigenous health.

— Dr Mick Gooda, CEO Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health [27]

Story: How Prof Noel Hayman transformed his practice

Aboriginal Associate Professor Hayman practices at the Inala Health Clinic in Brisbane, Queensland.

To make the clinic more attractive to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients he employed more Indigenous staff and saw that cultural-awareness programs were provided for all staff [29].

Prof Hayman changed the environment at the clinic to a more welcoming and culturally appropriate by hanging Aboriginal paintings.

The result: Patient consultations increased from around 1,600 per year in 1996 to over 12,000 in 2008.

Health improving in some areas

An Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) report highlights the fact that health trends among Aboriginal people are improving in many areas [30].

This is particularly important as a majority of the 100 health services whose data was reviewed were Aboriginal community-controlled.

The report found that between 2008 and 2011:

- Birth weight increased. The proportion of babies with normal birthweight rose from 80.0% to 84.2%, while babies with low birth weight dropped from 15.2% to 13.5% between 2008 and 2011 and average birthweight rose from 3,015 grams to 3,131 grams.

- Pregnant women consumed less alcohol. Alcohol was consumed by 17.9% of women in the third trimester of pregnancy in 2011—a drop from 21.4% since 2008.

- Smoking among pregnant women was stable. Among mothers, there was a very small drop in the proportion who smoked during the third trimester of pregnancy—from 53.4% to 52.4%.

- More people managed their chronic diseases. Increases were seen in the proportions of people with chronic diseases such as diabetes and coronary heart disease who had a GP management plan as part of their treatment. The proportion of clients who had an MBS GP management plan rose from 24.8% to 31.6% of people with Type 2 diabetes between 2008 and 2011 and from 22.9% to 33.4% for people with coronary heart disease.

- People had more tests. The proportion of people with Type 2 diabetes who had a blood pressure test in the last 6 months increased by nearly 10 percentage points from 52.7% to 62.3%.

Traditional Aboriginal healing

Marjorie Parker comes from the Pilbara region in north-west Western Australia where she has been working as an Aboriginal nurse. She explains that some Aboriginal patients request the services of traditional healers, the Ngangkari[31].

"In hospitals they should have Aboriginal videos, playing culture for the people. There is nothing for Aboriginal patients to make them feel supported in the cultural, spiritual being. The hospital staff don't take into account the spiritual well-being of the Aboriginal patients. It's all medical treatment. Sometimes you need to go further."

"Some patients have requested treatment from their own culture, from medicine men. Hospitals do not recognise the legitimacy of treatment that traditional healers can give and this is wrong. They think it is voodoo stuff."

Once hospitals do open up to traditional Aboriginal healers, appointments and attendance rates can skyrocket, and it's a chance for other staff to learn how the healers make the hospital space more culturally acceptable. [32]

Traditional healer Gerry Bostock feels that the focus in Aboriginal healing needs to shift away from drug and alcohol abuse to deeper issues such as trauma and dispossession and the lack of role models for children [33]. People acknowledge "the need for traditional Aboriginal healing and alternative medicine to foster individual and cultural renewal," he says.

Story: The old lady who wanted to go home

Aboriginal nurse Marjorie Parker recalls the story of an old lady who wanted to go home, against the doctor's orders [31].

"One time an old lady, who didn't appear to be very sick, but felt that she wasn't going to last the night, wanted to go home to her family. She was just wailing and wailing.

I said to the sister, 'We can't keep her here, it's cruel we must send her home.' The sister said, 'But the doctor's orders are to keep her here.' And I said, 'Yes, but the doctor is [400kms away] in Exmouth and this poor patient only wants to go home and be with her family. I believe that she spiritually feels that she is not going to survive the night.'

I thought that if this is what she believes then she is entitled to be with her family and to die wherever she wants to, not in this environment.

I said to the sister, 'I must go to Bindi Bindi village and see the relatives.' […] So I got the orderly [hospital attendant] and took her home. She was very breathless and life was dim. Yet she spent the evening with her family and passed away that night.

This is but one example of the cultural-based requirement of nursing and caring for Aboriginal patients.

Limited access to doctors in remote communities

Only 20% of Aboriginal people who live in remote communities of more than 50 people have access to a doctor on a daily basis according to Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) figures from 2006 [34]. A further 41% have local access to a doctor once a week or once a fortnight.

But 3% could only see a doctor in their own community once a month, the ABS found. 25% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in communities are 100km or more from the nearest hospital [14].

The ABS estimated 18% of Australia's Aboriginal people live in a discrete Indigenous community (a geographic location, bounded by physical or legal boundaries), most of which are considered remote. Only 10% of them lived in a community with a hospital.

Although more than 140 community services across Australia provide health care to remote Aboriginal populations, less than 50% of these clinics have medical coverage [35] due to a shortage of doctors.

For Aboriginal people living in remote areas access to pharmaceuticals is usually limited due to a lack of infrastructure [9].

The presence of an Indigenous doctor was the main draw for Indigenous people [to access health services].

— Report on Government Services finding [14]

Experiences of Aboriginal doctors

The Australian Indigenous Doctors' Association (AIDA) has published a rare resource called Journeys Into Medicine. It is a book in which 15 Aboriginal doctors and five medical students reflect on what it means to be an Aboriginal person balancing the demands of a Western, bio-medical system while remaining faithful to Aboriginal culture, family and community.

They tell about their challenges and their triumphs. Their careers before medicine and the experiences within medical schools and within the medical profession are as different as the stories themselves.

Journeys Into Medicine aims to challenge stereotypes about the standing of Indigenous people in Australia's workforce.

The book is of special value for high school students contemplating their future and university students studying within medical schools.

The book can be downloaded for free at www.aida.org.au.

Fact Prof Helen Milroy from Wintrop, WA (near Fremantle), is Australia's first Aboriginal doctor [36].

Child doctors succeed where governments fail

A Young Doctor program bridges the gap in some of the poorest communities across Australia by teaching children hygiene, first aid and bush medicine [37].

They are learning to be a Dhalayi (child) doctor at St Joseph's Primary School in Kempsey, NSW. As they are becoming ambassadors for better health the children are nagging parents and friends to keep themselves and their homes clean, smoke outside, buy healthier food, blow their noses properly, urging them to get medical help and helping them navigate the local hospital and health system.

Inspired by traditional Aboriginal medicine, where holistic healers would train children as young as four, the program is successfully running since 2012. It helps children use simple techniques, such as hand washing and proper nose blowing which can prevent infections that cause hearing loss and blindness.

It also addresses the fear many Aboriginal families have of visiting doctors and hospitals. Government programs addressing this fear have made little impact. [37]

Parents, pupils and teachers said the children loved the course, contributing to a near 100 per cent school attendance, unheard of in Aboriginal education.

Using traditional Aboriginal art to explain good health

Doctors in Australia's Northern Territory have found an amazingly obvious way to teach Aboriginal people about diseases and good health [38].

They use paintings produced by local Aboriginal people in Oenpelli's Health Clinic, near Kakadu National Park (about 300km east of Darwin). The paintings encourage patients to participate in discussions about body systems, especially when patients realise that the paintings have been produced by their uncles and cousins.

Aboriginal people are able to identify immediately that the paintings were from the area and painted by people they know. Due to a life's experience of hunting animals for food many Aboriginal artists have a better knowledge of anatomy than mainstream doctors [38].

[Health paintings are] a perfect starting point to build the doctor-patient relationship.

— Hugh Heggie, GP, Oenpelli Health Clinic [38]