Law & justice

Juvenile detention

Aboriginal youth are overrepresented in jails. Detention statistics make experts talk about a "state crisis". High detention rates have many causes. Being at the wrong place at the wrong time is sometimes enough.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

Selected statistics

-

100% - Percentage of children in detention in the NT who are Aboriginal. [1] Percentage of the NT population who are Aboriginal: 30%. [2]

- $630

- Daily cost to keep a young Aboriginal person in juvenile detention. [3]

- 43

- Times an Aboriginal juvenile in Western Australia is more likely to be detained than non-Aboriginal juveniles. [4] Same rate for all of Australia in 2013: 31 times, [5] in 2008: 28 times, [6] in 1994: 17 times. [5]

-

46% - Proportion of male juveniles in detention in Australia who are Aboriginal. [7]

-

57% - Proportion of female juveniles in detention in Australia who are Aboriginal. [7]

-

90% - Percentage of Aboriginal juvenile offenders who reappear in adult court; same figure for non-Aboriginal youth: 52%. [8]

- 28

- Times an Aboriginal male child is more likely to be placed in juvenile detention than a non-Aboriginal child. [9] The rate for female children is 24 times. [10]

-

54% - Percentage of juveniles detained in Australia who are Aboriginal. [11] Same figure for WA: 74%; [12] for NT: 96%; [13] for NSW: 56%. [14] Proportion of Aboriginal kids of all 10- to 17-year-olds in Australia: 6%. [11]

-

20% - Increase in juvenile detention rates of Aboriginal youth (10 to 17 years old) in 2009-10 compared to the previous year. [15]

-

27% - Increase in Aboriginal juvenile detention rate nationally between 2001 and 2007. [16]

- 250

- Number of Aboriginal youth in north-western NSW who have been sentenced to juvenile prison terms in 2008-2012. Same number for non-Aboriginal youth: 12. [5]

-

81% - Proportion of women in juvenile detention in NSW who have been abused or neglected. Proportion of men: 57%. [17]

-

73% - Chance that an Aboriginal child would be warned or charged by police by the age of 23. [18]

- 10

- Current age of criminal responsibility in Australia, New Zealand and the UK; in Germany, China and South Korea: 14. [19]

-

80% - Percentage of all incarcerated 10-year-olds in 2020 who were Aboriginal. [11]

Juvenile detention statistics

Up to 70% of detained children were remanded simply for breaching bail conditions, and the time on remand is getting longer and longer. [20] In 2009 around 300 juveniles were arrested for breach of bail each month, up from about 100 in 2000.

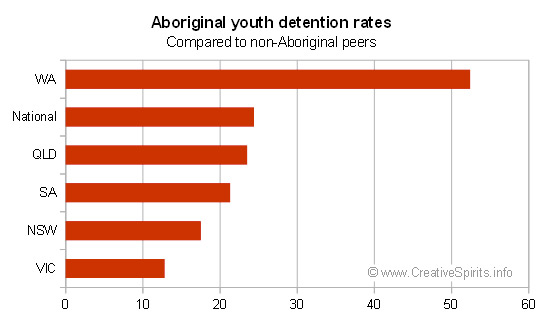

Aboriginal children and teenagers are 24 times more likely to be incarcerated than their non-Aboriginal peers, and more than twice that rate in Western Australia. [21] The gap in incarceration rates has grown every year since 2010-11.

There is a greater likelihood of an Aboriginal child being incarcerated than completing year 12 schooling. [18]

While young Aboriginal people make up only 6% of the population, 58% of young people in prison are Aboriginal. [21]

Of the people aged 10 to 17 in detention or community-based supervision, 12.6 per 10,000 people are non-Aboriginal, but 15 times as many, or 189 per 10,000, are Aboriginal. [21]

But study after study shows that contact with the criminal justice system at a young age can do lasting damage to children, their families and communities. Almost all (94%) of children in detention aged 10 to 12 return to prison before they are 18, setting them up to end up in an adult prison before they turn 22. [11]

Legal experts label the overwhelming over-representation of Aboriginal youth a "state crisis", [22] and even the Western Australian police commissioner believes that "there’s a vast volume of them [young people] where it does not make any sense to take them away from country". [23]

Our youth languish in detention in obscene numbers. They should be our hope for the future.

— From the Uluru Statement From the Heart

Why are so many kids in juvenile detention?

