Law & justice

Tribal punishment, customary law & payback

Aboriginal tribal law is often seen as harsh and brutal, but it ensured order and discipline. Payback is the most known form of customary law. Payback is still practiced, conflicting with white law.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

What is payback?

Payback is a form of mostly physical, and sometimes deadly, punishment carried out by elders or victims to members of their group who broke the law. Payback is an important element of Aboriginal law; "where grievance exists, payback is expected". [1]

After an incident happened, the parties involved meet and negotiate a way to restore balance so that tribal or family relationships and friendships can continue. This included the wish of the victim party for retaliation and the wish of the offending party for paying the debt incurred. Acknowledging the right to punish is important because it prevents revenge attacks and further escalation of the conflict. [1]

The main purposes of payback are to restore peace, assist healing and help both parties to move on.

When a party agrees to payback they might have to make a gift or accept a physical punishment. These, along with marriage exchanges, ceremonial relationships and ritual helped create ties that also prevented further escalation.

Payback is a formal and organised way of punishment and usually happens in a controlled way where onlookers restrain the participants from being overly zealous when penalties are determined. [2]

Before invasion payback addressed crimes such as stealing (items or women), dating someone from the wrong tribe, crossing cultural boundaries without asking for permission or perceived sorcery. [3][1] After invasion payback was given to settlers who had abducted and assaulted Aboriginal women and was often deadly. [4]

Payback is still alive

We tend to assume that tribal law and payback are things of the past but they are far from that.

Phill Moncrieff, an Aboriginal musician, explains that "payback can be done anytime 24/7. It has no respect or alliance with the white man's law," [5] a fact that is hardly recognised. "Payback culture will always be unhindered by the white man's laws in some areas of Australia," he says.

"Quite often we have seen the white man's laws become useless and inadequate in handing out exact justice. So Ancient Law takes over. It is still alive in our country and we still manage it the way we have done for 40,000 years."

In Phill's country "there are numerous and ongoing payback [cases] operating, which sometimes never get resolved," which is a problem as he admits. Previously "tribal summits would be orchestarted to sort out these ongoing issues", many times successfully.

Payback is a big part of our law and culture.

— Phill Moncrieff, Aboriginal musician [5]

Law grounds

Traditionally Aboriginal law was decided in councils of men and they decided matters of the land and its boundaries. [6] These men met on law grounds which were usually within the boundaries of a tribes' country. Some of these law grounds however were on the boundary itself, hence accessible for both tribes. This enabled Aboriginal people of both tribes to meet together without crossing other people's lands.

Law grounds were used not only for councils but also to put young Aboriginal men and women through traditional law. If each parent was from a different tribal group they could decide between them where each child of theirs would be initiated and at which tribe's law ground. [7]

Story: The beginning of an initiation ceremony

Peter Stevens, a Kurrama man, remembers law meetings for initiation. [7]

"When there are law meetings for initiation, the starting procedure is for the ceremonies to start from the centre of the law ground. Say you've got a son to start the meeting, you must stay within the law ground boundary and start the ceremony there. If you go to the ceremony, you can't leave that law ground until everything connected with the initiation process is finished. As a father you are not allowed to go anywhere. All the fathers must sit there throughout the ceremony."

"The preparation for the ceremony starts with one boy going round to the communities bringing all of the mobs to the law ground for the opening. And this young boy and the others who are going through the law with him will come back to the centre of that law ground."

"The traditional method was that two boys at a time would go through the law together in accordance with their skin grouping, and in a relationship of skin which cannot be mixed up. These boys are said to be yarlbu to each other, which means that they have gone through initiation together."

"These days, with the loss of traditional land and culture, there is a lot of mixing up of skin grouping at these ceremonies, everybody is yarlbu now. Traditionally boys who were yarlbu were said to be like brothers-in-law, gumbarli. At the end of this meeting and when the ceremony is over, the people will decide where the next ceremony will be held, which law ground, and when."

Tribal punishments

Spearing

One of the traditional tribal punishments is spearing where the victim gets speared into the thigh or calf. This type of punishment is often shown in Aboriginal movies. The crime determined what kind of wound the offender received.

The most serious form of payback (prior to invasion) was a revenge expedition that set out to kill the offender ritually. [1]

Aboriginal man Henry Long knows a thing or two about receiving a spearing.

"I got speared in the leg, too, for being cheeky. I got hit on the head, too, by all my old people. The spear came out of the calf of the leg. My old father did that. I was a cheeky bloke fighting the other fellas over some silly things I been doing in my young days. I was going with the wrong girls. My skin group is Milangka. I was with someone from a wrong skin group...

