Land

Aboriginal homelands & outstations

Homelands are proven to make Aboriginal people healthier and stronger, but they are expensive to live in and don't get much love from the government.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

Selected statistics

Origin of the homelands movement

The homelands movement began in the early 1970s in the Northern Territory. Small Aboriginal groups – often families or other closely related people – left mission-run larger communities and moved back to their traditional and often remote land. They did this for a number of reasons.

- Escaping dysfunction. Aboriginal people were leaving major settlements because there was a high level of social dysfunction and political instability. Rising levels of petrol sniffing, marijuana, youth suicide, teenage pregnancy and disrespect for elders made them want to get away from bad influences. When the government closes communities (as it happened in WA), residents move into larger communities, adding to the social pressure.

- Duty to uphold birth country. Aboriginal people have a strong connection to their land which includes a duty to look after it and, for example, maintain renewal cycles or protect sacred sites.

- Maintain customs. It is much easier to maintain customary ways of living on country than away from your homeland.

- Land rights movement. The land rights movement started in the mid-1960s and saw Aboriginal people claiming ancestral lands for the first time.

- Reject government policies. With their move to homelands, thousands of Aboriginal people rejected policies of centralisation and assimilation at government settlements and mission stations, especially as government policies shifted to self-determination in 1972. [2]

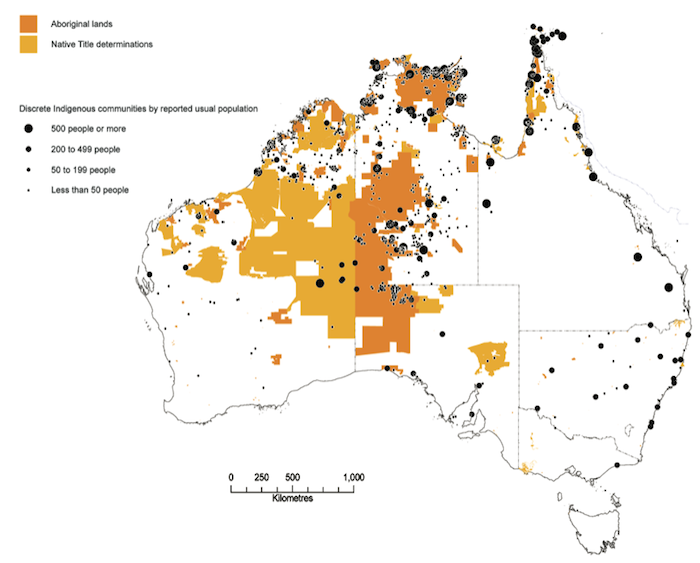

Allan Blanchard MP, who authored the 1987 Return to Country: The Aboriginal Homelands Movement in Australiareport, defined homelands as "small decentralised communities of close kin established by the movement of Aboriginal people to land of social, cultural and economic significance to them”. [2] In some regions homelands are called outstations. They are generally tiny villages with small, fluctuating but committed populations of fewer than 50 people. [2] Fluctuations occur because only some people live there permanently. Others join depending on season or occasion.

"Homelands give Aboriginal people a sense of 'home' and a sense of belonging while contributing to their cultural responsibilities of caring for their country and managing the natural resources of their land and seas," explains Kim Hill, CEO of the Northern Land Council. [4]

Extended families in the larger towns also frequently visit their homelands to spend restorative time there, reconnecting with their culture and traditional country.

In 20016 the Australian Bureau of Statistics counted 547 homelands in the Northern Territory with 10,342 people, with an average of 19 people per community. In 2016 there were 630 homelands with an estimated minimum population of 4,532 and a maximum of 11,174. 70% of homelands were occupied 70% of the time. [2]

Homeland communities hold the language, the culture.

— Lionel Fogarty, Aboriginal poet [5]

Yothu Yindi's first album is titled "Homeland Movement".

Homelands contribute to health

Northern Land Council CEO Kim Hill says that "it is also well-documented that homelands contribute significantly to Aboriginal people's overall health, well-being, and importantly, to their thriving art practice and industry which provides an economic base when none other exists." [4]

Studies by the Menzies School of Health in Arnhem Land and at Utopia confirm this view [7] and indicate that Aboriginal people living on homelands are also less likely to be involved in substance abuse, poor eating habits and violent behaviours because they maintain their traditional lifestyle away from the influence of the big towns.

