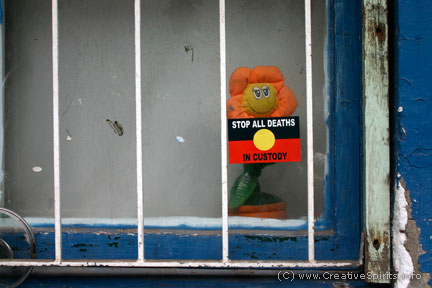

Law & justice

Royal Commission into Aboriginal deaths in custody

A royal commission in 1987 investigated Aboriginal deaths in custody over a 10-year period, giving over 330 recommendations. Its recommendations are still valid today, but very few have been implemented. Every year, Aboriginal people continue to die in custody.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

Selected statistics

- 115

- Deaths in custody in Australia from 2013 to 2014. [1] Same figure for 2000 to 2007: 701; for 1980 - 2000: 1442. [2]

- 492

- Aboriginal people who died in custody between 1980 and 2015, or close to 19% of all deaths in custody in that time. [1]

- 99

- Aboriginal deaths in custody in Australia from 1980 to 1989 which lead to the royal commission. [2]

- 15

- Number of Aboriginal deaths in custody in 2014 (25% of all deaths). [1]

-

18% - Percentage of men who died in custody between 1980 and 2000 who were Aboriginal. [2]

-

32% - Percentage of women who died in custody between 1980 and 2000 who were Aboriginal. [2]

-

2.8% - Percentage of Aboriginal people in the population of Australia.

- 3

- Factor by which deaths in custody in private prisons are higher to those in government-run prisons. Nationally they are twice as high. [3]

- 10

- Minutes a prisoner is allowed to see a General Practitioner (GP). [4]

- $50m

- Today's cost of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. [5]

-

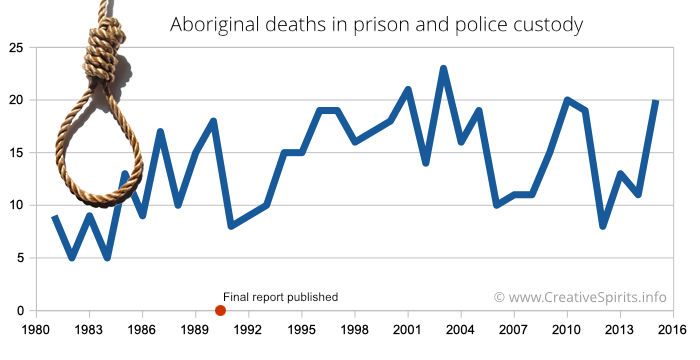

150% - Percentage by which Aboriginal deaths in custody went up since the Royal Commission in 1991. [6]

-

24% - Percentage of motor vehicle pursuit deaths since 1989 where the person was Aboriginal. [1]

-

38% - Proportion of Aboriginal deaths where medical care was required at some point, but not given. [7]

-

41% - Percentage of Aboriginal deaths where agencies (e.g. police watch-houses, prisons or hospitals) failed to follow all of their own procedures. [7]

1987: The Royal Commission starts work

In 1987 the government led by Bob Hawke decided something must be done about a rising number of complaints that Aboriginal people were dying in suspicious circumstances in police cells.

It announced a Royal Commission (a major government public inquiry into an issue) into Aboriginal deaths in custody on 10 August 1987 in response to a growing public concern that such deaths were too common and poorly explained.

Hearings began in 1988. The commission initially set out to examine 44 specific cases but that eventually grew to 99, with 32 in Western Australia, 27 in Queensland, 21 in South Australia and the Northern Territory and 19 across NSW, Victoria and Tasmania [8].

The Commission submitted its final report in April 1991. All up, the commission cost about $40 million, with another $400 million spent on implement of its recommendations [8].

To monitor deaths in custody, the Australian Institute of Criminology established a national deaths in custody program which should publish an annual report.

A decade ago, the program was delivering its reports within days of the close of the reporting period - the 2003, 2004 and 2005 reports were delivered within one month. Then, without explanation, each of the next 3 reports took between 16 months and 2 years to appear. The 2009-11 report has been almost 3½ years in the making [9].

[The deaths in custody report] paints a horrific portrait of the state of indigenous criminal justice.

— Inga Ting, journalist, Sydney Morning Herald [9]

I am constantly stunned when many senators tell me that they are not aware of Australia's death in custody record.

