Arts

Copyright of Aboriginal art

Copyright of Aboriginal art is immediate, but many disregard it and profit from copyrighted works. Copyrighting traditional works is particularly challenging.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

All Aboriginal art is copyrighted

The moment an Aboriginal artist or author creates a work it is protected under the Australian Copyright Act 1968. [1] Any subsequent sale of the work does not automatically endorse the copyright which remains with the author unless they decide otherwise.

Copyright generally protects an artwork from being copied during the lifetime of an artist and for 70 years after death.

But this has been "casually disregarded" [2] for decades as businesses and non-Aboriginal people assumed that "it was only Aboriginal art" and they didn't think they had to ask anybody. [3]

Even products that don't copy Aboriginal art but are "inspired" by it can get you into trouble, as ceramics brand Villeroy & Boch found out. The co-chair of the Indigenous Art Code deemed the design of the company's Rock Desert tableware line a cultural "misappropriation", while the company claimed the "creative interpretation ... intended no disrespect". [4]

British company, Derek Productions, used an unauthorised copy of a painting by Aboriginal artist Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri in the first series of After Life which aired on Netflix in 2019. The painting featured prominently on the main character’s living room wall. The company had to pay compensation and retrospective license fees for its use of the copy. [5]

Case study: Stolen & copied for profit, available still today

A well-known case of copyright violation is also a good example of how hard it is to get rid of the plagiarised version once it has entered the market.

In 1925 Angus and Robertson published Myths and Legends of the Australian Aborigines, a book written by Scottish author, William Ramsay Smith, which contained 29 pieces of writing. [2]

But Smith hadn't written the texts. He had copied as much as 90% from the original manuscript written by David Unaipon, the man featured on Australia's 50-dollar note and widely regarded as an 'Aboriginal Leonardo da Vinci'. Unaipon's name didn't appear anywhere in the book, except where he is mentioned in passing as a 'narrator'.

University of Technology researchers discovered that David Unaipon was paid just 150 British Pounds by Angus and Robertson [2], about A$15,130 in today's money. [6]

Ramsay's copyright violation was exposed in 1998, but, as of the time of writing, his books are still readily available on Amazon, both as paperback and Kindle versions, without any acknowledgement of the manuscript's original author. It's rating of 4.7 out of 5 stars is testimony to Unaipon's work and not Ramsay's.

Sadly, only a minority of publishers, such as Melbourne University Publishing, expose the theft and acknowledge the original author.

Case study: The long fight for Albert Namatjira's copyrights

World-famous Aboriginal painter Albert Namatjira entered into a copyright agreement with publishing company Legend Press in 1957. The company gained exclusive rights to reproduce his paintings [7], for example on greeting cards and tea towels or in books. At this time Namatjira still owned his copyrights. [8]

After Namatjira passed on two years later, his will left his estate including his copyright to his family. The Public Trustee for the Northern Territory government took on administration of his estate, with Legend Press continuing to manage copyright and paying royalties to the Namatjira family.

When the agreement concluded in 1983, the Public Trustee decided to sell the copyright to all his works to Legend Press without consulting Namatjira’s family. This ended their income from royalties.

For the following 34 years, the Namatjira family fought for the return of the copyrights.

In October 2017, Australian millionaire Dick Smith contacted Legend Press owner John Brackenreg's son Philip who agreed to transfer the entire copyright back to the family. [9]

While the copyrights changed hands for a symbolic one dollar, the NT government had to pay an undisclosed landmark compensation sum in August 2018 over the sale of copyright to Namatjira's works of art in 1983.

Agencies help enforce copyright fees

Aboriginal artists can decide to have a copyright collecting agency represent them. This means that the agency holds images of the artist's work in a database. Clients of this agency can then license the use of art by paying a licensing fee to the agency. The artist receives this fee less any administration costs of the agency. This way the Aboriginal artist does not need to negotiate or liaise with clients directly, making them less vulnerable to exploitation or breach of copyright.

The copyright collecting agency for Australia is called Copyright Agency. It's a not-for-profit organisation with more than 30,000 members: authors, journalists, publishers, surveyors, visual artists, photographers, cartoonists and illustrators. The Agency collects and pays royalties to creators and advocates for their rights. It facilitates consumers to use, share and reproduce content so they don't have to locate copyright owners or negotiate fees.

You should never give away your copyright… Because when I look at my art, I look at my family. So don't deal with anyone who doesn't respect you, who doesn't take on board your cultural needs, your family needs.