The healthiest way to live is on land, on community, on country, eating bush tucker and not the crap from town.

— Warwick Thornton, Aboriginal director [8]

Spiritual lands

Aboriginal homelands are places where the ceremonial grounds are and "strong discipline comes through the spirits of our fathers talking through the land," says Yingiya Guyula, a Yolngu studies lecturer at the University of Darwin. [9]

Spirits are the reason those living on their homelands cannot be moved on other people's land. "The spirits don't recognise us," says Yolngu man Dr Gawirrin Gumana. [10]

Also, outside the homelands traditional lawmen have no authority and Aboriginal people would be exposed to and learn the white man's way with all its threats to Aboriginal culture. [10]

Government wants growth hubs

This flies into the face of the NT government which prefers Aboriginal people to move into "growth hubs" where it could centralise health and education services. It makes this clear by allocating to homelands only a tiny fraction of the budget it allows for growth towns with regards to housing. In the financial year 2010/11, homelands, where approximately 35% of the NT's Aboriginal population live in 500 communities, received only $7 million, while growth towns, with 24% of the population in 21 communities, received $672 million. [11]

Rosalie Kunoth-Monks, Alywarr and Amnatyerr elder from the Utopia homelands, comments on that policy: [12]

"Let me assure anybody who cares for the Aboriginal people of Australia that once we are moved from our place of origin, we will not only lose our identity, we will die a traumatised, tragic end.

"We cannot have identity if we are put into these reservations that are now called growth towns, we will become third-class, non-existent human beings."

No English words are good enough to give a sense of the links between an Aboriginal group and its homeland… our word 'land' is too spare and meagre.

— Professor W.E.H. (Bill) Stanner in his 1968 Boyer Lecture, 'After the dreaming' [13]

Video: "I am my homelands"

Watch Rosalie Kunoth-Monks from the Alyawarr and Anmatyerr Peoples explain 'homelands': "It holds your language, it holds your customary practice..."

A safe haven: Benefits of living on country

Living on homelands has many benefits: [14]

- Escape from alcohol. Ahead of fortnightly 'barge weekends' when alcohol travels into the communities many young women and their grandparents flee the bigger centres and travel to their homelands to escape alcohol-related problems. Prior to the Northern Territory Intervention in 2007, Aboriginal community elders were responsible for 80% of homelands being dry communities. [15]

- Less stress. When Aboriginal people move to homelands they "come back to the peace and quiet", [16] an environment better suited for their children too. Youth suicide, teenage pregnancies and other signs of community breakdown are far less likely on homelands.

- Art and inspiration. Aboriginal artists appreciate the tranquillity and spiritual connection they get being on their homelands. They gain an income from selling their art. The homelands movement of the Western Desert peoples nurtured an explosion of creativity on canvas. [17]

I cannot paint when I'm not on my land. My art exists because of my connection to my homelands.

— Kathleen Ngal, Aboriginal artist from Utopia [1]

- Keeping culture alive. Living on their homeland Aboriginal people keep alive their cultural practices and knowledge. It gives them a purpose and encourages them to pass on their skills to the next generation. There is no 'contamination' of culture. "I am a leader on the homelands - we always want to describe from our homelands. We want to tell this is where the songs are coming from. This is where the patterns are coming from. This is where the kinships are," explains Yolngu elder Djambawa Marawili. [18]

- Strong relationships. By doing things together family members strengthen their relationships.

- Caring for country has, apart from physical effects, important psychological and social benefits. Aboriginal people monitor and care for very fragile and pristine landscapes. They work for environmental protection, bio-security, fire management and, sometimes, border protection.

- Escape from beggars. In larger communities it is common that relatives and friends of Aboriginal people beg for money or goods ('humbugging'). Moving to a homeland allows them to escape: "I felt I really wanted to get away from humbugging, people getting, digging my mind, my brain... I want to be really living on the homeland because I like homeland. This is a place where I don’t get into a lot of situations and I can do what I like, and this is what I feel." [18]

- Economic opportunities. Homelands offer income opportunities through jobs for conservation, environmental services, carbon farming, culling of feral animals and cultural industry. [2]

