Health

Aboriginal smoking: a serious health problem

From a history of being paid with tobacco, smoking rates in Aboriginal communities are declining but way above average, posing a serious health threat.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

Selected statistics

-

37% - Percentage of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders aged 15 years and over who smoked in 2018-19; [1] Same figure for 2015: 44%; [2] for 2002: 49%; [3] for 2005: 54%. [2] About 17% of all Australians smoke.

-

34% - Rate of Aboriginal adults smoking in 2009 in NSW (all Australians: 17.2%). Same figure for 2005: 43.2% (18.4%). [4]

- 2.2

- Times higher: The probability that Aboriginal people smoke tobacco, compared to non-Aboriginal people. [5]

-

54% - Percentage of Indigenous adults who smoke cigarettes, which can be as high as 70% in some northern communities. [6]

-

20% - Percentage of Aboriginal adult deaths in the Northern Territory linked to smoking. Same figure for hospital admissions: 3%. [7]

-

90% - Proportion of Aboriginal prisoners who smoke. [8]

- 147

- Number of cigarettes an Aboriginal person smokes each week. Same number for a non-Aboriginal person: 101. [5]

-

12% - Proportion of sickness and bad health caused by smoking. [9]

- 3

- Times higher: The prevalence of smoking-related cancer in Aboriginal communities, compared to the rest of the population. [9]

-

40% - Proportion of smokers in some Aboriginal communities who are unaware of quit aids. [10]

-

70% - Percentage Aboriginal people are more likely to die from lung cancer than non-Aboriginal Australians. [11]

- 2

- Number of Aboriginal Australians diagnosed with lung cancer every day. Lung cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in Aboriginal people. [11]

-

12% - Share smoking has of all illnesses in Aboriginal communities. [12]

Smoking a serious problem in Aboriginal communities

Statistically the next death through smoking occurs in

Smoking rates across Australia continue to decline, and so does Aboriginal smoking, but Aboriginal people smoke at higher rates.

The proportion of adults in Australia who smoke daily decreased from 24% in 1995 to 14% in 2014-15, a rate which since has been relatively steady (it was about the same in 2017-18). [13]

The percentage of Aboriginal people who smoked has steadily decreased from 54% in 2005 [2] to 37% in 2018-19. [1] However, rates in some communities have been as high as 80%. [14]

Aboriginal people begin smoking at a younger age and are less likely to successfully quit smoking than non-Aboriginal people. [15] But between 2004-05 and 2018-19, the highest reductions in daily smoking have been found in the younger age-groups (18-34 years). [1]

Many health workers, before heading off to see Aboriginal people, stand around their four-wheel-drives "having a puff". [16]

The good news is that Aboriginal smoking rates have dropped an average 2.1% per year since 2008, with particular reductions among young people. [12]

Tobacco isn't always perceived by community members to be a high priority when they are dealing with a wide range of health issues—it is the silent killer.

— Jan Robertson, researcher, James Cook University [10]

Smoking is the number one cause of chronic conditions and diseases among Aboriginal people [17] with lung cancer the second largest cause of premature death. Once diagnosed with lung cancer, only one in three Aboriginal men and one in two Aboriginal women will survive it because they are often affected by other chronic health problems, are diagnosed too late or have less access to treatment and screening [2].

Smoking causes 20% of deaths in Aboriginal communities [18]. More Aboriginal people will die from tobacco-related illness than from alcohol, petrol sniffing, domestic violence and car accidents combined [19].

East Arnhem Land, in Australia's Northern Territory, has the highest per capita rate of lung cancer in Australia [7] which prompted the local Aboriginal health service to start Yaka Narali, an action plan which translates to 'no smoking' in Yolngu language. Between 75 and 85% of people smoke in that area [7].

Smoking can sometimes be traced back to contact of Aboriginal communities with outside cultures which made it become a "normal part" of their culture. Song lines and dances exist in Arnhem Land about smoking with the Maccassans long before white settlement [7]. During white settlement many Aboriginal people were 'paid' in tobacco, further entrenching the habit into their culture.

Each year, 31 May is World No Tobacco Day.

