Land

The 1963 Yirrkala bark petitions

In 1963 the Australian government took 300 square kilometres of land from the Yolngu people in Arnhem Land without even asking them. Wanting their voices to be heard, the Yolngu people submitted two bark petitions that made history, but didn't help them.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

Who created the petitions, and why?

On 13 March 1963 the Australian government took more than 300 square kilometres of land from the Yolngu people in Arnhem Land so mining company Gominco could extract bauxite. As so often, work started without talking to the people about their land.

In July 1963, Yolngu leaders made plain to government representatives their objection to the lack of consultation and secrecy of the government's agreement with Gominco, and their concern about the impact of mining on the land unless their voices were heard.

Wali Wunnunmurra, 17 at the time, and one of the few signatories still alive at the petition's 50th anniversary, remembers: "Minerals to Aboriginal people at that time was a foreign idea. The old people saw them as pinching our land while they were digging for minerals, taking away land from us - something very, very serious in Aboriginal culture." [1]

This [is] aboriginal people’s place. We want to hold this country. We do not want to lose this country.

— Milirrpum, signatory on the Bark Petition [2]

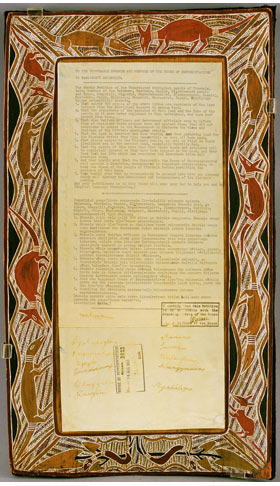

Requesting an inquiry and asserting their ownership of land, the Yolngu created petitions using painted designs to proclaim Yolngu law, depicting the traditional relations to land. Inside the painted frame they added typed text in English and Gumatj languages.

These petitions are the first to use traditional forms and combine bark painting with text typed on paper.

The Yolngu people sent the petitions to the Commonwealth Parliament in August 1963.

The signatories of the Yirrkala petitions were quite young: Their ages ranged from 18 to 36. [3]

Why were there two petitions?

The Minister for Territories, Paul Hasluck, challenged the validity of the signatures of the first petition, signed by 12 clan leaders from the Yolngu region, [1] a move that was widely understood as rejecting the petition. [3]

When they learned of Hasluck's rejection, the people of Yirrkala decided to send a second bark petition, this time accompanied by the thumbprints of clan elders, so there could be no doubt that they approved of the petition.

The English text of both petitions is identical.

How did the government respond?

Politicians presented the two petitions to the House of Representatives on 14 and 28 August 1963.

A parliamentary committee of inquiry listened to evidence presented at Yirrkala and in Darwin. The committee's report acknowledged the rights the Yolngu set out in the petitions and recommended to Parliament on 29 October 1963 that compensation for loss of livelihood be paid, that sacred sites be protected and that an ongoing parliamentary committee monitor the mining project. [4]

But the Yolngu people failed in their attempt to get justice. Mining did go ahead near Yirrkala, and by 1968 a massive bauxite refinery was built at Gove, 20km to the north.

When their appeals to Parliament failed, the Yolngu leaders turned to the Supreme Court in the Northern Territory, where hearings in their case, known as the Gove Land Rights Case, began in 1968.

This case also failed.

Handing down his decision in 1971, the judge accepted the evidence that Yolngu had been living at Yirrkala for tens of thousands of years and that their law was based on intricate relations to land.

He held, however, that Australian law could not recognise these as property relations and that this law as it stood could not solve the problem at the heart of the case: that the facts of Australian history disproved the 'legal fiction' of terra nullius, on which Australian law was built. [4]

Why are the Yirrkala petitions still relevant today?

One result of the bark petitions was wider awareness of the just claim of the Yolngu, and of the problems of Aboriginal people throughout Australia.

The inability of the law to find a just answer to the Yolngu, who had been turned away first by the Parliament and then by the courts, inspired a national protest. [4]

But the petitions also set off a debate that led to the Land Rights Act in 1976 and, in 1992, to the High Court's Mabo decision overturning the 'terra nullius' concept and recognising Aboriginal occupation of Australia before European settlement.

It also paved the way for the 1967 referendum in which Aboriginal people were recognised as Australian citizens for the first time.

The petitions became the first traditional native title documents recognised by the Australian parliament.

During NAIDOC Week in 2013 Australia celebrated the 50th anniversary of the petitions. Prime Minister Kevin Rudd compared them with the 1215 Magna Carta, one of the founding documents of the British legal system.

"These bark petitions are Magna Carta for the indigenous peoples of this land," Prime Minister Kevin Rudd said. "Both (are) an assertion of rights against the crown and both therefore profound symbols of justice for all peoples everywhere." [5]

When Nabalco wanted to call its new town "Gove", Yolngu insisted it be called Nhulunbuy, their name for the nearby sacred hill. Again, Yolngu sent a bark petition to Canberra and on this occasion parliament granted their request. This petition sits on display in Parliament House between the two petitions from 1963. [3]

Homework: Compare the Yirrkala bark petitions to the NT intervention

Find out the exact text of the Yirrkala bark petition. [3] Then read the article about the Northern Territory intervention.

- Which analogies can you find in both events?

- Imagine you lived in the NT at the time of the intervention. How would you word a petition to parliament? Who should write it?

- What has changed for Aboriginal people since 1963? What hasn't?