- Healthier country, healthier food. On homelands Aboriginal people hunt introduced species like buffalo and pig. They improve the country and manage the land. They also harvest bush medicine. Less stress and more exercise means better health. A 10-year study in the NT has shown that death rates on homelands were 40 to 50% lower than the territory's average for Aboriginal adults. [10] Paradoxically, moving Aboriginal people away from homelands in an attempt to deliver better health and other services severs the link to country that gives them both physical and psychological health. [19] Researchers found that for a small community of just over 1,200 people about $260,000 in treatment costs can be saved per year if there was greater involvement in 'caring for country'. [20]

- A place for self-determination. Homelands enable residents to take matters into their own hands, for example setting up community-managed stores, schools or business enterprises (for example weaving). They are also more self-sufficient, more active and productive and less dependent on income support. [2]

- Better education. There is evidence that education on homelands and country boosts attendance. [2]

- Escape from virus pandemics. During the corona virus (COVID-19) pandemic in 2020 a lot of Aboriginal people fled to their homelands because they were afraid of catching the virus. Many Aboriginal people suffer from several health problems (especially the elderly) which makes them more vulnerable to diseases.

Homelands are like banks. Not for money but for security, knowledge and culture.

— Jimmy Pascoe, traditional owner, Maningrida, West Arnhem Land, Northern Territory [14]

Case study: Safety and self-determination at Mapuru

This is what Aboriginal people from Mapuru said about their community which is 500 kilometres east of Darwin.

"Our fathers and grandfathers established this community – so we could be happy on our own land. So we could be happy, we could feel at home. We feel safe here.

And it is really for the children. We want our children to have a school where they learn their culture and language, and Yolngu [Aboriginal] and Balanda [western] ways together. This is a good place, good and quiet—good for our kids.

We don't want them going to Galiwin’ku [30 kms north-east of Mapuru] or other big places [where there are bad influences]. We want them in this safe place – at school in this place. We don't want to be pushed around by government. We want to be safe in our own home, away from places where there's lots of trouble." [22]

Arnhem Weavers successful without external money

The Mapuru homeland community runs a cultural tourism project, Arnhem Weavers, where they have cultural tours and workshops for small groups of tourists who can come and live in Mapuru for 1-2 weeks, and learn about weaving and other traditional activities.

For 7 years the project has grown without any government funding or external assistance. This is a source of pride for the community members. [16]

Award-winning community co-op

In 2002 the community launched a food cooperative replacing unhealthy, highly processed food with food they actively hunted and collected.

People can only buy if they can pay. All profits go into local community projects.

In 2004 the shop won a National Heart Foundation award for a Small Community Initiative because it ensures that there are nutritious foods available all year round. [23]

Making the shop part of the school helped increase numeracy and literacy and improved students' diet. Shop employees' self-esteem and English language skills increased.

Food on homelands is expensive

The advantage of remoteness from big cities is also one of the biggest problems of homelands. A shopping basket of groceries worth A$240 in Cairns can cost as much as A$370 on Thursday Island and other remote communities, [24] while income is generally lower.

The cost of fuel, freight and refrigeration all add up, and by the time food reaches a remote community it is far more expensive and far less fresh than it would be in urban regions.

Some stores run by a government-owned organisation set prices up to 400% higher than those in metropolitan and even rural areas. [25]

No surprise that Aboriginal people in homelands turn to cheaper, poor-quality foods like soft drinks, sweets and deep fried products which last longer.

Many communities have just one shop, others no shop at all, and for some communities food needs to be flown in during the wet season when all access roads are closed. The lack of competition is another factor driving up prices.

In coastal areas fresh food is often delivered by weekly barges. On 'barge day', half a cauliflower can go for A$12 in remote areas. [24] Aged pensioners unable to make it to the shop as food is being unloaded miss out on the best and freshest produce.

During the tourist season, visitors buy most supplies. [26]

Consequently people in these communities have one week of healthy supplies and eat high salt and high sugar foods the next, contributing to their poor health condition.

Sara Hudson, an analyst with the Centre for Independent Studies, suggests that Aboriginal people in homelands grow their own fresh fruit and vegetables to be independent of road closures and encourage individual responsibility for a healthy diet. [27]

I refuse to pay $32 for six frozen chop sticks.

