Arts

Aboriginal art: More than dot paintings

If you associate Aboriginal art with dot paintings you limit yourself. Beyond the dots is a universe of art as diverse as its artists.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

Aboriginal art is as diverse as its creators

You only need to walk into a souvenir shop to find that Aboriginal art seems to equal any object painted with dots. But nothing could be further from the truth.

The dot style only emerged in the early 1970s from the remote Northern Territory community of Papunya. It's a tiny fraction of the art styles and media available to contemporary Aboriginal artists.

Here are examples of what Aboriginal art is also about:

- Dance. Today dance can be traditional, contemporary or both. Audiences around the world love the world-class Bangarra Dance Theatre or the Northern Territory Chooky Dancers' interpretation of Zorba the Greek.

- Visual arts and craft. These include pottery, textile-based art, weaving, jewellery, ceramics, wood carving, miniature carvings, grass weaving (tjanpi), shell stringing (see below), glass work and Aboriginal films. New media artists work ghost nets into artworks, paint skateboards or create dilly bags from scrap metal.

- Theatre. There are several Aboriginal theatres, some operated as early as the 1970s.

- Language. Art around language includes Aboriginal music and storytelling.

- Lore. Lore is the 'body of knowledge' passed on through storytelling in its various forms.

- Photography. Several Aboriginal photographers have made a career in the professional market.

- Ceremony. Artists perform both traditional and contemporary ceremonies, and not only for tourists (see Welcome to Country).

Visual arts and crafts are the most popular Aboriginal art forms, followed by dance and then theatre. [1]

Can Aboriginal art be contemporary?

Of course! But not only many art lovers assume that Aboriginal art depicts traditional themes on traditional media. Many museums around the world only now realise that Aboriginal artists are also making contemporary art, far from what curators understood to be "Aboriginal".

Aboriginal art evolves just as its creators. It is only natural that Aboriginal artists continue to depict and interpret their traditional heritage, stories and places in ways that are innovative and experimental and thus contemporary.

It is a stereotype that "Aboriginal" cannot go together with "contemporary".

There’s that expectation from people that know nothing about Aboriginal culture that they’re going to get some kind of traditional experience rather than the contemporary experience.

— Sam Yates, Manager of Arts and Cultural Development, Country Arts South Australia [2]

Story telling sets Aboriginal art apart

Storytelling is at the core of Aboriginal art in all its manifestations. Whether it's visual art, dance or film, "storytelling is the mother of all those mediums", says Stephen Page, artistic director of the Bangarra Dance Theatre. [3] "It's a huge part of our cultural fabric. There is a great confidence and pride about black practitioners telling their stories in whatever medium."

"The thing that sets Aboriginal art apart is the story," says Gurindji artist Sarrita King. [4] "I don't think that the story will ever leave Aboriginal art. When you walk into an Aboriginal art gallery, it's like you're walking into a book. You're walking into knowledge, into a beautiful picture book where every image you see has a soul."

Seith Fourmile, from the Djumbunji Press in Cairns (Queensland), explains that development on land does not affect its stories. "When we talk about story, just remember that even though buildings might sit on country, our country is still the same underneath and those stories are still the same."

"They'll never die, they've been there a long time and they'll still be there when we pass on. The thing is trying to keep that tradition going and that culture and stories strong."

The experience of [taking part in a men's ceremony and] sitting down, recuperating, looking at and being told about the landscape in a totally different way changed me as an artist... I found new significance in all of those [natural] elements and how they relate to us as people. Everything has significance.

— Sam Juparulla Wickman, Aboriginal artist [5]

New media artists

But Aboriginal art does not stop with cultural practices. Contemporary, young Aboriginal artists take it into the new millennium and become Aboriginal new media artists.

Karen Casey is such an Indigenous new media artist. Descended from the Pydairrerme people of the Tasman Peninsula, she created Art of Mind in 2004. A computer program lets the audience see the artist's brain activity. "In Art of Mind, I focus on my inner connection with the land and with others and on promoting reconciliation and people coming together. People genuinely want to make a connection, to be on the same 'wavelength' and this is what we explore," says Karen. [6]

When Kimberley artist Ngarra, born around 1920, found that the monsoonal heat made ochre painting practically impossible he instead used Texta (an Australian brand name for coloured felt pens), Ngarra invented a variety of original and intricate techniques. [7]

Indigenous art in Australia is becoming a subset of the mainstream art space: defined by race and by its concerns, but less and less distinct in its methods and techniques.

— Nicolas Rothwell, The Australian [8]

The didgeridoo is known by more than 200 names. Yidaki is the first and oldest name whose origin is Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory. 'Didgeridoo' is the name white people gave the instrument after hearing its sound.

Story: The Tjanpi Desert Weavers

The Tjanpi Desert Weavers are among the recent success stories of the Aboriginal art industry. [9]

The Ngaanyatjarra Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Women's Council (NPYWC) founded the collective in 1995.

More than 300 Aboriginal women from 28 remote communities in the western and central deserts of Australia come together to create their art, work, sing and swap stories. The process has encouraged these artists to make large, ambitious sculptures.

Their best-known piece is probably the Tjanpi Grass Toyota, which won the 2005 Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award.

"We should be viewing the Tjanpi Desert Weavers as true innovators of contemporary art. The work that they do lies at the heart of Aboriginal art and culture. They are insightful artists who work within a community context with materials readily available to them such as colourful wools, chicken wire and grasses. They are able to be inspired by techniques handed down through the generations and innovate upon them, fusing them with their lived experiences of the 21st century." [10]

Aboriginal fashion emerges

Who would have thought that one Aboriginal fashion label dates back to 1969 when a Christian missionary helped start it on the Tiwi Islands?

