Arts

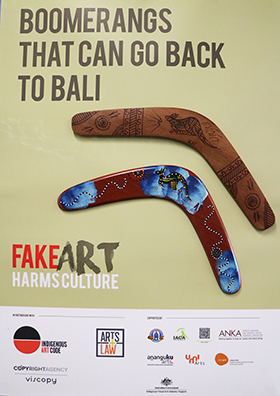

Fake or real? Aboriginal art authenticity

If you buy a piece of First Nations art from the shops there's a high chance it's fake. What can you do?

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

Selected statistics

Most 'Aboriginal-style' art is fake

Aboriginal art and craft is a core element of cultural identity. It encodes stories and history of peoples and communities and is about connection to Country, identity and belonging. Reflecting First Nations diversity, different communities have different stories and artistic styles, which only that community is allowed to produce.

It is wrong to think of Aboriginal art as a collection of design elements that are free to use. When non-Aboriginal people copy an artwork without permission or attribution, it can profoundly harm artists and denigrate the meaning of their imagery and its cultural significance. It is also a misappropriation of culture.

| Product | Creator is not First Nations | Creator is First Nations |

|---|---|---|

| Boomerang | 60 | 33 |

| Didgeridoo | 60 | 40 |

| Bag | 93 | 7 |

| Keyring | 97 | 3 |

| Magnet | 91 | 9 |

| Coaster | 92 | 8 |

| General souvenirs | 83 | 11 |

| All | 70 | 23 |

Numbers are rounded and exclude ambiguous status. [3]

Despite this, fake Aboriginal art is omnipresent. You might come across tags like 'Aboriginal-style' which often labels fake art mass-produced by non-Aboriginal people, usually without the consent of the original artist. Many sources estimate that at least 80% of these products are not produced by Aboriginal artists. [5][4][6][7]

Many regard this as stealing both their culture and potential economic success. Exact figures are unknown, but an analysis by Tourism Research Australia for 2017–18 found that about 20% of international visitors in that year purchased Aboriginal art, crafts or souvenirs [7] – a potential for hundreds, if not thousands, of millions of dollars.

Fake art is made in India, Indonesia and China.

Gabrielle Sullivan, chief executive of Indigenous Art Code, investigated art shops over a period of 6 months. "Of the shops — or galleries if you can call them — that we went to as part of this research I would say that 80 per cent of those shops were selling things that were not authentic," she found, [4] a figure the Aboriginal Art Centre Hub of Western Australia agrees with. [6]

There have been attempts to introduce labels to authenticate Aboriginal art to enable buyers to distinguish between what has been produced by First Nations peoples and what has not, but they were not successful. A more recent attempt added a chemical fingerprint to the painting, but this is not practical for the average buyer.

I’ve got a boomerang in front of me… It sells for $4 retail in the shop. It’s been hand painted. You can’t even make a boomerang for $4. Did an Aboriginal artist or person make that, paint it and then package it and sell it to the shop? It’s just not possible. [7]

Can you replicate an Aboriginal painting style with your own work?

Many people keen to immerse themselves into Aboriginal culture are also playing with the idea of creating a painting using an Aboriginal art style. Is that ok to do?

No. Although you might have no bad intentions, replicating a painting is not only unethical, it might also seriously offend First Nations people if, for example, the sample painting you have used for inspiration holds sacred knowledge that is not intended to be painted by the opposite sex.

London-based artist Timna Woollard experienced this first-hand. A painting she made copied elements that Aboriginal artists considered to be men's business. Woollard's painting was also used in a British comedy series broadcast on Netflix where it featured prominently in the lead character's living room, [8] a move First Nations people considered 'stealing'.

Don't replicate Aboriginal art. Buy originals and support First Nations artists instead.

The material they call Aboriginal art is almost exclusively the work of fakers, forgers and fraudsters.

— Marion Scrymgour, former NT Arts Minister [9]

Unfortunately a great many [of wholesalers] are either unaware of or uninterested in the issue of authenticity.