— Ali Cobby Eckermann, Aboriginal poet [5]

| All prices in Australian Dollars [28] | Melbourne, VIC (Woolworths) | Katherine, NT (Woolworths) | Beswick / Wugularr remote community (Licensed store) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Powdered milk | 6.44 | 9.50 | 14.95 |

| Loaf of multigrain bread | 1.79 | 2.28 | 3.00 |

| Weetbix cereal 1kg | 4.60 | 5.04 | 7.21 |

| Frozen vegetables 1kg | 1.71 | 3.99 | 7.01 |

| Vaalia double pack yoghurt | 3.20 | 2.55 | 3.54 |

| Tinned tuna, 425g | 2.35 | 3.65 | 6.90 |

| 12 eggs | 3.30 | 3.99 | 5.69 |

| Packet of Vita Wheat biscuits | 3.00 | 3.05 | 5.60 |

| 1kg lean beef (diced rump) | 14.92 | 5.63 | 10.84 |

| Bottled water 1.5l | 0.77 | 1.32 | 4.04 |

| Total | 42.08 | 41.00 | 68.78 |

Price for six apples at the Aboriginal community on Palm Island: $25. Unemployment rate: 97%. [29]

Homelands are expensive to support

Homelands are expensive to support, there is no doubt about it. Remoteness, low population and expensive transport are just some factors that push costs up. On top of that some communities suffer from domestic violence, sexual abuse, drug and alcohol-related harm. Governments spend millions supporting homelands – and don’t like it at all.

Since the 1967 referendum gave the Commonwealth the power to make laws for Aboriginal people, the federal government has funded the delivery of essential services to remote Aboriginal communities. [30] They had to – without private property ownership Aboriginal people could not pay rates to fund local governments.

When the Northern Territory gained self-government in 1978, the Commonwealth remained in control of homelands, a move that annoyed the NT government. Consequently, it did as little as possible for the thousands living on homelands. [2]

The federal government ran two programs crucial to homeland living:

- Community Development Employment Projects (CDEP), a scheme that provided flexible basic income support, and

- Community Housing and Infrastructure Program (CHIP) which delivered basic infrastructure and some housing, and funded community agencies that provided support and development assistance. [2]

Shortly after the Northern Territory Intervention the federal government handed responsibility for homelands back to the NT.

In 2014 the federal government tried to pass funding to state governments, prompting these to threaten to close communities which were “not viable”. Western Australian Premier Colin Barnett said at the time that “communities were not just unviable in a financial sense but because of social dysfunction, child abuse and neglect, poor education and a lack of opportunities.” [30]

Senior ceremonial leader and leader of the Yolngu Madarrpa clan, Djambawa Marawili, of North East Arnhem Land, challenges the government to learn more about homelands to support communities help themselves.

"If you in government want to see what is happening then give us someone who can support us. You are missing a lot of information about our homelands. You can only see that nothing is happening in homelands but if you only spent your money wisely and to support and strengthen homelands, I reckon that is one of the really important things that you are leaving [a] foundation for the next government change." [18]

Closing homelands has severe consequences

For governments it is easier to close and bulldoze Aboriginal communities than support them even if they are struggling.

But no-one would ever contemplate closing down Savage River in north-western Tasmania, a small mining community of 158 people which lost more than 85% of its population between 1986 and 1996. [31]

Closing homelands has severe consequences:

- Problems are transferred, not solved. Relocating people from homelands to small towns without adequate support services transfers some problems from one place to another and creates new ones.

- People become homeless. While some former homeland can move in with family (exacerbating overcrowding), others might need to camp ‘in the long grass’, ie. sleeping rough on the fringe of towns. Three years after the closure of Oombulgurri some were still homeless. [30]

- Loss of government benefits. Because displaced people cannot receive correspondence they lose their entitlement to government support such as unemployment benefits.

- Children don’t go to school. Due to a shortage of appropriate housing many former homeland children cannot attend school regularly, driving Aboriginal school attendance rates further down.

- Alcohol abuse. People removed from their homelands drink more in towns due to the ready access to alcohol, attracting police attention in the process.

- Trauma. Tammy Solonec, Indigenous Peoples' Rights Manager at Amnesty International Australia, explains: "When you push Aboriginal people off their homelands, it's going to create trauma… and the trauma that it creates is not trauma that can be overcome easily. It's trauma that becomes intergenerational, that you're then going to have to deal with through social consequences for years later." [30]

The testimonies we gathered universally tell not of voluntary departure but of forced eviction.