Many pregnant Aboriginal women smoke

This high smoking rate is one of the reasons why Aboriginal infants are six times more likely to suffer a sudden unexpected death than non-Aboriginal children. [21]50% of Aboriginal mothers smoked during pregnancy, a rate that's relatively steady between 2001 and 2009. [22] Since 2009, this proportion has decreased to 44% in 2017. [1] Only 14% of non-Aboriginal mothers smoked in 2009, [22] but 30% did in 2016. [23]

Some young mothers smoke because there are fewer and fewer Aboriginal elders offering help and advice, due to a shortened life expectancy[24]. "[This] eliminates the sense of belonging, ancestry and identity for many young Indigenous peoples which contributes to the rising rate of teenage pregnancy amongst the Indigenous community," explains Caroline Djajadikarta, a Sydney University medical student [24].

Many of the young mums have to cope with depression and anxiety, and use smoking as a means of managing adversity.

Female smokers put themselves at risk of developing lung cancer but also cancer of the cervix because viruses present in the cervix are no longer cleared by the body. Regular pap tests are essential to protect against developing cervical cancer.

When pregnant women smoke, they inhale carbon monoxide, which reduces the amount of oxygen their baby receives and in turn causes a trail of health problems even before it is born: [25][26]

- Ear problems. Examples include an increased risk of 'glue ear', which causes hearing loss, learning problems and behavioural problems;

- Lung problems. Children have a greater risk of asthma and bronchiolitis, followed by chronic lung disease in adulthood;

- Early smokers. These children are more likely to become smokers themselves. Some try smoking as young as five years old.

- Heart attack or stroke. The risk of a heart attack or stroke increases as they grow up;

- Coronary disease. They face a 10 to 15% higher risk of developing coronary disease as adults.

Why Aboriginal people smoke

There are so many Aboriginal smokers because

- Not informed: Aboriginal people don't identify tobacco smoking as a health issue.

- Anti-smoking campaigns fail to reach Aboriginal people because such campaigns need to be developed at 'ground level' for Aboriginal people and by Aboriginal people themselves [14][17]. Many Aboriginal people don't watch TV ads or cannot read magazine ads [17].

- Tobacco payments: Aboriginal people used to get paid in tobacco during their work on white stations.

- It is hard for children to avoid passive smoking in overcrowded houses.

If we could reduce tobacco consumption levels in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community to what it is in the general population we could increase life expectancy by between 4 and 5 years.

— Warren Snowdon, Indigenous Health Minister [17]

Homework: Reaching Aboriginal people with anti-smoking messages

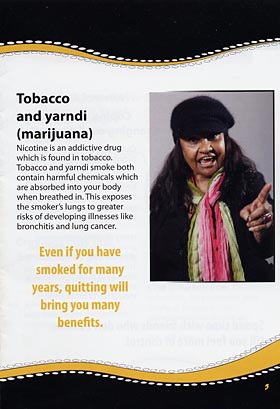

Check out the page on your right which I've taken from an anti-smoking booklet aimed at Aboriginal people.

Questions

- Why do you think this page works for Aboriginal people? Name three elements that Aboriginal people can relate to.

- Search other media (newspapers, magazines, the web) and find similar advertisements made to appeal to Aboriginal people.

- Pick another nationality and imagine how you would design an ad just for these people.

If you quit smoking today…

Smoking subjects the body to severe changes which take a long time to neutralise. If you stopped smoking today [27][28],

- blood circulation to hands and feet would improve,

- in 8 hours excess carbon monoxide is out of your blood,

- in 5 days most nicotine has left your body,

- in 1 week your sense of taste and smell improves,

- in 2 months your blood pressure would return to normal,

- in 3 months your lung function increases by 30% and regains the ability to clean itself,

- in 9 months your risk of pregnancy complications is that of a non-smoker,

- in 1 year your risk of dying from coronary heart disease halves and you saved between $5,000 and $4,000,

- in 5 years your risk of mouth or throat cancer has halved, and your risk of a stroke decreased dramatically, and

- after 15 years your risk of coronary heart disease and stroke would be almost back to that of a non-smoker.