— Standing Committee on Indigenous Affairs [7]

It is not illegal to sell fake Aboriginal-style souvenirs under Australian Competition and Consumer (ACCC) laws. [4] Both the Australian Consumer Law and copyright law are inadequate to protect First Nations cultural expressions. [7]

Most non-Aboriginal Australians and foreign tourists cannot tell whether an Aboriginal art and craft item is authentic or not. [7]

Is this item authentic Aboriginal art?

Commonly there are four elements used to identify an artwork as “authentic” Aboriginal*:

- A story. A story, most often related to the Dreaming, should be associated with the artwork. Problem: Not all pieces need a story, e.g. body markings or depictions of country. Some paintings come without a story, deliberately or by accident.

- The artist is Aboriginal. Problem: There can be a fine line between an Aboriginal artist’s contribution to an artwork. For example, is a didgeridoo that is mass-produced by non-Aboriginal people, but painted by First Nations people, an authentic Aboriginal product? There are even greater problems with artwork produced by First Nations people of mixed descent who often find themselves having to defend their identity.

- Authority to use style or symbols. Has the artist the authority from the relevant members of the Aboriginal community to paint in a particular style or using a particular set of motifs or icons? Problem: How can you assert this? Even gallery staff can have difficulties answering this question. As a minimum, galleries should provide documentation about the origin of the artwork, for more expensive items also about its sales history.

- Cultural relevance. Does this art come from, and is within the bounds of, traditional First Nations culture? It wouldn't be authentic if a mainland Aboriginal artist used the Torres Strait Islander style. Problem: This can be hard to establish.

What can you do?

As a layperson it is extremely hard to establish the authenticity of an Aboriginal work of art. Stores often sell fake and authentic products side-by-side. Authentic Aboriginal art should credit the ancestral lands the object was produced from or which language group they represent.

In the absence of a national label of authenticity your best bet is to buy from a gallery, art centre or at an art fair. Make sure you visit an First Nations-owned and controlled business before you decide to buy, or try Aboriginal festivals and art fairs, including local markets.

Avoid gift and souvenir shops, large markets, and businesses in high volume tourist locations. Research First Nations-owned businesses ahead of your travel so you know where to go. Know which materials First Nations artists do not use for their works, e.g. bamboo.

Note: Consult an expert when in doubt about a piece of Aboriginal art. Businesses have been taken to court over art classified as 'Aboriginal' when it was not. Be especially mindful before buying from online auction sites. See ACCC v Australian Dreamtime Creations for a sample case.

How can you ethically buy a boomerang?

Show

Whilst almost everyone has heard of a boomerang and could sketch one, very few can describe its historical and cultural significance to First Nations peoples or describe the different types that exist.

To ethically buy a boomerang, learn about its history, types and significance. This will also help you make a better buying decision.

There are often also subtle 'marks of authenticity' embedded in First Nations paintings. Many desert art artists paint out in the open where it's dusty. The works of Emily Kame Kngwarreye, from the Utopia community in the Northern Territory, are known to contain hairs of her brushes or little bits of sand from the places where she was painting.

When we painted, people walked over [the paintings], dogs slept on them when we stopped.

— Kumpaya Girgirba, Martu elder and artist [10]

Stories about fake Aboriginal art

Be careful when you buy items marked as 'Authentic Aboriginal Art'. They might not be.

In April 2010 Mayvic Pty Ltd, an Australian household goods wholesaler, had to withdraw fridge magnets featuring Aboriginal rock art after the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) raised concerns about its authenticity [11].

The company acknowledged that its conduct was likely to have breached the Trade Practices Act 1974.

In October 2018, the Federal Court of Australia found that Queensland-based souvenir wholesaler Birubi Art had misled consumers over its fake Aboriginal art.

For almost 2.5 years, Birubi sold over 18,000 boomerangs, bullroarers, didgeridoos and message stones to retail outlets around Australia which were made in Indonesia, while the artwork, images and statements used by Birubi suggested that First Nations people were involved in the production.