— Tammy Solonec, Indigenous Peoples' Rights Manager at Amnesty International Australia, about the closure of Oombulgurri in Western Australia [30]

State or territory governments forcibly closed and destroyed the Aboriginal communities of Mapoon (QLD, 1963) [32] and Oombulgurri (WA, 2014). [30]

Homeland schools neglected

- $16,500

- Total money spent by the government over 10 years when the school in Gawa, Arnhem Land, was a government-funded Homeland Learning Centre. [33]

- $538,000

- Total money granted by the government over 6 years since the school in Gawa became a non-government, private school. [33]

From the figures above you can see that the Australian government has no interest in funding government-run schools. When the school in Gawa was a Homeland Learning Centre, they were given discarded desks and chairs from the NT Department of Education.

After a decade the school still had no toilet, running water, or power supply, there was no fax machine, computer, photocopier or any of the other equipment usually found in a school while computers, satellite connections, printers and access to distance learning were provided to every remote school and 66 cattle stations in the NT. [33]

A cattle station might have as many as one pupil, while some homeland schools have more than 40. (Read the full story: Build a Future for Our Children)

The Aboriginal Land Rights Act (Northern Territory) ensures that anything that is built on lands trust land, including homelands, becomes owned by the traditional owners. [14] Hence governments have few incentives to spend money on homelands and instead inject it into bigger centres where it can own what it builds.

Policies which fail to support the ongoing development of homelands will lead to social and economic problems in rural townships that could further entrench Indigenous disadvantage and poverty.

— Tom Calma, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner in 2010 [34]

Video: Elders pledge for homeland support

In 2009 a delegation of elders from across East Arnhem Land visited Canberra and pleaded with politicians to help them to rescue future generations by allowing them to live on their homelands. The elders presented a petition of over 27,000 signatures urging the government to secure the future of homeland communities.

Problems with homelands

Apart from benefits homelands also have disadvantages.

- Minimal infrastructure. Communities on homelands are usually small and infrastructure is minimal. Many rely on generators for power and have only one single public phone to communicate with the outside world. Satellite services can fail during the wet season [35] meaning that emergency information is unavailable, and in 2019 the largest homeland in Kakadu (NT) had no running water after the water bore they relied on stopped working. [36]

- Mental effort. It might take a lot of strength of character, discipline, self-reliance and responsibility of individuals to live in a small, remote community. [37]

- Broken homes. Governments provide little public housing, and if they do homes can be run down. Repairs take longer because of distance. A third of Aboriginal adults in remote and very remote areas are living in homes where toilets and taps may be broken. [36]

- No internet. Also, it is very unusual for people living in outstations to have access to a computer and the Internet. In a small group of interviewed people, only 6% had a computer at home [38], while the interest for access was high. The main barrier to more computer access is money.

- Inaccessibility. During the wet season homelands can be inaccessible by land for extended periods of time. Flights are the only, albeit expensive, alternative.

- Temporary places. The vast majority of people don't live permanently in homelands, because they have limited access to what they own and little knowledge of funding and how to get it. For them, homelands are places of respite or cultural ceremony only. [39]

- Pollution. Tests detected unsafe levels of E. Coli, Naegleria (amoeba commonly found in warm freshwater) and uranium in as many as 68 communities [40] both of which cause serious illness and can be fatal.

- No dedicated government policy. Both the Commonwealth and Northern Territory governments have so far failed to develop sustainable policies for homelands because government policies are usually crafted for stable places and populations. [2]

- Trauma is buried, not healed. Despite all efforts to escape family violence and substance abuse, "the long reach of trauma and abuse lie[s] close to the surface of daily life" in Aboriginal communities, [37] even homelands.

- Hiding place for perpetrators. Western Australia's former Minister for Child Protection, Helen Morton, claims that "the most dangerous" perpetrators of abuse and violence use remoteness as a tool to shield them from prosecution. [37]

Homework: What is 'remote'?

Media routinely use the word 'remote' to describe Aboriginal communities and homelands. We understand these to be remote from where we are.

Brenda Croft, a Gurindji/Malngin/Mudpurra artist, challenges that notion: "They say this is about ‘remote’ communities — but these communities are living on their ancestral land. It is we in the cities who are remote from them." [41]

Questions

- How would you define 'remote' for yourself?

- Compare Brenda's definition with your own. What is different? What is similar?

- What are the implications of "we in the cities" being remote from Aboriginal homelands? Discuss for both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people.

Resources

Read more about Aboriginal homelands on the Amnesty International website.