The high youth detention rates have several causes: [5][24][21][11]

- Out-of-home care. Studies show a strong link between the time children spend in out-of-home care and juvenile detention. Aboriginal children are overrepresented in the out-of-home care system in every jurisdiction in Australia.

- Low age of criminal responsibility. Increasing the minimum age of criminal responsibility from 10 to 14 could lead to a decrease of about 15% in the number of young Aboriginal people in detention. [25]

- Breach of rules and laws, for example, not complying with a curfew.

- Unaccompanied, not being in the company of a parent.

- Social disadvantage. The most disadvantaged youths are 7 times more likely to be under supervision than the most advantaged.

- Unrepresented, e.g. due to lack of access to a magistrate or because there are only limited regional justice services available.

- Punitive state governments. Examples include mandatory sentencing in Western Australia, the removal of the principle of imprisonment as a last resort in Queensland, and the abolition of youth drug courts in Queensland and NSW.

- No bail. No-one can provide bail because they are out of country.

- Heavy-handed courts which hand out the "harshest sentences for stealing ever recorded by juveniles". [24]

- Heavy-handed police who arrest juveniles because they are Aboriginal ("over-policing") or strip-search them – some as young as 11 – in significantly higher numbers. NSW police are known to have a secretive blacklist that targets mainly Aboriginal children.

- Wrong lessons learned as a child. "In their early lives, kids need repetition, they need routine, they need security – it's when kids learn whether they need to hug or to slap," says Dr Cashmore, a Sydney University child abuse expert. [17] "If you're exposed to violence at a young age, you can learn that that's the way to engage with people. Or you might turn to drugs and alcohol as a form of self-medication for the emotional pain or anger you're experiencing. Then offending may become the way of maintaining that habit."

- Wrong treatment 'inside'. If young offenders are held in solitary confinement for too long it puts them back on a perpetual destructive cycle of reoffending.

- Racism. "On a number of occasions I have witnessed officers abusing and yelling at Aboriginal men in here and putting them down because they can't speak English properly, and that's not fair and needs to stop," says Dr Cashmore. [17]

- Overdue reforms and change. Despite a royal commission into juvenile detention from July 2016 to November 2017 with more than 200 recommendations not much has changed. "Nobody is prepared to just trust experts and implement legislation," says a weary Marty Aust, president of the NT criminal lawyers association. "I’m tired. I’m exhausted. [...] Sick of 70-hour weeks, sick of youth crime, and we’re sick of victims of crime." [1]

"The causes of the horrendous rate of Aboriginal juvenile over-representation are complex but in the rural and remote parts of the state, sustained and targeted policing and draconian sentencing trends are playing an undeniable role," says Stephen Lawrence, principal solicitor with the Aboriginal Legal Service in NSW. [5]

"We have intergenerational trauma. We have the consequences of family violence, with young people preferring to be on the street than at home. We have ongoing problems with a lack of engagement with the education system. We have high rates of youth suicide," adds University of Western Australia criminologist Prof Harry Blagg. [21]

Many cases don't lead to a conviction or custodial sentence. Corey Brough spent 29 months in jail without being convicted of a crime. [26] Although recommended by the United Nations, he received no compensation for the time he spent while refused bail and little support to help him settle back into the community. "I feel violated," Mr Brough says, "They can break the law and get away with it."

For many young Aboriginal men in rural communities, detention has become a rite of passage. [8]

If youth receive multiple charges it can expose them to harsh mandatory sentencing.

Locking us up is not really helping. It's just making us do more stuff like that.

— Nathan", 17, detained in Grafton, NSW [22]

There are no votes in black matters, so no one cares.

— John McKenzie, chief legal officer, Aboriginal Legal Service, about politicians' response [22]

Detention reality: No mattress, no sheets, no clothes

A 2018 study of children in detention in Western Australia found that almost every child was "severely impaired" in at least one brain function (e.g. memory, language, attention or executive function) which limited their ability to plan and understand consequences. The study found that nine out of 10 kids had some cognitive impairment, and one in three had foetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Three quarters of the kids were Aboriginal. [11]

Australians didn't know much about what happened in detention until the exposure of the treatment of Dylan Voller on national television.

Dylan, a youth detained in Darwin's Don Dale Youth Detention Centre, sparked a royal commission in 2016. Images of him strapped to a chair wearing a hood while in the notorious detention centre shocked many when they were screened by ABC’s Four Corners.