"After you've taken your punishment then people don't worry about you." [8]

'Singing' a person

Being 'sung', sometimes also referred to as 'pointing the bone', is an Aboriginal custom where a powerful elder is believed to have the power to call on spirits to do ill to another Aboriginal person alleged to have committed a crime or otherwise abused their culture.

Singing a person might still be practices today. Paul Clune recounts an incident in Perth: [9]

"In March this year [2016] I sat and intermittently spoke for two hours beside a tribal man at Royal Perth Hospital who'd flown to Perth from Broome that morning. He was there because his 40-year-old large, long, tribal initiation chest scars had inexplicably and suddenly erupted into festering pus wounds.

"He and I gently acknowledged that he had more than likely been sung by a Featherfoot."

A 'featherfoot' (or kurdaitcha man in Arrernte) denotes a sorcerer in Aboriginal spirituality.

White lawyers and tribal law

The white, "new" law, and the traditional, "old" law can lead to problems when a court case is heard. How should the accused be punished? Which law should be followed, and to which degree?

Aboriginal people still follow and practice customary law, [10] but there is no law that binds lawyers and judges to take traditional law into consideration.

Jailing an offender prohibits properly controlled and sanctioned payback, and the unresolved incident remains simmering within the community, sometimes leading to a cycle of violence within the community.

Defence lawyers can specifically ask for their clients to be released on bail to face a tribal punishment. Since 1997 details of such payback are no longer provided as judges might opt to hold the offender for their own protection.

In one case a judge was informed how a man, "armed with only a small shield to defend himself, would be speared in both legs, punched in the face and chest, hit on the head with boomerangs and have boomerangs thrown at him". [11] The man was not released. Judges can dismiss requests for reduced sentences for the sake of tribal punishment[10] at their own discretion. Finding the right balance between white law and customary law can be a challenge. When a court sentenced a 55-year-old Aboriginal man who had intercourse with his 14-year-old promised bride the initial one-month jail term was revised to 18 months (excluding suspensions) because, in white law's terms, the man had still committed a serious sexual offence. [12]

Under conventional law, the widow of Yothu Yindi frontman Dr Yunupingu had the right to choose where to bury her husband. But under traditional law, other clan members decided. This led to a dispute which required mediation to reach agreement. [13]

Lawyers need to be careful not to pick one law over another to defend an Aboriginal client. Some Aboriginal people feel that "too many lawyers are only interested in the rights of the perpetrators" and use Aboriginal law to protect them from white law. [14] Traditional law would only be acknowledged if it suited the case of their client.

Aboriginal victims seem to matter more to lawyers when the perpetrator is white, not Aboriginal.

It is not somehow more acceptable to be raped, abused and murdered when the one doing it to you has the same colour skin.

— Bess Price, Aboriginal woman [14]

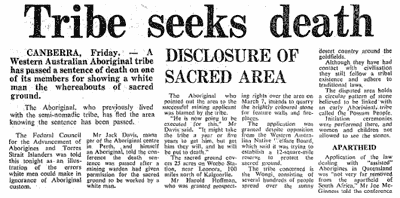

Aboriginal customary law in the media

The media loves to pick up a story where Aboriginal people ask for customary law to be applied and their demands seem – in white people's eyes – outrageous. Headlines don't really change between 1969 and 2002:

"Aborigine Asks Court to Spear Policeman to Death" (Reuters, 28 January 2002).

Should tribal law change?

Aboriginal people want to keep their culture, respect their ancestors and their law. This puts them into a dilemma: How does this fit into the contemporary legal world, and how can Aboriginal people also claim equality and human rights?

"We can't do that without changing the [traditional] law," says Aboriginal woman Bess Price. [14] "But we need to change it ourselves, others can't do that for us. Only we can solve our own problems and we will do it in our own way. But we really need the support of governments and our fellow citizens."

Mrs Price issues a challenge to lawyers.

"You need to find a way to listen to those who don't speak English, who are the most marginalised and victimised in our own communities.

"You need to listen to our own women and young people, the ones who don't have a voice under the old law.

"If you really want us to have human rights then you have to find ways to protect the victims of black crime as well as white crime."

But not all Aboriginal people agree to still observe tribal punishment. Alison Anderson, an Aboriginal woman and a former minister for Aboriginal affairs in the Northern Territory, opposes the return to tribal law.

"We have mainstream laws and we all have to abide by them," she says. "Our old laws were savage laws that existed at ta time when we ran the desert. I speak my languages and I keep my culture but that doesn't stop me living in the other [Western] world. What we want now is to move on." [15]