— Gerry Georgatos, Human Rights Alliance, Perth [10]

Aboriginal Australians have learnt to fear for the lives of family members who end up in police cells or jail.

— The Saturday Paper [11]

Findings of the commission

The Royal Commission examined the deaths of 99 people who had died in custody between 1 January 1980 and 31 May 1989. It looked into both the causes of the deaths and the prevention of future deaths and tried to answer the question: Why are so many Indigenous people in custody? Why were they treated that way?

Some of the Commission's findings were: [12]

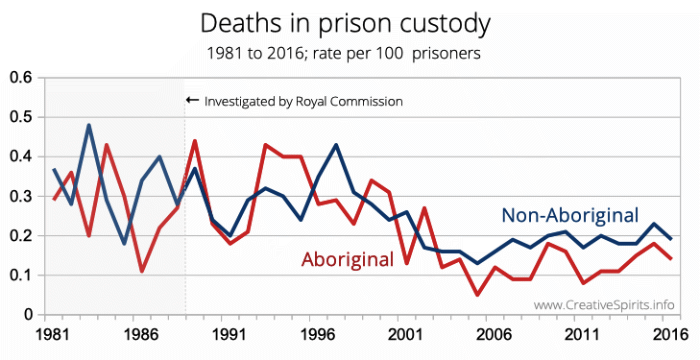

- Aboriginal people do not die at a higher rate than non-Aboriginal people in custody.

- The rate at which Aboriginal people are taken into custody is "overwhelmingly different".

The first finding might sound counter-intuitive at first, especially when putting it into context with data published elsewhere that shows much higher Aboriginal death rates for the same period. As with most statistics, we have to look at how the rates are calculated.

The Royal Commission calculated the death rate relative to the number of prisoners. This makes sense as it wanted to know if more Aboriginal prisoners die in custody than non-Aboriginal prisoners. The following graph shows this rate over time.

Other publications might show the rate per 100,000 of the general or Aboriginal population which will give very different results. Because Aboriginal people are over-represented in prison but a minority in the general population their death rate is much higher than that of non-Aboriginal prisoners.

While Indigenous people are not more likely to die in custody than non-Indigenous people, they remain significantly over-represented in all forms of custody.

— Adam Tomison, director, Australian Institute of Criminology [3]

Investigating the deaths in NSW, Victoria and Tasmania the commission found that 13 of the 18 people who died in custody may have survived had custodial authorities not been negligent, uncaring or had followed procedures adequately. The other 5 deaths might also have been avoidable on the grounds that these people may not have needed to be in custody at all. [14]

The commission's recommendations

The conclusion was that too many Aboriginal people are in custody too often. In its report the commission made 339 recommendations, for example

87. Arrest people only when no other way exists for dealing with a problem.

92.Imprisonment should be utilised only as a sanction of last resort.

161. Police and prison officers should seek medical attention immediately if any doubt arises as to a detainee's condition.

339. Initiate a formal process of reconciliation between Aboriginal people and the wider community.

The last recommendation led to the establishment of the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation.

For five years after the royal commission's final report, action on its recommendations was regularly monitored – but never after. If its recommendations had been followed, most of the more than 400 deaths in the years since could have been prevented, experts believe. [15]

One of the fundamental lessons of the royal commission was that Aboriginal people die in custody too often because they’re in custody too often and we need to stop locking up people for minor offences, particularly things like public drinking.

— Jonathon Hunyor, lawyer [11]

Who died in custody?

The National Archives of Australia have a list of names of persons who died between 1980 and 1989 and whose deaths were investigated by the Royal Commission.

Guardian Australia, in its Deaths Inside project, created a list of every known Aboriginal death in custody in Australia from 2008 to 2018. Filters allow a very detailed investigation of the data.

Aboriginal prison rates soar despite recommendations

At the time of the commission's final report in 1991, Aboriginal people were 8 times more likely to be imprisoned than non-Aboriginal people. A decade after the report was handed down they were 10 times more likely to be imprisoned.

In the 2010s, they were 15 times more likely. In Western Australia, which has the highest Aboriginal imprisonment rate in the country, Aboriginal people are close to 20 times more likely to be jailed than non-Aboriginal people [9].

Between 2003 and 2013, the Aboriginal rate of incarceration has soared 11 times faster than the non-Aboriginal rate. Prison rates for Aboriginal women have increased by a third between 2002 and 2007, and the number of Aboriginal men by one-fifth [17], while police custodial rates remain as high as before.