"The ACCC is particularly concerned about any conduct that has the potential to undermine the integrity and value of genuine Indigenous Australian art, and consequently, the impact that could have on Indigenous Australian artists," the ACCC said. [12]

Birubi Art was fined $2.3 million for breaching consumer law with its fake Aboriginal art.

Any product, from expensive fine art works to small souvenir items such as fridge magnets, must come with accurate authenticity claims.

Many First Nations artists rely on pro bono legal support to take action when they identify problematic uses of their culture. [2]

Story: "I started pulling everything off the bloody rack"

In 1991, the clothing manufacturer Dolina Fashion Group Pty Ltd supplied Grace Bros stores with an 'exclusive' dress design for a major promotion through its network. It was alleged that Dolina's stylists had requested an Aboriginal look from the Japanese fabric maker Sastani to present as the front line of their fashion range.

The problem was that the print supplied by the fabric maker was a direct copy of an original work by First Nations artist Bronwyn Bancroft, Eternal Eclipse (1998), which had been reproduced illegally. Here's how Bronwyn recalls the case [13].

"It's a funny thing when you're sitting down with a bunch of other Aboriginal people and you're having a cup of tea and someone hears the mailman and goes out and gets the little brochure and brings it in. There's a couple of letters and then there's the Grace Brothers/Myers catalogue. And so I flicked through that.

And then all of a sudden I see this really revolting outfit with my painting. Eternal Eclipse, on it!

So I raced over to Broadway [shopping centre]… So we actually went over to Grace Brothers and I started pulling everything off the bloody rack. The manager descended and said 'What are you doing?' and I went, 'This is my work, how dare you?'… And I said, 'I demand to see your Manager. I want to know who supplied this. I demand they be taken out of this shop immediately.'"

Bronwyn's case was settled out of court and – among others – motivated the development of the National Indigenous Arts Advocacy Association's (NIAAA) Label of Authenticity.

It was only Aboriginal art. I didn't think I had to ask anybody.

— Justification for the copyright infringement, according to Bronwyn Bancroft [13]

One of the 'brightest stars' in Aboriginal art, Sakshi Anmatyerre, whose buyers included the Sultan of Brunei, the Brisbane Broncos, Paul Hogan and the family of media tycoon Kerry Packer, turned out to be an Indian artist named Farley French [14].

Attempts to establish a label of authentication

In late 1999 the National Indigenous Arts Advocacy Association (NIAAA) tried to introduce an authentication label aimed at promoting genuine products and deterring fraud in the Indigenous arts and crafts industry. The idea was to finance the NIAAA by charging fees for applications and labels. However, by 2001, the protocol was decommissioned due to mismanagement and lack of funds.

2006 saw a Product Authenticity Forum in another attempt to protect the significant Australian export industry of First Nations art. Research has shown that the $700 million tourism gift market prefers functional gifts that tell a story and are Australian-made. But to date the market is without a label that provides security.

Chemical code protects First Nations paintings

In an attempt to introduce a secure mechanism to identify original First Nations paintings a secret chemical code has been painted into an Aboriginal art work to outwit forgers who prey on Indigenous artists.

In the process chemical 'fingerprints' are mixed into each ochre that an artist uses to create their painting. The world's first chemically protected Indigenous artwork is Kimberley artist Freddie Timms' "Wunubi Spring" which he created in September 2008. The combination of all fingerprints is unique and helps experts identify the painting.

The chemical fingerprint cannot be entirely removed or seen with the naked eye. It can also be applied to existing paintings or their canvas.

The chemical technique was created by Rachel Green, a forensic science researcher at the University of Western Australia.

"Five different colours have been encoded differently, so they're quite chemically unique," Ms Green said. [15] "They can't be reproduced."

The new technique is hoped to help identify art works which are produced in Europe, imported into Australia and then taken into First Nations communities where artists paint some parts of them to claim them as their own [1].