With the assistance of Sister Eucharia a group of Tiwi women from Bathurst Island created their own clothing label – Bima Wear – and in 2019 some of those who helped start the Aboriginal owned and operated business were still working there. They design, print and manufacture everyday, occasion and ceremonial wear that celebrates Tiwi language and culture. [11]

Bima Wear is an exception. Most Aboriginal fashion businesses, despite plenty of talent, are little known beyond the boundaries of the communities they operate in. [12]

For their communities fashion businesses bring plenty of benefits, for example employment and investment. Consumers enjoy designs that are enriched with story, meaning and purpose.

Collaborations between mainstream brands and Aboriginal fashion labels needs cultural awareness and consultation, as well as respect and fair pay. This can be an intimidating steep learning curve as Lisa Gorman, founder of fashion label Gorman, found out. "I was hesitant because of the cultural sensitivities and worried whether I would be able to pull it off or get criticism for cultural misappropriation," she reveals. [12] By putting the rights of Aboriginal artists at the core of the company's licensing agreement she was able to successfully collaborate with Mangkaja Arts from the Kimberley.

As a consumer it pays to be aware of the design's origin and meaning. "Some stories are not appropriate to be worn," says Dave Giles-Kaye, CEO of the Australian Fashion Council. "You don't want to be misappropriating the meaning of something by wearing it in the wrong situation." [12]

Once challenge unique to Aboriginal models comes from the emphasis on community rather than the individual. Models can feel "that they're showing off by modelling", and this might make attracting new talent hard. [12]

To see more Aboriginal fashion, follow @ausindigenousfashion on Instagram.

In 2018, Awabakal woman Charlee Fraser ranked as one of the Top 50 fashion models and was the most booked model of the spring New York Fashion Week that year. [12]

Homework: "Where are the Indigenous models?"

During a visit to Australia in 2000, model Naomi Campbell asked: "Where are the Indigenous models?"

Your homework is to find the names and achievements of at least 5 Aboriginal fashion models.

Email me once you've found them!

Tjuringas: sacred objects for the initiated

In September 2011 the sale of a tjuringa at an auction house in Britain made headlines in Australia.

Tjuringa is a term generally meaning 'sacred object' and 'sacred practice'. [13] It was used by the Central Australian Arrernte people as a prefix when speaking about many sacred items, including headdresses, poles, bullroarers, earth mounds, ground paintings and incised stones and wooden boards. They also used it in reference to traditions, rituals, ceremonies, songs and stories.

In its broad sense tjuringa (also spelled 'churinga') is mostly used for sacred incised and/or painted boards or stones many Aboriginal groups (not only the Arrernte) have made.

Tjuringas may be used in rituals to represent ancestral beings or protect the carrier from harm. Others are deeply personal objects symbolising the essence of the owner's individual spiritual being. If the owner dies their family stores the tjuringa in a safe place. Death was the punishment if someone broke a tjuringa, or let unauthorised people (for example women) see one. [13] Only initiated, long-term male members of a clan were allowed to see and handle tjuringas.

After protests the auction house withdrew the tjuringa from sale. However, several wooden tjuringas were still on sale on eBay. [14]

Aboriginal artist designs coins

Aboriginal artist Darryl Bellotti designed the Perth Mint's Dreaming coins, a series of 45 coins which the mint issued from January 2009 to 2011.

The gold, silver and platinum coins feature different interpretations of Australian animals like kangaroo, dolphin, king brown snake, brolga and echidna. It is the first time one artist has designed an entire coin series.

"In ancient times boya, or money in Nyoongar culture, represented the tradeable commodities of rocks, stones of quartz and granite, and naturally occurring specimens of precious metals," explains Perth Mint Chief Executive Ed Harbuz. [15]

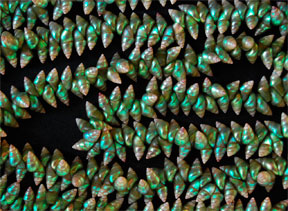

The dying art of shell stringing

Shell stringing, along with mutton birding (the seasonal harvesting of the chicks of petrels) and basket weaving, is one of the few Tasmanian Aboriginal traditions that has continued unbroken. [16]

But only a handful of Aboriginal artists continue the practice of stringing tiny, brilliantly coloured maireeners (rainbow kelp) and other shells. It is an art form restricted to women.

The highly-prized necklaces grace Aboriginal displays in museums around the world and come with four-figure price tags in galleries. [17]

To create a necklace from shells Aboriginal artists require intimate knowledge of shell locations, the tides and maritime seasons. Collection depends on a multitude of factors, and artists often wade in waist-deep water to retrieve the shells from the kelp beds. [18] The harvesting season lasts from November to April.

After collection the shell preparation – usually done in winter – takes six to nine months: cleaning, drying, sorting, making the holes, stringing and then oiling them for an iridescent shine—a tedious process, given their size.

Then comes the stringing of up to 700 maireeners, a time-consuming process. Each shell is handled eight to nine times.

Two such shell stringing artists are Aunty Corrie Fullard from Hobart, and Lola Greeno from Cape Barren Island. Their necklaces are displayed in museums and private collections throughout Australia.

Embedded in every stitch and thread and string there is a story.

— Helen Anu, curator at the Australian National Maritime Museum [18]

Pukomani poles

Aboriginal artists create Pukomani poles from wooden logs. They carve and paint them with red, yellow and white ochre.

Traditionally Pukomani poles were created after the death of a person and used for ceremony (dancing, singing and crying). The in-laws of the person who died commissioned and paid for them with ornaments and food, more recently with money.

Pukomani poles act as headstones around the grave. A figure at the top of the pole represents the spirit who did the first ceremony.

Today artists create Pukomani poles only for galleries. They are no longer part of contemporary Aboriginal life. [19]