In 2009, the proportion of Aboriginal prisoners had almost doubled in the 20 years since the commission delivered its recommendations [9].

In 2013, the Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) found Aboriginal deaths in prisons had spiked over the 5 preceding years, despite deaths in custody for non-Aboriginal prisoners remaining stable. It found most deaths were caused by heart conditions and other medical problems, though self-harm remained high [18].

As if the royal commission never existed, the Northern Territory in December 2014 introduced 'paperless arrest laws'. Thought to free police from paperwork, the laws can be triggered by offences including swearing, drinking in public, making too much noise or having an untidy front yard. Previously these infractions merited only small on-the-spot fines. Of the 2,000 people who have been detained via paperless arrests, almost 80% are Aboriginal. In November 2015 the High Court of Australia ruled that paperless arrest laws were valid. [11]

There have been 340 Aboriginal deaths in custody since the end of the royal commission. Most could have been prevented if the [commission's] recommendations were all implemented.

— Peter Boyle from Australia's Green Left Weekly newspaper, in 2014 [18]

Community impact: "Families are destroyed by this cruelty"

When family members go to prison, families and communities are affected by the loss of parents, role models, childcare and family income.

The Indigenous Social Justice Association is fighting since many years for the rights of families whose loved ones died in police custody.

Their president, Ray Jackson, describes what these families have to go through:

"One cannot begin to explain what death-in-custody families suffer. In fact they suffer twice. firstly for their tragic loss but also by the continued indifference to the law of the land that states that the guilty must be held accountable. For over 450+ families this pain, this trauma eats at them everyday of their lives. Families are destroyed by this cruelty and white power indifference. The horror, the crimes against the families continue unabated." [19]

Governments fail to follow recommendations

These high prison rates come to no surprise.

A 1996 examination of 96 Aboriginal deaths in custody since the royal commission offered a dismal assessment of progress. It found that every state and territory had claimed implementation of recommendation 161. Yet this continued to be "a serious problem" in numerous deaths. [20]

Equally, every state and territory claimed that the principle of imprisonment as a last resort had been, or was in the process of, being implemented, but this wasn't entirely so.

A survey of the Australian Indigenous Law Review in 2009 showed that Australia's states still had only acted on a fraction of the commission's recommendations.

Victoria had acted on 27%, NSW on 48%, Tasmania on 41%, South Australia 52% and Western Australia 50%. Besides the Australian Capital Territory, the Northern Territory was the most adherent to recommendations because mandatory reporting is in place in the NT [21].

Six years later things hadn't improved much. A 2015 report by law firm Clayton Utz found that the bulk of the commission’s 339 recommendations remained unimplemented or only partially implemented. [22]

Worse, the Northern Territory government in 2014 introduced 'paperless arrest' laws, which allows officers to jail a person with no warrant and no charge for 4 hours.

"An arrested Aboriginal person has to run the gauntlet of first being in police custody then being placed in custodial transport, then being incarcerated in a prison," explains Aboriginal elder and leader of the Euahlayi tribe, Michael Anderson [23]. "At each stage we now have records that indicate that all three stages have increased their statistics of Aboriginal deaths since the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody."

When using the statistics, it is important that Aboriginal deaths are placed in the context of the number of people in prison. "At the heart of the problem is the over-representation of indigenous persons at every stage of the criminal justice system," concluded a report by the Australian Institute of Criminology in 2013 [24].

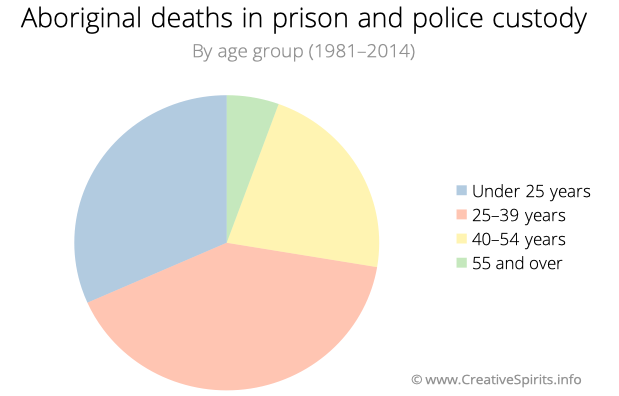

Aboriginal prisoners also die at younger ages from natural causes [24], reflecting the poorer health conditions and lower life expectancy of Aboriginal people.