An Aboriginal anti-theft system

In 2007 the Ceduna Aboriginal Arts and Cultural Centre became the first Aboriginal arts centre in South Australia to authenticate a First Nations artwork with new technology designed to safeguard art against counterfeiters and thieves [16].

Once the artwork has been tagged the details are saved and fed into a catalogue of Aboriginal art throughout Australia.

The system is called IDENTEart and authenticates an artwork with a microdot tag provided by First Nations-owned company Datadot DNA.

Respecting cultural values

A label of authenticity serves not only the buyer to know that First Nations people have crafted this art, it also serves the First Nations peoples.

The symbols and motifs used in First Nations designs also hold cultural significance for a particular group. Exploitation of the design impacts not only on the artist but also on the group.

Even if it is First Nations artists who paint, they have to obtain permission to use icons and symbols of other First Nations painters. "[My mother] showed me her artworks and the icons she used," says Noongar artist Jo Stuurman [17]. "I was given permission to use those icons in my artwork, which is very important in validating your artwork and giving it spiritual meaning."

First Nations art protocol guides

The Australia Council for the Arts supports Australia's arts through funding. It has a suite of five protocol guides that addresses moral, ethical and legal considerations when dealing with First Nations arts.

The five booklets cover media arts, music, performing arts, visual arts and writing, and are relevant to anyone working in or with the Indigenous arts sector - including artists, government, media, galleries and teachers.

The protocol guides endorse First Nations cultural and intellectual property rights that are also confirmed in the 2006 United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Each of the guides includes case studies of best practice and a checklist of key points for readers to consider. They are available for download at www.australiacouncil.gov.au.

The Indigenous Australian Art Commercial Code of Conduct deals with issues around Aboriginal art such as

- identifying the artwork's community of origin,

- community consultation to establish their custodianship of secret and sacred objects,

- organising repatriation of objects,

- developing and implementing appropriate policies for the handling of secret and sacred material, and

- the role of galleries, dealers and collectors.

Story: "Everyone else does it"

An Aboriginal woman visits India. She comes across a skinny dread-headed man with an Indian guy carrying a didgeridoo [18].

[Aboriginal woman asks:] "Hey mate where did you get that?"

"Oh, I made it."

"Yep, I'm sure you did. Who taught you how to play it?"

"I taught myself."

"Have you ever been to Australia?"

"No."

"Have you ever met any Aboriginal people?"

"No, why?"

[The skinny man enters the conversation.] "Yeah, we paint them and sell them in the street. We give lessons too. If you want to learn how to play one we'll be back there in an hour."

"Well, sorry, no, I don't. And actually they are a men's instrument and women aren't supposed to play them. It's very disrespectful."

"No it isn't."

"Oh believe me, yes it is, and I think I know."

"Why would you know?"

"Believe it or not I am actually Aboriginal, that's why. So you are painting them, selling them, giving lessons on them without any permission and knowledge or experience of Australian Aboriginal culture at all."

"Well everyone else does it."

"Right mate, yep that makes it okay."

Voices of First Nations artists

Responses by First Nations artists to a petition [19] which aimed to ban the import of art not made by First Nations peoples:

As an Aboriginal artist I strongly protest against the appropriation of Aboriginal totems and motifs for use in the tourist trade as this seriously undermines the integrity of Aboriginal art. To depict something as "Aboriginal style" is a violation of the integrity of Aboriginal artists.

— Janelle Evansk, Brisbane, QLD

As Chair of the QLD Indigenous Arts Marketing & Export Agency within Department of State Development Trade & Innovation I fully support this initiative. We must protect Indigenous Australian art and cultural products [...]. It is [...] an ethical and spiritual requirement that we do so!

— Debra Bennet, QLD

I work in Aboriginal health, I am an Aboriginal registered nurse and artist, I have seen the enormous health benefits that exist for my people with art in their own culture. Art is an expression of self & healing for my patients, family and friends who use art for healing, empowerment and economics.

— Sylvia Lockyer, Port Hedland, WA