When giving evidence Mr Voller revealed the appalling conditions in detention to the commission: [27]

- No food. Detainees are regularly denied access to food and water as punishment for bad behaviour.

- No toilet access. For the same reason, guards deny access to toilets. “There was one instance where I was in an isolation placement at Alice Springs detention centre and I was busting to go to the toilet ... They’d just been saying ‘no’ [for more than 5 hours]. I ended up having to defecate into a pillow case because they wouldn’t let me out to go to the toilet."

- Bullying by guards. “I’d go to the toilet, they’d only rip off, like, five tiny little squares of toilet paper and say: ‘That’s all you’re getting ... make it last’.”

- Shared underwear. “If you don’t buy your own underwear, the only other underwear you have the choice of wearing is the underwear everyone else wears. It gets washed, you pick out another pair, it gets washed and it goes through all of the males in Don Dale.”

- Strip searches, stripped naked. Mr Voller said he was regularly strip-searched and on one occasion left in a cell overnight with no mattress, sheets or clothes. “They turned the aircon on full blast, I was freezing all night,” he said.

- Guards tell lies. In a stunning similarity to what was told to members of the Stolen Generations, guards lied to Mr Voller about his family: “I had one case worker I remember that was saying my family didn’t really care about me and stuff like that,” Mr Voller said through tears. “For a long time I started believing it.”

Solitary confinement is another detention reality. Children are placed into small, windowless cells the size of a parking space – called an "intensive support unit" or ISU – officially for a limited time, but frequently far longer, sometimes 14 days. They remain inside the cell for up to 23 hours a day, with no TV, no school and no human interaction. Such treatment constitutes torture under human rights law. [28]

I was like hell scared. I was in the corner rocking back and forth. My throat was hurting, it was hard to swallow. My chest felt like it was caved in … I cried for like the whole night.

— 'Louie' recounting his first night in juvenile detention [28]

Can detention have benefits?

Detention might appear promising to some who are homeless and sleep rough. The young people get at least three meals a day, a change of clothes and a rest. [11]

Some say detention time can foster stronger links with Aboriginal identity. [22]

Dubbo police inspector, Rod Blackman, believes there is no deterrent for youth facing jail time. On the contrary, jails are operating as safehouses for vulnerable children and the criminal justice system is becoming a proxy social service provider [5].

I've lost count of the number of children who when they are finally refused bail and end up in our juvenile detention centre, are quite happy because they know they're going to get fed three times a day, and they know they're in a safe environment, and quite often they've got other family members in there.

— Rod Blackman, Dubbo police inspector [5]

What could help?

Instead of locking Aboriginal children in juvenile detention community justice arrangements such as circle sentencing or the youth Koori court are a proven way to prevent them ending up in custody. [11]

In these programs magistrates work with Aboriginal Elders, police, victims and the offender’s family to determine an appropriate sentence.

But ultimately programs are needed that prevent Aboriginal youth to go to detention or jail in the first place. Such programs might include therapy, social support services and diversion away from the justice system and engaging with the Aboriginal community.

Linking children up with mentors also helps communities, and one such program reduced juvenile robberies in its first year by 80%. [29]

Alternatives to detention include warnings, cautions and a youth justice conference – where the young person meets with the police and their victim. [29]

Story: Wrong time, wrong place for Aboriginal teenager

This is a true story, reported in the Sun Herald [30].

"It was a case of wrong place, wrong time, when a 16-year-old boy from a prominent Sydney Aboriginal family turned up at a party to see if his cousin was OK after he heard there had been a fight in which someone had been stabbed.

Partygoers at the Maroubra function last August called police but by the time 30 officers arrived, the alleged offender had left the scene.

Enter the 16-year-old, who found himself struck around the legs with a baton and given a burst of capsicum spray, allegedly for attempting to enter a crime scene.

Parramatta Children's Court magistrate Mark Buscombe was told by the teenager's barrister, Philip Adams, that the youth was arrested and taken to Maroubra Police Station where he was strip-searched without a guardian being present.

The court heard that police then took the teenager to hospital and released him but arrested him again the next day and charged him with failing to obey a police direction, offensive language, resisting arrest and affray. Mr Adams said there was no record of the arrest or detention of the teenager in the notes of officers who attended the scene.

In a judgement on July 2, Mr Buscombe dismissed all charges against the teenager, who pleaded not guilty. He also ordered police to pay his legal costs."