Police have a duty of care no matter what [offenders] have done.

— 'Recruits', episode 11 on Australia's Channel 10

Homework: Examine causes for high death in custody rates

Why do you think there are so many Aboriginal deaths in custody?

To answer this question, examine the relationship between Aboriginal people and police and why they get arrested and put into prison. Which health issues contribute to the high rate?

Compare your findings with experiences of non-Aboriginal people.

Death in custody case studies

Aboriginal deaths in custody happened before the commission was formed and still happen today.

The death of Lloyd Boney, found hanging in a police cell in Brewarrina, NSW, in August 1987 is regarded as the catalyst for the royal commission [8].

The deaths of John Pat and Eddie Murray are two more examples. One of the more recent cases is the death of Doomadgee Mulrunji in 2004 after a senior police officer 'fell' on him.

Story: Death of John Pat (aged 16)

John Pat was just 16 years old when he got involved in a fight outside the Victoria Hotel in September 1983 in Roebourne, northern Western Australia. Off-duty police allegedly had assaulted Aboriginal people who in turn fought back, sparking the brawl.

According to witnesses, John Pat was struck in the face by a policeman and fell backward, striking his head hard on the roadway. One of the off-duty police went over to Pat and kicked him in the head.

Pat was then allegedly dragged to a waiting police van, kicked in the face, and thrown in 'like a dead kangaroo' [25]. He and other Aboriginal people were driven to Roebourne police station.

While some of the assaulted Aboriginal people spent up to a week in hospital recovering from the injuries inflicted on them by police, John Pat died a little over an hour after he was locked up.

A subsequent autopsy revealed a fractured skull, haemorrhage and swelling as well as bruising and tearing, of the brain. Pat had sustained a number of massive blows to the head. One bruise at the back of his head was the size of the palm of one's hand.

Police seem to respond more vigorously to public drunkenness by Aboriginal people than to domestic violence in white society. In 1983 Roebourne had eight officers and two police aides while the nearby 'white' town of Wickham had half as many police for twice the population [25].

In court an all-white jury heard the five police officers denying the acts of violence they were accused of, and that any actions on their part were done in 'self-defence' despite evidence of blood on police officer's boots.

On the same day the jury found all police not guilty. No charges were ever laid.

Charges were laid against some of the Aboriginal people, and they were subsequently fined for assault, resisting arrest or hindering police.

30 years later, in September 2013, the West Australian State Parliament formally apologised to the family of John Pat for his death.

The death in custody of John Pat bears great parallels to the case of Mulrunji Doomadgee on Palm Island in 2004 who died hours after he had been put in prison for public drunkenness.

We have to get rid of racist cops. I don't want to dwell on the past, but I have grown up bitter.

— Ben Taylor, Aboriginal elder, Perth [26]

John Pat by Jack Davis

Write of life / the pious said forget the past / the past is dead. But all I see / in front of me is a concrete floor / a cell door / and John Pat. Agh! tear out the page / forget his age thin skull they cried / that's why he died! But I can't forget / the silhouette of a concrete floor / a cell door / and John Pat. The end product / of Guddia law is a viaduct / for fang and claw, and a place to dwell / like Roebourne's hell of a concrete floor / a cell door / and John Pat. He's there - where? there in their minds now / deep within, there to prance / a sidelong glance / a silly grin to remind them all / of a Guddia wall a concrete floor / a cell door / and John Pat.

'Guddia' is a Kimberley (north Australian) term for the white man. The poem was also published in Jack Davis' book 'John Pat and Other Poems'.

Each year on September 28, John Pat Day, people hold memorial services or march in protest.

In his 2007 album Journey, Archie Roach included a song about John Pat.

Story: Death of Eddie Murray (aged 21)

Eddie Murray was 21 when he was last arrested. On June 21, 1981 he was drinking under a tree with his cousin and some friends.

He was arrested at 1.45am, taken to Wee Waa police station (about 400 kms north-east of Sydney), and held under the Intoxicated Persons Act. Within an hour he was dead, and his family have consistently attempted to find the cause of his death.