Story: "I thought I'd never pull this off"—A quitter's story

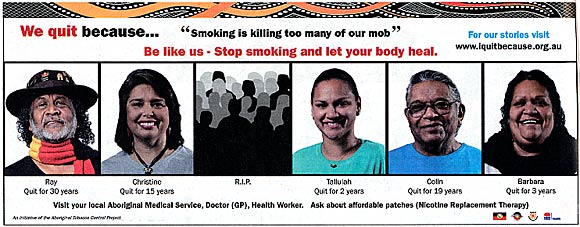

Positive role models within Aboriginal communities can significantly contribute towards Aboriginal people quit smoking. Carol Martin, Aboriginal woman, West Australian Labor MP and a smoker for 39 years, quit smoking in 2009.

"I have to say I thought I'd never pull this off because the only time I didn't smoke was when I was pregnant and had little breast-feeding babies, but once they were off the boob I was back on the fags," reveals Carol [18].

"I had a bit of a sore throat when I gave up and I remember getting desperate to go and get a smoke but I resisted and I'm glad I did."

"I've got diabetes and hypertension, so my smoking was actually masking my illnesses. So giving up made me realise I had to get a handle on my health," Carol says.

The best part about giving up smoking, according to Carol, was the money she has saved in the half year following her abstinence.

"I've saved more than A$2,000 since I gave up because I would keep giving them out to my mates. But since I gave up, I notice I haven't got so many mates around anymore, but that's just a laugh."

"So giving up will allow me, as a mother and grandmother, to take my place in the community and have a major impact on their future and push them to be the best that they can. I enjoyed smoking, but I enjoy not smoking even more."

Giving up [smoking] will allow me, as a mother and grandmother, to take my place in the community and have a major impact on their future.

— Carol Martin, West Australian Labor MP [18]

To raise Aboriginal people's life expectancy it is very important to get them to give up smoking.

Getting help quitting

Children can be the best ambassadors to help families quit smoking. A survey found that families had gone completely smoke-free because of the influence of their children spreading the word. [12]

Programmes that support Aboriginal people quit smoking can be more successful if they consider the following: [2][26]

- Employ Aboriginal people. By employing Aboriginal educators and health workers Aboriginal smokers more likely receive the message to quit.

- Easy language. Talk to smokers in a simplified manner that they can understand easily.

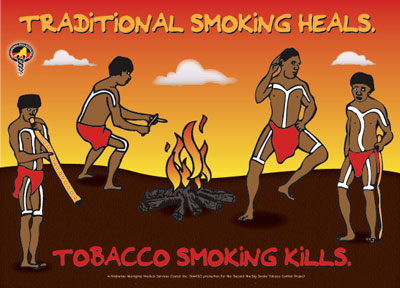

- Use cultural elements. By using cultural and traditional elements you convey a better picture of why Aboriginal people need to stop smoking. Health promotion messages also need to address the challenges Aboriginal smokers face when quitting.

- Replacements. Offering subsidised access to oral forms of nicotine replacement therapy can help particularly mothers if they cannot quit during pregnancy.

- Better training. Train clinicians to offer quit advice, even when the outcome is unknown, and prescribe replacement therapies.

SmokeCheck

SmokeCheck is a program designed specifically for Aboriginal people. Health workers use culturally specific resources to support clients quitting and offers future check-ups.

For more information visit SmokeCheck.

Aboriginal Tobacco Control Project

The project aims to reduce smoking in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and provides information for smokers wanting to quit, and inspirational stories from those who have.

Read more information about the project or its final report.

NoSmokes.com.au

NoSmokes.com.au is a multimedia anti-smoking project that uses humour, music, games (interactive biopsy anyone?) and highly visual mediums to appeal to young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders.

NoSmokes.com.au is a project of the Menzies School of Health Research and funded by the Department of Ageing.

"Have you thought about quitting the smokes?"

The WA Department of Health has put together a concise guide to quitting smoking, along with Aboriginal-themed illustrations.

Tackling Indigenous smoking program

This is a national program providing funding for regional activities that will reduce the number of people taking up smoking and encourage and support people to quit. It is run by Dr Tom Calma, an Aboriginal elder from the Kungarakan tribal group.

Blow Away the Smokes

Blow Away the Smokes is a 30-minute film addressing Aboriginal people and offering practical help for quitting. It features local scenes and Aboriginal community members.

"Blow Away the Smokes Day" has been created in 2012 and is celebrated on March 12 each year.

Watch the Blow Away the Smokes video.