— Bronwyn Bancroft, Aboriginal artist [3]

Copyrights fail traditional art

Copyright for Aboriginal works is limited and does not protect oral culture [10]. Copyright law only extends 70 years after an author’s death and a patent only protects inventions for 20 years, which makes it very hard to sue someone who has misused traditional knowledge.

And Aboriginal knowledge doesn't fit into either category. Authors of traditional stories might not be known since some stories are very old and don't have an owner, but only a keeper. Who should receive the royalties?

Adding complexity to the topic is the Western law which assigns rights to individuals, whilst Aboriginal law recognises custodianship mainly by the community, governed by Elders who can make decisions to protect and use these resources. [11]

The copyright creation and moral rights of a documentary film, for example, would belong to the director and the producer, but not to an Aboriginal family who might have contributed significantly to the film's storyline.

The oral tradition or performance of a dance is not protected either, leaving it vulnerable to choreographers using them to create a new dance and owning the rights of the new work.

"A traditional dance is in that fuzzy ground where it's too old for copyright protection," explains Aboriginal lawyer Terri Janke [10]. If an Aboriginal dance group is filmed, "there is a separate copyright in the film that belongs to the film-maker, often not the Indigenous dance group," she says.

Care should be taken not to copy designs found in Aboriginal art work of any kind. When a group of didgeridoo players in the US published images of a didgeridoo-playing man along with a Dreaming story on their website they offended the traditional owners.

The man's body paintings showed traditional designs which were "effectively private 'signatures'" relating to specific country. Such designs belong to individual clans, are part of their identities and cannot be borrowed or imitated. New designs should also not be made up [12].

Sharing a traditional story also offended the elders. Such stories belong to clans and are theirs to tell.

However, copyright laws did not cover the case. An Aboriginal lawyer specialising in intellectual property commented that copyright laws would only have been breached if the group had performed – without permission and attribution – songs that had been formally registered for copyright [12]. Singing ancient traditional songs would not breach copyright either as they are older than 70 years, but it would disrespect Aboriginal protocol.

The same applies for using Australian plants with medicinal properties. No-one stops overseas companies from exploiting traditional knowledge they gained in Australia, taking it overseas, creating products from it and selling them for profit.

That's part of the problem, people can do that [disrespecting Aboriginal protocol] and not infringe copyright laws, but you can see how offensive it is to Indigenous people.

— Terri Janke, Aboriginal lawyer [12]

A grand for a dollar: The missing compensation

The following story [13] is a good example of how Aboriginal copyrights were overlooked, but also an example of how to make good past mistakes.

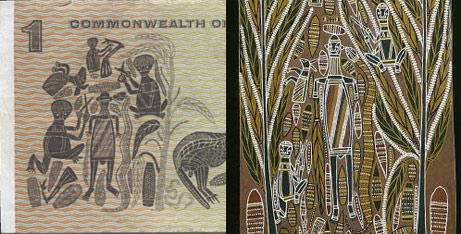

Gordon Andrews was the designer of Australia's first decimal $1 dollar note. On the backside of the note he introduced designs based on Aboriginal rock carvings and the photograph of a bark painting by Manarrngu artist David Malangi Daymirringu from Arnhem Land, NT.

The photo had been taken by Czech artist Karel Kupka during his studies of Aboriginal art in Arnhem Land and made available to designers entering the competition for the banknote's design.

While there was no copyright infringement with the photograph, there was with the painting. But this advice came too late, the banknotes were already being printed, and a redesign would have been extremely costly.

The Reserve Bank of Australia, the issuer of the banknote, had requested that Kupka provide the name of the artist to the Bank. Less than a month before the note was issued, the artist’s identity was provided to the Bank. The Governor of the Reserve Bank, Dr H C Coombs, renowned for his passion for Aboriginal people, paid Malangi $1,000 (around $12,600 in today's money and consistent with fees paid to other artists).

Coombs travelled to the Northern Territory a few months later to meet Malangi, where he presented him with a specially struck medallion commemorating his contribution to the design and a personal gift of fishing tackle, as David Malangi had requested. The episode was an important step in recognising Aboriginal painters as artists entitled to copyright.

Video: The story of the painting in the $1 dollar note

The video tells David Malangi's side of the story and explains details of the artwork that depicts the "mortuary feast" of one of the artist's creation ancestors, Gunmirringu, the great ancestral hunter. The Manarrngu people attribute this story as the origin of their mortuary rites.

For his role in the design of the $1 bill David Malangi became known as "Dollar Dave". [14]