At the inquest the police claimed he had killed himself by hanging, even though they agreed under cross examination that he was "so drunk he couldn't scratch himself". Yet according to them, Eddie had managed to tear a strip off a thick prison blanket, deftly fold it, thread it through the bars of the window, tie two knots, fashion a noose and hang himself without his feet leaving the ground.

Later the police were found to have lied under oath. The coroner ruled that Eddie had died "at the hands of person or persons unknown" and strongly criticised the police. No-one was charged with Eddie's murder, a fact that left his parents Arthur and Leila deeply unsatisfied.

The Murrays initiated an exhumation of Eddie's remains in 1997 which revealed injuries undisclosed at the original post mortem and during the Royal Commission, and in 2000 the matter was referred to the NSW Police Integrity Commission for further investigation.

Resource: Eddie's Country

cover.jpg)

In 2006 Simon Luckhurst launched his book Eddie's Country, a detailed history of the complex social, historical and legal issues experienced by members of the Murray family:

"It attempts an unbiased and comprehensive exploration of the Eddie Murray case, which incorporates a socio-political context as well as a personal one. For the first time all the available evidence on the case has been brought together, and the result is both revealing and moving." [27]

Story: Death in 42-degree heat

On the night of 25 January 2008 Mr Ward was arrested for a traffic offence in Laverton, about 900km north-east of Perth [28]. A Justice of the Peace refused him bail so that the next day he was to be transported to Kalgoorlie, 360km south, for a scheduled court appearance the following week.

He was placed in the steel cell of an ageing prison van in 42-degree heat and only given a 600ml bottle of water. The two prison officers driving the van did not make any comfort breaks or checks on Mr Ward.

It wasn't until they heard a thump that they stopped and checked, discovering Mr Ward had collapsed in the back of the van. He was taken to Kalgoorlie hospital but all efforts to revive him failed. He had died of heatstroke.

An inquest into Mr Ward's death-in-custody case found that the two prison officers, the prisoner transport company and the Western Australian Department of Corrective Services were collectively responsible for his death. [29]

"The doctor who opened the door of the van to extract Mr Ward told the inquest that it felt like a blast from a furnace as the air escaped from the tiny steel cell pod."

Evidence indicated that Aboriginal Elder Mr Ward had suffered third degree burns to his upper torso after falling onto the hot surface of the steel cell.

The department had been warned many times that the vehicles used to transport prisoners in remote regions were "a grave danger" to any prisoner.

More than two years later the Director of Public Prosecutions decided not to lay charges against the two security guards [30], noting that he could not determine if they had colluded when giving evidence.

On July 29, 2010 the family of Mr Ward received one of the largest ex-gratia payments ever made in Australia when the West Australian government approved $3.2 million, recognising a "terrible wrong" [31]. The money only covers lost wages of Mr Ward and does not compensate for his inhumane treatment.

Both the Department of Corrective Services and the prisoner transport company G4S pleaded guilty [32]. However, no-one has been charged with any offence in relation to, and there will be no prosecutions resulting from, Mr Ward's death [33].

A question which is raised by the case is how a society, which would like to think of itself as being civilised, could allow a human being to be transported in such circumstances.

— Alistair Hope, coroner [29]

Resources

Deaths in Custody Watch Committee WA

The Deaths in Custody Watch Committee in Western Australia was set up by a coalition of concerned parties in 1993. Its specific aim is to monitor and work to ensure the effective implementation of the Royal Commission Into Aboriginal Deaths In Custody.

[Mulrunji's] death and all deaths in custody have had a profound impact. This man carried within him songs, stories, dreaming that belonged to his country, and all that was obliterated when he was killed on that floor.

— Sam Watson Snr, Brisbane Aboriginal community leader [34]

Australian Institute of Criminology

The AIC is the government department that supplies the Australian Bureau of Statistics with its data about deaths in custody.

To get the government-flavoured perspective, browse its collection of articles on Deaths in prison custody which, among many other statistics, also include Aboriginal deaths in custody by state or territory.

Homework: Your day at court

Following are comments made by Commissioner Judge Hal Wootten, who was part of the Royal Commission, in 2012: [35]

“The Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody was set up very hastily… We ended up being set up to investigate the wrong question… The question we were set to investigate was really, were police and prison officers killing Aboriginals, and the real question was why were so many Aboriginal people being put in jail?”

Questions

- What would be a likely answer to the two questions Commissioner Wootten mentions?

- Why do you think the Commission investigated the wrong question?

- Is the "real question" still relevant today? Why or why not?